Adaptation

Introduction

How a person adapts and is engaged is important information measured by the adaptive profile. This information has profound implications for understanding a person’s efficacy and performance, with remedies that can be found in the person’s Natural profile, how they understand their potential and motivation, connect with others, their job, and the environment.

Generalities

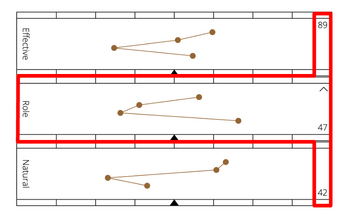

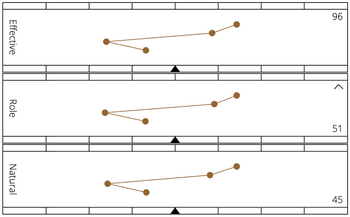

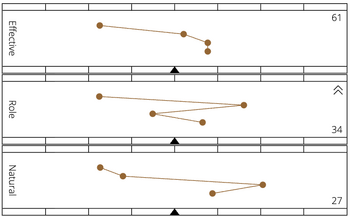

The Role profile—the profile in the middle of the adaptive profile, circled in red on the right—measures how people more or less adapt to the environment in a way that’s engaging or not. The more different the Role profile is from the Natural, the greater the perceived need for adaptation. Consequently, the Effective behavior—the profile on top, the behaviors people most probably see—will be different. The arrows and numbers on the right indicate how the person feels engaged or disengaged in their environment.

Conceptualization

The conceptualization of the Role concurs with the dynamic model of personality elaborated by Mischel and Shoda[1] Adaptation can also be approached by the observations of organizations[2] and society[3]. In sociology, the Role is analyzed by symbolic interactionism and functional perspectives.

- With symbolic interactionism[4], the individual interacts with the environment through their cognitive, affective, and symbolic faculties. They adapt their natural behaviors to the environment as they perceive it.

- From the functionalist perspective, a person's social role influences their mode of action. What is expected of the person and how they integrate it determines their social behavior[5]. The Role graph measures the behavior that the person perceives to act out. This behavior may differ from what is expected by the environment.

The perceived adaptation showing in the Role profile can be circumstantial, reflecting temporary efforts, or structural when the required efforts are prolonged. Adaptation results from the environment's or a person's insistence on adapting behaviors over time. The following aspects of the adaptation are further described below:

- Flow and personal efficacy when the three profiles have shapes close to each other,

- Adaptation when the shapes of the Natural and Role profiles are different, and

- Engagement and disengagement, where the arrows to the right of the Role profile point up or down.

Flow and Personal Efficacy

In the examples below, the three graphs are aligned. The perceived role is in phase with the natural behaviors. Consequently, the behaviors of the Effective are aligned too. In these situations, the person adopts behaviors that are in sync with their natural way of behaving; the person is in flow, a state of effortless immersion in an activity, with a feeling of energized focus and full involvement in the current process. [6].

The concept of adaptation, as it is evidenced in the Role profile, concurs with the observations of self-efficacy. Self-efficacy refers to a person mastering and controlling their environment[7] and also mastering their belief about their own skills[8]. Self-efficacy, which is considered a stable disposition and highly resistant to change[9] is associated with more job satisfaction through its impact on self-evaluation[10], less burnout[11] and higher performance[12].

Adaptation

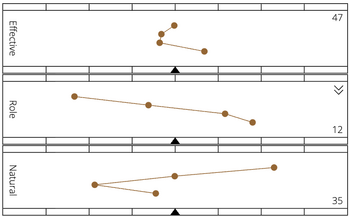

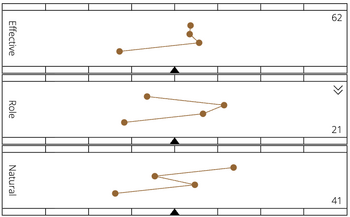

The more different the shapes of the Natural and Role profiles are, the greater the pressure from the person or from the environment to adapt. Significant discrepancies between the Natural and the Role come along with what has been described in the literature as emotional fatigue, a feeling of depersonalization, and less accomplishment[13], abusive, aggressive behaviors[14] or psychological pressures of depression[15], coming for some with a lack of sleep and gastric problems[16].

A wide profile with an inverted Role, as in the figure below, creates frustration and burnout and will cause the person to disengage or leave the position. These situations come with a reduction in self-confidence, well-being, and productivity.

Engagement and Disengagement

A difference in response levels indicated by the three numbers on the right of the profiles) between the Natural and the Role reflects whether the environment stimulates the person, and they consequently feel engaged (arrows pointing up) or the opposite, disengaged (arrows pointing down). This measure comes from the different responses given to the two questions of the GRI survey about the environment and oneself.

The arrows pointing up indicate stimulation, engagement, involvement, and commitment. Conversely, the arrows pointing down indicate demotivation, disengagement, and lack of productivity. The figure below shows examples of very low and very high engagement.

This dimension of engagement can be approached by the opposite of Self-efficacy[17] or negative affectivity when the engagement is low and is combined with little adaptation.

When a single arrow points down, this reflects the person’s low engagement. With two arrows, it reflects high dissatisfaction[18], frustration[19], or an intention to leave work[20]. They may be associated with a lack of environmental support[21].

Practical Implications

A state of flow with synchronicity between the three profiles of the Natural, Role, and Effective is ideal. Nonetheless, high adaptation, as it is measured with the Role profile, is inevitable from time to time. It may happen for a variety of reasons inherent to the person and their environment. At work, it may be required by all parties. Disengagement that results from a disconnect between a person’s interest and motivation and what the environment can offer may happen from time to time as well.

A feedback session on the adaptive profile is often the starting point for effective adaptation and reengagement. The session allows individuals to become aware of their Natural way to act, think, and feel, and to be more effective in the adaptation process. The Natural profile offers insight into how the person perceives adaptation and disengagement, and how these can be addressed, including with the environment’s support. A position’s profile, something we refer to at GRI as the Position Behavior Indicator (PBI), is typically discussed between managers at the company to help understand the needed adaptation and identify solutions with the person.

Notes

- ↑ Mischel, W., Shoda Y. (1995). A Cognitive-Affective System Theory of Personality : Reconceptualizing Situations, Dispositions, Dynamics, and Invariance in Personality Structure. Vol. 102, No. 2, p. 248-268.

Mischel, W., Shoda Y., Ayduc, O. (2008). Introduction to Personality. Toward an Integrative Science of the Person. John Wiley & Sons. - ↑ Likert, R. (1967). The Human Organisation. Its management and value. New York: McGraw Hill.

- ↑ Riesman, D., Glazer, N., Denney, R. (1950). The Lonely Crowd: A study of the changing of American Character. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- ↑ Mead, G. H. (1934). From the standpoint of a behaviorist. University of Chicago Press.

- ↑ Parsons T. (1951). The Social System. New York: The Free Press.

- ↑ Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly (1990). Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. Harper Perennial Modern Classics

- ↑ Bandura A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- ↑ Eden, D., Kinnar, J. (1991). Modeling galatea: Boosting self-efficacy to increase volunteering. Journal of Applied Psychology, 76, 770-780.

Judge, T. A., Bono, J. E., Locke, E. A. (2000). Personality and Job satisfaction: The mediating role of job characteristics, Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 237-249. - ↑ Perrewé P. L., Spector P. E. (2002). Personality Research in the Organizational Sciences, Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management, vol. 21, pp 1-63

- ↑ Ibid, Judge, Bono & Locke, 2000.

- ↑ Ibid, Perrewé P. L., Spector P. E. (2002)

- ↑ Quinn, R. E. (2000). Change the world. How ordinary people can achieve extraordinary results. San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

- ↑ Zellars, K. L., Perrewé, P. L., Hochwarter, W. A. (1999). Mitigating burnout among high-NA employees in health care: What can organizations do? Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 29, 2250-2271.

- ↑ Fox, S., Spector, P. E., Miles, D. (2001). Counterproductive work behavior (CWB) in response to job stressors and organizational justice: Some mediator and moderator tests for autonomy and emotions. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 59, 1-19.

- ↑ Fortunado, V. J., Jex, S. M., Heinish, D. A. (1999). An examination of the discriminant validity of Strain-Free Negative Affectivity scale. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 72, 503-522.

- ↑ Parkes, K. R. (1999). Shiftwork, job type, and the work environment as joint predictors of health-related outcomes. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 4, 256-268.

- ↑ Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Freeman

- ↑ Cavanaugh, M. A., Boswell, W. R., Roehling, M. V., Boudreau, J. W. (2000). An empirical examination of self-reported work stress among U.S. managers. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 65-74.

De Jonge, J., Dormann, C., Janssen, P. P. M., Dollard, M. F., Landeweerd, J. A., Nijhuis, F. J. N. (2001). Testing reciprocal relationships between job characteristics and psychological well being: Cross-lagged structural equation model. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 74, 29-46. - ↑ Chen, P. Y., Spector, P. E. (1991). Negative affectivity as the underlying cause of correlations between stressors and strains. Journal of Applied Psychology, 76, 398-407.

- ↑ Van Katwyk, P. T., Fox, S., Spector, P. E., Kelloway, E. K. (2000). Using the Job-related Affective Well-being Scale (JAWS). To investigate affective responses to work stressors. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5, 219-230.

- ↑ Moyle, P. (1995). The role of negative affectivity in the stress process: Tests of alternative models. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 16, 647-688.