Cybernetic Perspective

Introduction

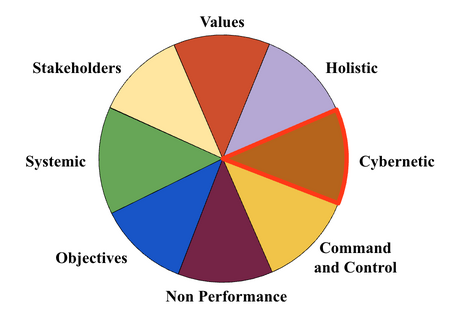

While traditional management systems rely on a top-down, command-and-control hierarchy, cybernetic models view an organization as a self-regulating system that uses feedback to maintain its goals. Performance measurement is seen as an important component of cybernetic models that include goal setting and predictive models to facilitate decisions of alternative actions.

Generalities

The origin of the cybernetic models goes back to the end of the 1940s and 1970s with the work of Robert Wiener[1], then Stanford Beer and his Viable System Model (VSM)[2]. With both traditional management control systems and cybernetic models, data plays an important role, but with cybernetic models, data is intended to be used to drive continuous, adaptive change, whereas in traditional systems, it is used to enforce standards. In the cybernetic models, measures involve both some aspects of control and others of communication and behavior[3].

In summary, the cybernetic models include the following four considerations:

- Feedback loops: Output information from the system is continuously fed back as input, allowing the organization to self-regulate and adjust course.

- Adaptation: The organization's ability to adapt internally and externally to its environment is critical.

- Complex systems: an organization is a complex, interconnected whole, as opposed to being a collection of isolated, independent parts.

- Decentralized control: Although a central command exists with a cybernetic model, the organization’s units have the autonomy to respond quickly to local changes, as they are capable of making the best-informed decisions based on the most current information.

Cybernetic models attempt to rigorously establish processes for planning, comparing, and evaluating[4] by considering two distinct sets of measures: Those defined by the objectives and those required by the predictive models. Traditionally, control systems have emphasized goal-oriented measures[5]. Performance measurement became associated with negative feedback based on the detection of the gaps between the planned objectives and the actual measures of the outcome[6].

Critics of the Cybernetic Model

Although ERP (Enterprise Resource Planning) systems have considerably eased the way data is collected and analyzed, particularly in large organizations, one of the challenges of the cybernetic model remains its difficulty in comparing performance data to quantifiable and unambiguous standards, in a context that’s constantly changing. Cybernetic systems will potentially miss crucial information, with no capacity to think and act on something already in someone’s mind, but that the systems cannot know yet.

From the cybernetic perspective, performance measurement is essentially associated with controlling the achievement of organizational objectives and the implementation of the strategy. Performance measures are implicitly linked to the notion of diagnostic and control systems[7], or formal feedback systems used to control what the organization produces and to correct deviations from a predefined performance standard[8].

Financial information is associated with traditional planning and control cycles[9]. In traditional management control systems, resources are totally focused on the management of accounting information[10]. Financial measures express the results of decisions in a comparable unit of measurement. They summarize the arbitration cost between resources as well as the cost of unused capacities[11]. Additionally, they are the measure for contractual relations and financial markets[12].

Traditional measurement systems encourage conservatism and a do-it-yourself attitude. Measures such as ROI (Return On Investment) discourage managers from innovating, investing in market share, or developing sources of competitive advantage[13]. They encourage compliance[14]. Moreover, the flexibility and creativity of strategic planning can be ruined by formal control systems[15].

Control systems create a climate that can act against the success of a strategic implementation and its formulation processes. Management control systems can promote or inhibit innovation depending on how they are defined[16]. The construction of a management information and control system requires several decisions concerning the choice of information measured, omitted, and reported. A system that filters inconsistently promotes a fictional satisfaction and clarity that will confirm conventional reasoning. The perception of a manager is limited to the information available[17].

The cybernetic vision's emphasis on financial information has led to errors in calculating production costs, to inadequate control of information, and to the absence of long-term performance measures[18]. Information prepared for external use is inadequate and insufficient for internal use[19].

Limiting Factors

The cybernetic models work well for the industrial age, but they are out of step by reducing human behavior to a mechanistic input-output loop, and with the talents and skills of knowledge workers that companies are trying to develop[20]. Several factors have been summarized that show the limit of the cybernetic process to respond to change[21]:

- Lack of resources to obtain information in quantity and quality

- Institutionalization of past successes, which inhibits the perception of necessary transformations

- Degree of centralization and concentration of specialists

- Elite values

- Time taken by the hierarchy to find the correct answers and respond.

The limitations of the cybernetic approach come up comparably in other studies[22]:

- Too historical and "looking back"

- Lacks predictive ability to explain future performance

- The reward of behaviors is short-term or on incorrect terms

- Lack of operationality

- Incapable of sending signals for change early enough

- Too aggregated and summarized to be able to guide managerial action

- Reflects functional processes instead of cross-functional processes

- Gives inappropriate guidance for assessing intangible values

Human Limiting Factor

The cybernetic model can be seen as a better version of the traditional model, which supports top-down hierarchical decisions and the command-and-control model. It gives more space to individual communication, adaptation, feedback, and autonomy.

Similarly to the control and command system and as we evidence with GRI's measures, forcing a system that’s fundamentally Low 2, High 4[23], on people who are not and exhibit opposite profiles, will create frustration, result in disengagement over time, and actions that will be counterproductive for the organization. The same limitations came with the competency models that emerged at about the same period as cybernetics and failed to differentiate competencies from aspects of behaviors or mindsets that cannot be developed at will or through traditional technical training.

Additionally, roles, including leadership roles, may considerably vary depending on situations—think about sales or client service versus accounting—and call for adaptations that, over time, may be beyond someone’s comfort zone and unique capabilities to perform.

Over time, profiles that we measure at GRI with a high 1 or low 4, who can bring and lead radical innovation, will sooner or later feel constrained and leave the organization. Very and extremely High 2s, if misunderstood, will similarly prefer to bring their social skills outside the organization. Low 2s immersed in high 2 roles will disengage over time, etc. The cases are varied and numerous that cannot be envisioned, accounted for, or managed with the cybernetic models, and can easily create inefficiency and underperformance.

References

- ↑ Wiener, N. (1948). Cybernetics: Or, Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine. John Wiley & Sons.

- ↑ Beer, S. (1979). The heart of enterprise: The managerial cybernetics of organization. Wiley.

- ↑ Flamholtz, E. G., Das, T. K., Tsui, A. S. (1985). Toward an integrative framework of organizational control. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 10, 1, pp. 35-50.

- ↑ Merchant, K. A., Simons, R. (1986). Research and control in complex organizations: an overview. Journal of Accounting Literature, 5, pp. 183-203.

The meanings of "objective" and "goal" may sometimes differ. See a note on their differences here. - ↑ Otley, D. T., Berry, A; J. (1980). Control, organization and accounting. Accounting, Organization and Society, 5, 2, pp. 231-244.

- ↑ Hofstede, G. (1978). The poverty of management control philosophy. Management control philosophy, 3, 3, pp. 450-461.

- ↑ Simons, R. (1995). Levers of control: How managers use innovative control systems to drive strategic renewal. Boston, Harvard Business School Press.

- ↑ Ibid, Hofstede, 1978

- ↑ Nanni, A; J., Dixon, R., Vollmann, T. E. (1992). Integrated performance measurement: management accounting to support the new manufacturing realities. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 4, pp. 1-19.

- ↑ Johnson, H. T., Kaplan, R. (1987). Relevance lost: The rise and fall of management accounting. Boston, Harvard Business School Press.

- ↑ Epstein, M. J., Manzoni, J.-F. (1997). The balanced scorecard and tableau de bord: translating strategy into action. Management Accounting, August, pp. 28-36.

- ↑ Atkinson, A. A., Waterhouse, J. H., Wells, R. B. (1997). A stakeholder approach to strategic performance measurement. Sloan Management Review, Spring, pp. 25-37.

- ↑ Dent, J. F. (1990). Strategy, organisation and control: some possibilities for accounting research. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 15,1-2, pp. 3-25.

- ↑ Roberts J. (1990). Strategy and Accounting in a U.K. Conglomerate. Accounting, Organizations and Society 15, no. 1–2.

- ↑ Ibid, Flamholtz et al., 1985.

- ↑ Ibid, Dent, 1990.

- ↑ Ibid, Flamholtz et al., 1985.

- ↑ Ibid, Johnson, H. T., Kaplan, R., 1987.

- ↑ Ibid, Atkinson, and al., 1997.

- ↑ Kaplan, R. S., Norton, D. P. (1992). The balanced scorecard -Measures that drive performance. Harvard Business Review, January-February, pp. 71-79.

- ↑ Hage, J. (1980). Theories of transformation: form, process and transformation. New York, John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

- ↑ Ittner, C. D., Larcker, D. F. (2001). Assessing empirical research in managerial accounting: a value-based management perspective. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 32, pp. 349-410.

- ↑ | This terminology that relates to GRI profiles is introduced in this article