Holistic Perspective

Introduction

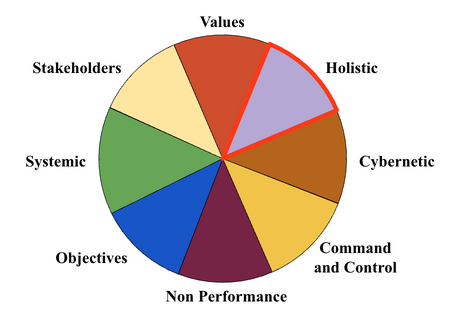

The holistic view of performance is a continuation of the cybernetic model, but differs significantly in its focus on the properties of the organization as a whole and emphasizes the relationships and interactions of its parts[1]. This article is on the performance measures used by holistic models, with an excerpt on Kaplan and Norton’s model.

Generalities

With the holistic model, performance measures are used to facilitate interactions[2], formulate and implement the strategy by revealing the connections between goals, strategy, with indicators of delay and progress[3], and subsequently to help communicate and operationalize the strategic priorities[4].

The holistic model includes the second-order feedback loop and control goal setting[5]. The second-order feedback loop involves the modification of goals, assumptions, and strategic plans following stakeholders’ learning experience[6]. With their ability to acquire, distribute, interpret, and memorize information, performance measures encourage organizational learning[7]. The role of performance measures evolves from being a simple component of the planning and monitoring cycle to an independent process that provides a steering function. While in the cybernetic model, the measures account for the distance toward a goal of the planning and control cycles, in the holistic model, the measures account for how the organization progresses in a strategic direction.

To stimulate learning and contribute to the formulation of strategies, measures of the holistic model focus attention on strategic priorities, create visibility within the organization to ensure coordination, drive action, and improve communication, which is considered essential for learning[8]. Measures are made available to leaders and managers to help them focus attention and effort toward critical uncertainties. Discussions, debates, action plans, ideas, and testing across the organization encourage learning and the emergence of new strategies and tactics.

Kaplan and Norton Model

Kaplan and Norton constructed the Balanced Scorecard, which incorporates the second-order feedback loop and, as such, can be viewed as supporting the holistic model. The system measures the achievement of the strategic plan's components. It functions as a management tool[9]. Its generic multi-dimensional chart aims to extend financial measures by including three non-financial dimensions related to the company's strategy:

- Customers,

- Internal processes, and

- Innovation, learning, and growth[10].

Critics report several weaknesses of the balanced scorecard, such as the absence of procedures to represent the relationship between means and ends, a neglected link with forms of reward, the establishment of information systems and feedback loops that are taken for granted, and the absence of guidelines for setting goals[11]. Some have raised concerns about the temporal dimensions, the relationships between measures, and the interdependence of dimensions[12]. Others have considered the approach incomplete, failing to highlight the contribution of employees, suppliers, and the community in general[13]. Norton and Kaplan themselves have noted the limits of the Balanced Scorecard:

- Unachievable strategy projects,

- Dissociation between strategy and objectives,

- Strategy unrelated to the allocation of resources,

- Solely tactical feedback or an absence of information on the execution and results of the strategy. There is no oversight on the implementation. Returns are only on financial indicators.

More specifically, Norton and Kaplan note the difficulty of objectifying performance measures on a human level. They talk about a lack of indicators[14]. Others have proposed a different approach to a pyramidal performance system[15]. The primary objective here is to link strategy and operations by translating top-down strategic objectives and bottom-up metrics. Objectives and measures are conveyed through four successive levels:

- Corporate vision,

- Business unit,

- Operational departments, and

- Work center.

On these four levels, financial and non-financial measures are used to formulate a strategy and implement it.

Other Critics

In the holistic model, non-financial measures can be problematic because their relationship with profits is not clear[16]. The capabilities of ERP (Enterprise Resource Planning) and HCM (Human Capital Management) systems will continue to increase their capabilities to collect information and provide dashboards to management, as supported by the holistic models. Those systems nevertheless do not decomplexify the nature of human behaviors and their relationship with performance. As with all types of measures, those of human behavior need to be adequately collected, understood, and used.

A study based on 23 companies demonstrated that although financial information is still very important, non-financial measures such as customer satisfaction, operational efficiency, employee performance, the environment, innovation, and change are valued by leaders[17]. These factors are incorporated into management reviews and serve to drive organizational change.

Multiple studies show that the use of non-financial measures has an impact on the economic performance of the company[18]. In a context where companies implement non-financial measures such as employee and customer satisfaction, quality, market share, productivity, innovation, etc., these measures are associated with:

- An innovation-oriented strategy,

- Quality-oriented strategy

- Length of product development cycle,

- Industry rule

- Financial strain

The relationship between non-financial and financial measures depends on whether the non-financial data match the characteristics of the organization[19]. Non-financial information is more suitable for lower-level managers who need direct feedback on operational activities, while financial considerations are more relevant for higher-level management[20].

In complex, competitive, and uncertain rather than stable markets, non-financial measures are described as more satisfactory than financial measures[21]. But the results of this study are tempered by studies that found no relationship between the four dimensions of Kaplan & Norton's balanced scorecard[22]. A reason might be that firms in competitive markets rely on multiple performance measures[23].

In the assessment of the organization's members' non-financial performance, engagement, TinyPulse, and satisfaction surveys are not without problems with regard to the practical use of the information collected. Once a state of non-performance is known, such as stress, the question remains how to prevent it in the future. The non-performance indicator should point to the means that will allow its prevention, control, and resolution in a future similar event.

The measures brought to the interactive control from a holistic perspective should serve as tools for managers and leaders to help focus attention, address or prevent issues, learn, and develop strategies on non-financial aspects, including social ones.

Human Limiting Factor

Holistic models can potentially account for how human beings make decisions and act in a multi-variate environment. That’s the information we collect at GRI and have seen being successfully used this way. The technology for integrating information within large enterprise systems and applications for management control is no longer a challenge.

However, more challenging is discerning the quality of information, whose nature is more abstract, and how the information is learned and used. The information about how people cope differently with norms, stress, autonomy, authority, reporting, decision making, creativity, communication, and more, all aspects that relate to people’s psychology, their style, preferences, values, motivation, behavior, emotions, or personality. This is an important piece of information that’s generally touched on during team-building exercises and coaching sessions. But it is not typically available through management control systems for helping managers recruit, strategise, and manage social dynamics.

As the means and actions engaged in a task become more important than only thinking about them, more objective information on a person’s behavior, emotions, and mindset that’s refined and can be shared becomes a critical element. Making this information available to managers can help them and their team be accountable for their collective efforts to perform, be appreciative of their differences, and adapt their behaviors to deliver the expected results.

In the holistic perspective, the adaptive profiles provide an understanding of humans’ thinking, feeling, and acting that happen when negotiating goals and reaching them. How people think, feel, and behave about the company’s culture, vision, mission, and objectives, how they define and refine them, is also part of the same information coming from the adaptive profiles.

By measuring the potential disconnect between a person’s behavior at flow and the organization's expectation, the adaptive profiles reveal the lack of engagement along with the rationale that accounts for its measure and the means for avoiding its future occurrence.

Notes

- ↑ Senge, P. M. (1990). The fifth discipline: The art and practice of the learning organization. Doubleday/Currency.

- ↑ Simons, R. (1990). The role of management control systems in creating competitive advantage: new perspectives. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 15 (1/2), pp. 127-143.

- ↑ Kaplan, R. S., Norton, D. P. (1992). The balanced scorecard -Measures that drive performance. Harvard Business Review, January-February, pp. 71-79.

Kaplan, R. S., & Norton, D. P. (1996). The balanced scorecard: Translating strategy into action. Harvard Business School Press. - ↑ Nanni, A; J., Dixon, R., Vollmann, T. E. (1992). Integrated performance measurement: management accounting to support the new manufacturing realities. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 4, pp. 1-19.

- ↑ Hofstede, G. (1981). Management control of public and not-for-profit activities. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 6, 3, pp. 193-211.

- ↑ Argyris, C, Schon, D. (1978). Organizational learning: A theory of action perspective. Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley.

- ↑ Kloot, L. (1997). Organizational learning and management control systems: responding to environmental change. Management Accounting Research, 8, pp. 47-73.

- ↑ Vitale, M. R., Mavrinac, S. C. (1995). How effective is your performance measurement system? Management Accounting, 77, 2, pp. 43-55.

- ↑ Kaplan, R. S., Norton, D. P. (2001). Transforming the balanced scorecard from performance measurement to strategic management Part I. Accounting Horizons, 15, 1, pp. 87-104.

- ↑ Ibid, Kaplan, R. S., & Norton, D. P., 1996.

- ↑ Ibid, Otley, D. (1999).

- ↑ Norreklit, H. (2000). The balance on the balanced scorecard – a critical analysis of some of its assumptions. Management Accounting Research, 11, pp. 65-88.

- ↑ Atkinson, A. A., Waterhouse, J. H., Wells, R. B. (1997). A stakeholder approach to strategic performance measurement. Sloan Management Review, Spring, pp. 25-37.

- ↑ Kaplan, R. S., Norton, D. P. (1998) The balanced Scorecard: Translating strategy into action.

- ↑ Lynch, R. L., Cross, K. F. (1991). Measure up – Yardsticks for continuous improvement. Cambridge, MA, Basil Blackwell.

- ↑ Fisher, J. (1992). Use of nonfinancial performance measures. Journal of Cost Management, Spring, pp.31-38.

- ↑ Lingle, J. H., Schiemann, W. A. (1996). From balanced scorecard to strategic gauges: is measurement worth it? Management review, March, pp. 56-61.

- ↑ Said, A. A., HassabElnaby, H. R., Wier, B. (2003). An Empirical Investigation of the Performance Consequences of Nonfinancial Measures. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 15, pp. 193-223.

Andersen, E., Fornell, C., Lehmann, D. (1994) Customer Satisfaction, market share, and profitability: Findings from Sweden. Journal of Marketing, July, pp. 53-66.

Banker, R. D., Potter, G., Srinivasan, D. (2000). An empirical investigation of an incentive plan that includes nonfinancial performance measures. The accounting review, 75, 1, pp. 65-92.

Foster, G., Gupta, M. (1997). The customer profitability implications of customer satisfaction. Working paper, Stanford University and Washington University. - ↑ Ibid, Said and al., 2003.

- ↑ Dixon, J. R., Nanni, A. J., Vollman, T. E. (1990). The new performance challenge – Measuring operations for world-class competition. Homewood, Illinois, Dow Jones-Irwin.

- ↑ Ibid, Dixon and al., 1990.

- ↑ Hoque, Z, Mia, L., Alam, M. (2001). Market competition, computer-aided manufacturing, and use of multiple performance measures: an empirical study. British Accounting Review, 33, 23-45.

- ↑ Ibid, Hoque and al., 2001.