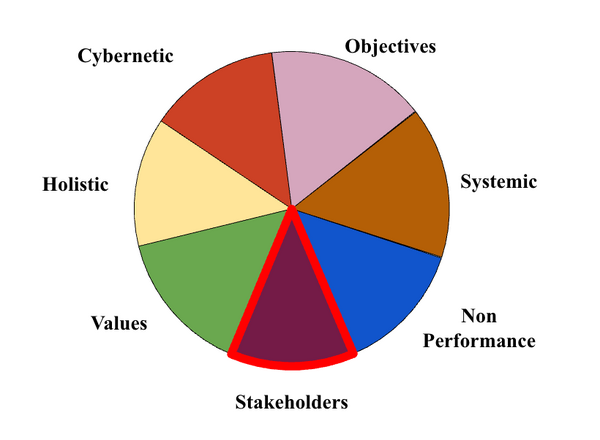

Performance by Stakeholders

Stakeholder performance models emphasize the expectations of individuals and interest groups that are either within or surrounding the organization[1]. With these models, the organization is viewed as a network of internal and external individuals negotiating a complex set of constraints and objectives[2].

After a quick review of what a stakeholder represents, this article examines the approaches that have positioned them at the core of an organization’s performance. The individual variables studied and the methods used have evolved over time. Here, a few models and variables commonly analyzed are summarized before focusing on stakeholders' diverse perspectives, values, and preferences.

Stakeholders

A stakeholder refers to any individual, group, or organization that has an interest in or is affected by the decisions, activities, and operations of the business. This includes employees, customers, suppliers, communities, regulators, shareholders, and more.

This is generally a two-way street: stakeholders can affect the organization, and the organization can affect them[3]. The concept of a stakeholder is not limited to a few specific groups. It includes a vast array of parties, which are often categorized in different ways.

Internal vs. External Stakeholders:

- Internal: Those with a direct, formal relationship with the organization. This includes employees, managers, and owners/shareholders.

- External: Those who are outside the organization but are still affected by or can affect its activities. This includes customers, suppliers, creditors, the local community, governments, and even competitors or the general public.

Primary vs. Secondary Stakeholders:

- Primary: Those who are directly and significantly impacted by the organization, often having a financial or contractual relationship. Examples include employees, customers, suppliers, and shareholders.

- Secondary: Those who are indirectly affected. Examples include community groups, environmental organizations, and government agencies.

The term "stakeholder" explicitly includes both groups of people (e.g., all employees, a specific community) and individuals who are members of those groups. The definition is inclusive and is meant to broaden the perspective of management beyond just the interests of shareholders to all parties who have a "stake" in the organization's success or failure.

Organizational Development Model

The Organizational Development (OD) model refers to any activity that can bring about changes in the organization, especially the mechanisms by which the organization’s members are considered. This model relates to work originating from the “T-Group” and sensitivity training from the National Training Laboratories[4]

The focus in this model is on the variables of internal stakeholders affecting organizational change, such as the open-mindedness of the people, the improvement of communication, the replacement of the organization’s members, other psychological variables, and social variables, rather than on performance metrics like profit or staff turnover.

The vision of performance implicit in this model includes the following points:

- Openness and responsiveness to change

- Optimistic vision of the organization’s members

- Accountability and confidence in members' efforts

- Members satisfaction

- Confrontation of conflicting situations rather than their avoidance

- Open and effective communication

- Sharing of values and a managerial strategy to support it

- Assistance to people in the organization to maintain their integrity and individuality

Most of the variables in the organizational development model relate to its people rather than the technological and material aspects of the organization. The following models are a few variations of this same organizational development model.

Likert Model

The Likert model emphasizes participation in decision-making and power sharing as key variables of a successful organization[5] The extent to which people can actually take part in the decisions that affect them influences the organization's ability to achieve its mission. System Four is regarded as the benchmark of a successful organization. The components highlighted in this system include the following:

- Leadership process

- Motivational practices

- Communication methods

- Interactions and influences among individuals

- How goals are set and accepted

- Degree of commitment throughout the organization to control processes

- Appropriateness of objectives and training levels

The main difference between this model and the organizational development model is that it places less emphasis on interpersonal and self-actualization variables.

Argyris Model

This Argyris model emphasizes the personality characteristics as it was understood in the 1950s and 60s, group dynamics, and interpersonal relationships[6]

Argyris examines how the organization influences individuals and how individuals behave in response. He points to personal factors that affect adaptation or growth within the organization, especially regarding responsibility, as causes of frustrations both within the organization and in trade unions.

The concept of feedback is highlighted as essential in individual and organizational learning processes[7].

Uncertainty Model

With this model, uncertainty is the main tool shaping power dynamics among people. Stakeholders’ logic and rationality often conflict with one another[8]

Stakeholders aim for minimal risk. Their compromises ensure the organization's survival, leading to rules that limit each stakeholder's power and direct their behavior. The rules established within the organization define this space of freedom between the rules. Within that space of freedom, stakeholders try to maximize their advantage in terms of gain or power.

Satisfaction Model

Chester Barnard is probably the first to have analyzed the aspects of satisfaction related to performance[9]. The performance (effectiveness) and efficiency of people and organizations are clearly distinguished. While performance and effectiveness are closely related and refer to the ability of individuals or organizations to achieve a desired goal, efficiency relates to the level of satisfaction or dissatisfaction with reaching the objective. Organizations’ objectives are important as long as their pursuit provides benefits for the organization’s internal stakeholders. These benefits for people, rather than the achievement of objectives—which may be valued differently by various stakeholders—are, in this model, the true measure of organizational performance. As long as stakeholders share similar expectations regarding organizational benefits, their interests can be combined into objectives that lead to their satisfaction. However, in the most common situation where their interests differ, the organization's performance depends on the unique expectations of each group or individual stakeholder. In this approach, external stakeholders are not taken into account.

Expectancy Model

The expectancy model considers individual performance by focusing on motivational aspects. Individuals choose one behavioral option over others. Unlike earlier theories that concentrate solely on needs (e.g., Maslow) or external stimuli, Vroom's model emphasizes the individual's perceptions and expectations about the relationship between effort, performance, and outcomes[10]

An individual's motivational force to exert effort towards a particular behavior is a product of three key psychological states:

- Expectancy: The individual's perception that exerting a given amount of effort will lead to a desired level of performance.

- Instrumentality: The individual's perception that achieving a certain level of performance will lead to specific outcomes or rewards.

- Valence: An individual places value on the potential outcomes or rewards.

According to this model, individuals who are motivated work harder and boost their performance level with their efforts, aligning with the rewards of their job. In return, organizations must be capable of understanding individuals and placing value on the outcomes that are useful for raising the individuals’ and the overall performance.

The expectation model highlights the subjective nature of motivation, emphasizing that a manager must understand an individual's unique perceptions and values to motivate them effectively.

The core idea is that an individual's motivational force (MF) to exert effort towards a particular behavior is a product of three key psychological states.

Stakeholders Variables

Stakeholders are subject to many more variables than the one mentioned above. Various models and approaches have focused on other variables, such as:

- Team building[11]

- Vulnerability[12]

- The consultation process[13]

- Coaching[14]

- Grit[15]

- Needs[16]

- Emotional intelligence[17]

- Psychological safety[18]

- Confrontation[19]

- Creativity[20]

- The managerial grid[21]

- Servant leadership[22]

- Transformational leadership[23]

All those above models and theories are variations of the same approach that emphasizes people and social variables, their relationship, relevance, and impact on stakeholders' performance and the performance of their organizations.

The number of stakeholder variables may, in fact, be unlimited. Aside from the one researched, others may be a more relevant focus for some organizations and their stakeholders depending on the company’s stage of life cycle (start-up, growth, maturity, decline), organizational industry and type (small, large, non-profit, etc.) and the stakholders perspectives (employees, clients, shareholders, government, etc.).

Although people and social variables are all critical at some point during the organization's development, they may also be less relevant and of second importance at other times, or only apply to a few stakeholders rather than the entire organization. Everyone agrees that psychological safety is generally important, but it was especially crucial during the pandemic years. It was more vital for some individuals and less so for others. While leadership is a significant factor to consider, its impact varies between managers and executives versus directors, entry-level employees, and other external stakeholders of the organization.

Stakeholders Perspectives

Identifying the stakeholders and their perspectives is critical but challenging when having to manage a company’s performance. Each stakeholder is more or less dependent on the organization. All stakeholders can hardly be assessed; the importance of internal or external stakeholders to the organization may be underestimated or ignored.

Organizations are fundamentally constrained by their external environment and their reliance on critical resources controlled by external stakeholders. As it has been emphasized with the Resource Dependency Theory (RDT)[24], one must look beyond an organization's internal structures and internal stakeholders' needs, particularly the flow of resources and the power dynamics that result from resource dependencies. Organizations are continually maneuvering in a complex web of relationships with internal and external stakeholders to secure their survival and maximize their autonomy.

A choice must always be made that will favor some stakeholders over others. Some research suggests that the most influential stakeholders should be identified. Others propose a way to calculate a satisfactory performance rather than maximizing that of any stakeholder, while acknowledging the practical difficulty of performing the calculation[25]. Understanding internal and external stakeholders' key variables, those that are vital for the organization’s growth or survival, becomes essential for the organization’s management and its leadership.

Stakeholders Preferences

A variety of contradictory individual preferences are pursued altogether in the same organization. The presence of contradictory preferences is a characteristic of loosely coupled systems. Not only are individually expressed preferences necessary for organizations to be efficient, manageable, and “benevolent,” but contradictions between these preferences exist that lead organizations to “grouch,” “clumsy,” and “strut” . Preferences between internal (shareholders) and external (customers) stakeholders are incompatible and cannot be satisfied. Finding compromises is necessary and inherent in all organizations. By pursuing several areas of activity simultaneously, being better in one area may have the implication of being less good in another. Conflicting preferences may exist at the same time because one area of activity may be dependent on another. When the domains are dependent, different strategies can be practiced such as:

- The "incrementalism" which consists of negotiating one set of preferences at the expense of others

- The "sufficiency" to meet all preferences, but up to a certain point

- The "sequencing" to alternate preferences

The confusion between stakeholder preferences has led research to differentiate what is accomplished legitimately from what is accomplished effectively; Or what is based on values: what is desirable, what is based on objectives: what is desired. A third approach differentiates between what is effective: doing things well, and what is efficient: doing the right things. These distinctions reinforce the idea that preferences can be contradictory with each other and within the organization.

The preferences expressed by stakeholders are frequently unrelated or negatively related to each other. Moreover, the criteria of stakeholders are hardly associated with the overall judgment of organizational effectiveness and performance.

Stakeholders Values

People have different values, interests, and unique ways of performing. As we evidence and measure with the adaptive profiles at GRI, the range of behavior expressed by stakeholders vastly varies. People may adapt on demand when they are interested and need to, and when their organization, through their jobs, requires them to do so. But they consistently function and behave differently.

Some people are at ease and in need of challenging situations that generally become conflicting, more than others, who are in need of team settings, cooperation, and prefer to stay away from conflicts. Those aspects that are at the crossroads of values, behavior, and personality are discussed in detail within the competing value framework.

For the organization to perform, stakeholders need to cooperate and be engaged, rather than disengaged, regardless of their natural tendencies. Some aspects, such as burnout, stress, disengagement, and negative rewards, can be minimized. While others, such as performance, well-being, efficiency, satisfaction, and positive reward, need to be maximized[26].

Expecting stakeholders to behave in only one way is unrealistic. What’s realistic, though, is 1) understanding the benefits of these “quiet” behavioral differences that develop silently through experience in the back of our minds, emotionally and cognitively, and 2) developing social intelligence to manage those differences effectively for the organization’s performance and, in turn, the performance of its stakeholders.

References

- ↑ Connoly, T., Colon E. M., Deutch, S. J. (1980). Organizational effectiveness: a multiple constituency approach. Academy of Management review, 5, 211-218.

Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach. Pitman. - ↑ Pennings, J. M., Goodman, P. S. (1977). Toward a Workable Framework. In P. S. Godman & J. M. Pennings (Eds.), New perspectives on organizational effectiveness. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Pp. 146-184.

- ↑ Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach. Pitman

- ↑ Bennis, W. G. (1979).. Organization Development: Its Nature, Origins, and Prospects. Reading, Mass: Addison-Wesley.

Bradford, L. P., Gibb, J. R., Benne, K. D. ( 1964). T-Group Theory and Laboratory Method. New York: John Wiley & Sons. - ↑ Likert, R. (1961). New Pattern of management. New York : McGraw-Hill.

Likert, R. (1967). The Human Organization. Its management and value. New York : McGraw Hill. . - ↑ Argyris C. (1957). Personality and Organization. The conflict between the System and the Individual. New York : Harper & Row.

Argyris C. (1964). Integrating the individual and the organisation. New York: Willey.

Argyris C. (2000). Knowledge for action. A Guide to Overcoming Barriers to Organizational Change, 1995.

Argyris C. (2000). Knowledge for action. A Guide to Overcoming Barriers to Organizational Change, 1995. - ↑ Argyris, C, Schon, D. (1978). Organizational learning: A theory of action perspective. Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley.

- ↑ Crozier, M., Friedberg, E. (1977). The actor and the system. Editions du Seuil.

- ↑ Barnard C. I. (1938). The functions of the Executive. Harvard University Press.

- ↑ Vroom, V. H. (1964) Work and motivation, New York, Wiley.

- ↑ French, W. L., Bell, C. H. (1978). Organization Development: behavioral science interventions for organization improvement. Englewood Cllffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Hackman, J. R. (2002). Leading Teams: Setting the Stage for Great Performances. Harvard Business School Press. - ↑ Brown, B. (2012). Daring Greatly: How the Courage to Be Vulnerable Transforms the Way We Live, Love, Parent, and Lead. Gotham Books.

- ↑ Schein, E. (1969) Process Consultation: Its Role in Organization Development. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publications.

- ↑ Whitmore, J. (2017). Coaching for Performance: GROWing Human Potential and Purpose (5th ed.). Nicholas Brealey Publishing.

Goldsmith, M., & Reiter, M. (2007). What Got You Here Won't Get You There: How Successful People Become Even More Successful. Hyperion. - ↑ Duckworth, A. (2016). Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance. Scribner.

- ↑ Maslow A. H. (1987). Motivation and Personality. Addison-Wesley Educational Publishers. Third edition. First published in 1954.

- ↑ Goleman, D. (1995). Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ. Bantam Books.

- ↑ Edmondson, A. C. (2018). The Fearless Organization: Creating Psychological Safety in the Workplace for Learning, Innovation, and Growth. John Wiley & Sons

- ↑ Beckhard, R. (1969). Organization Development: Strategies and Models. Addison-Wesley.

- ↑ Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1996). Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention. HarperCollins Publishers.

- ↑ Blake R.R., Mouton J.S. (1987). The 3rd dimension of management. Organization editions. Translated from: The Managerial Grid III: the key to leadership excellence, 1964.

- ↑ Greenleaf, R. K. (1970). The servant as leader. Robert K. Greenleaf Publishing Center.

- ↑ Bass B. M. (1990). Bass and Stogdill’s Handbook of Leadership : theory, research, and managerial application. New York : Free Press. First published in 1974.

- ↑ Pfeffer, J., Salancik, G. R. (2003). The external control of organizations. New York : Harper and Row. First published in 1978.

- ↑ Cameron, K. S., Whetten, D. A. (1983) Organizational effectiveness: One model or Several? Preface. Orlando: Academic Press.

- ↑ Turner, B. S. (1999). The Talcott Parsons Reader. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.