Adaptive Profile

Introduction

This article presents some key characteristics of adaptive profiles. Adaptive profiles are profiles like the one on the right. They represent a person’s performance in context. The measures are pivotal in GRI's approach to understanding how people behave, think and feel more objectively. The information is also used at a job and organizational level.

What the Adaptive Profile Tells

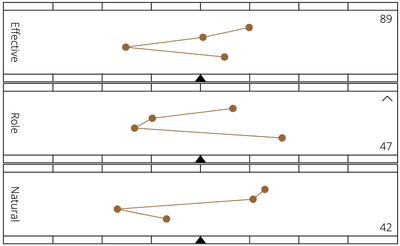

The adaptive profile tells about a person’s most natural way to perform (the Natural, the graph at the bottom), the perception to adapt to the environment (the Role, the graph in the middle) in a way that's engaging or not (the numbers and arrow on the right), and how the person effectively performs (Effective, the graph on the top).

The Effective on top represents behaviors that will most probably be observed. The Role cannot be observed since it's a perception, and the Natural may eventually be observed by knowing the person in different contexts over time. Importantly, the Natural profile indicates the person's behavior in flow.

Each graph shows four factors (the four small dots in each graph) and scales (the rectangles above and below the graphs) that indicate how intense and predictable a person is. An adaptive profile represents a person’s way to think, feel, act, and adapt. Depending on your experience of other measures and concepts, the measures can also be understood as a representation of a person’s mindset, preferences, and (behavioral) values. A profile has intensity: people express their behaviors more or less visibly and intensely. What is measured is not personality traits or types, although those concepts can be inferred from the adaptive profiles, but rather how people function.

Why Using Profiles?

Measures comparable to the GRI are usually represented in various formats, such as reports, histograms, scatter charts, or pies. The different formats are combined in reports.

The conciseness of the adaptive profiles has proven its advantage for efficiently learning, memorizing, and using the information on people and jobs whenever needed: What’s expected in the job that can be found in people? What energy does it take to adapt to the job or a situation? With the adaptive profiles, the comparisons and answers are immediate. Each of the four factors adds meaning to the three others. The four factors combine in the profile, bringing many nuances that would be impossible with a different representation.

Our brain interprets symbols by processing them instantly with all the information connected to them, along with other information and their context. As we have studied at GRI, the data conveyed by the profiles rapidly becomes extensive. With the profiles, once learned, users can enhance the quality of their judgment whenever necessary, which, with people, can be constant, especially in management. Once learned, the visual condensed representation is the most powerful aspect of the measure.

Using Reports and Charts

When used by end users who do not understand the adaptive profiles, a report helps convey their meaning. The narrative is built by analyzing the factors, their interactions, and the three graphs, as certified users can do. However, reports can't adapt their narrative to a context they don't know yet; a context that is nuanced and constantly changing. A report cannot replace feedback sessions, which allow for analysing the context, adapting the narrative, empathizing, asking and answering questions in real time.

Reports cannot provide the conciseness that adaptive profiles do. Personality assessment narratives are typically repetitive, using the same information to analyze various traits and types (Leadership style? Decision making style? ... ). Important nuances cannot be memorized and used along with other information. Reports don’t allow easy comparisons; adaptive profiles do.

Measures of traits presented with scatter charts or pies distort the result within their continuum, which usually starts from 0 and goes up to a higher value, such as 10. The distortion is even worse for typologies, with no intensity at all being measured, which doesn't reflect common observations. Measures of factors in the adaptive profiles display along a continuum, with a standard deviation scale, and don't have the above-mentioned issues. Measures on the extremes to the left and to the right, at four standard deviations from the mean, are so rare (around 0.006%) that capping them doesn't affect their meaning and use.

The Same Happened with Other Measures

What happens with the measures of the adaptive profiles is no different from other measures of, let’s say, time, temperature, distance, and weight. Once available with an instrument that’s practical enough and whose results can be useful and trusted over time, the measure becomes available to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of some kinds. It can then be shared and used to participate in a collective experience that was not possible before.

In the case of the adaptive profiles, rather than coming from someone’s subjective assessment—something we refer to at GRI as private techniques—the concepts being measured come from the survey technique. The GRI’s instrument brings objectivity and accuracy to the concepts being measured.

Of critical importance, as for any other measure, is its quality, utility, and practicality. The aspect of practicality with the profile is briefly discussed above. Other aspects of quality and utility have been extensively studied at GRI. They were the starting point of our research: What are we talking about? What for and for whom? Those points are discussed in other articles.

Relearning individual and group Performance

Like with any other measure and instrument, trusting their utility for the first time requires understanding the limitations of what they are replacing and envisioning the benefits of the new measure. Being interested in a more objective, refined understanding of how people function and adapt only happens after experiencing the limitations of one's own private techniques and eventually of other techniques being used.

Learning the adaptive profiles takes little time, typically around 15 hours. Both their learning and use happen with an interest and curiosity in how people and organizations can better perform. The adaptive profile will then be useful for that end, not just by looking at individuals but also at what their organization needs to perform, and for which the profiles will provide new perspectives.