Large Exploration Field

Introduction

An important aspect of developing the GRI’s framework is identifying the “Uses of assessment techniques." The object of the investigation, the use process, determines how it will be examined. This article outlines the large exploration field and how the observations were conducted.

Generalities

The study addresses the questions of the "how" and the "what" of a set of current events; since the use process has not been analyzed yet, case studies based on stories of past and current phenomena from multiple sources of evidence are the logical way to explore.

A case study allows for analysis of the process variable "Use of the assessment technique" within its evolving context, involving different users, organizations, and contact with various techniques. The significance of identifying new data and cross-site forms has been highlighted by Eisenhardt[1]. Therefore, all potential users of assessment techniques were considered: CEOs, executives, board directors, presidents, vice presidents, operational and functional managers, human resources managers, employees, consultants, facilitators, coaches, psychologists, and psychiatrists, etc.

The organizations came from various industrial sectors, sizes, and countries. In the first phase of the study, the focus was on personality assessment, which enabled comparisons and analyses with all types of other techniques. The new general framework includes all kinds of assessment techniques, notably the parallel techniques and the assessment developed at GRI as a result of the initial phase. The latter served as a benchmark for evaluating other techniques and for representing individual and group performance.

Direct observational data, systematic interviews, and public and private records were included in the exploration. All facts about the flow of events of the observed phenomenon are potential data. A field exploration with many varied and contrasting cases is useful to allow concepts and connections to emerge naturally, which are generalizable, reproducible, and cumulative. From there, a theoretical model linking concepts or variables can be built to explain the phenomenon studied, as broadly as possible.

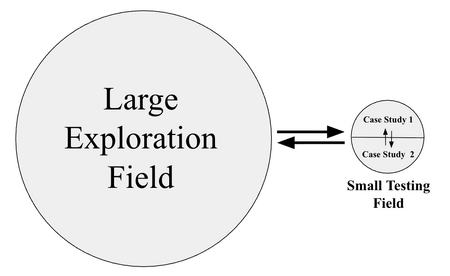

It is important to differentiate this field, or “large exploration field,” from the one formed by the case studies on which the framework being developed, or “small testing field,” was thoroughly tested during phase 1. The interaction between the large exploration field and the small testing field occurred after the model was built; a complete separation between the two would have been artificial. The analyses on the small testing field enabled the generation of new observations on the large exploration field, and vice versa, by oscillating between the two, but only during the testing phase. The interactions between the two fields can be represented as follows. The arrows illustrate the exchanges between the fields and between the cases themselves.

Three Phases

During the first phase of the study, from January 1, 1997, to June 30, 2004, the large observation field included people and companies with whom I was in contact. Each contact recorded had either a partial or full transcription, referred to below as a "transcription unit." In a partial transcription, only the following details were noted: the person's name, their title, organization, date, time, and meeting location. In a full transcription, descriptive and explanatory notes were also added. That’s during this first phase that the original framework was developed.

From July 1, 2004, to June 30, 2011, I continued taking notes intermittently. The large field shifted to the San Francisco Bay Area. In June 2006, at the end of phase 1, the observations reached saturation, although the new field began to yield fresh insights. It was during this period that GRI emerged, partly as a result of phase 1.

From July 1, 2011, through 2025, note-taking persisted, supported by new data from GRI, discussions with new prospects, clients, and consultants worldwide, as well as during gatherings at Stanford University, meetings, and events predominantly in Silicon Valley. The current general framework was devised during this third phase.

The Large Exploration Field

The observation sources forming the larger exploration field of this study are both primary: the field on which the observations were conducted, and secondary: testimonials from consultants and documents. It is from these two sources that it was possible to analyze the use of assessment techniques. The two sources of observation are detailed below.

Secondary sources

Secondary sources include the following:

- Documents on various assessment techniques, such as information available online, technical documentation, commercial brochures from publishers, and user newsletters. I collected information on about 150 assessment techniques.

- Cases, uses, and observations reported by users and consultants of assessment techniques were recorded in my field notes.

Whenever I researched on the Internet or read books, papers, and articles in any area relevant to the study, I noted down the most interesting websites and readings. I also took notes to comment on the works, theories, or authors I was studying.

Taking Notes

During the first phase, in August 2003, I fully transcribed my diary onto a laptop and added (retrospectively) my observations from the first meetings since January 1, 1997. Between September 1, 2003, and June 30, 2004, I kept systematic notes to closely match my observations. For instance, I took notes during or after phone calls or lunch, and at worst, I summarized the observations at the end of each day. This methodical work took about one to two hours daily, six to seven days a week, for ten months. Field notes were stored in MS Word files, with each transcription unit organized in tables. The total work comprises 1,504 transcription units across 478 pages (180,00 words).

Besides taking notes on my laptop, I used a composition notebook when the laptop wasn't available to quickly sketch diagrams and jot down ideas in real-time. This process helped generate some concepts. For instance, waiting times at airports provided opportunities to gather information in this way. The notes are mainly descriptive. They are completed by tests of conjectures, which help clarify observations through triangulation whenever possible. I did my best to follow this order during transcriptions and analysis: description first, then analysis and conjecture second. Sometimes, the two are mixed, especially when the situations and thoughts were intense and productive; I wrote as it came.

Notes were taken in various settings: after business breakfasts, lunches, dinners, dinner debates, and discussions, in company corridors or waiting rooms, during car rides or train trips, following group presentations, participation in public conferences, academic talks, symposiums, and more. It’s worth noting that the most inspiring insights often emerged during informal moments. When the transcriptions were systematized, they helped crystallize observations and enabled logical progress Notes on group trainings I led were mostly taken during breaks. Participants’ reactions to their learning and use — including questions, doubts, convictions, emotions, and more — were documented in context. The most interesting ideas usually emerged at the end of group trainings, when participants felt more confident and relaxed with the discussions. Lunch breaks allowed interaction with participants, helping me better understand each person’s motivation, expectations, and needs. Over seven and a half years, I conducted seventy-seven group training sessions for 500 people, with an average of six to seven participants per session, roughly half managers and half human resources professionals.

During the second phase from 2006 to 2011, the notes were less systematic, though they focused on new uses and contexts that I hadn’t yet experienced in the medical field, working with pharmaceutical companies, startups, large Silicon Valley technology firms, PE and VC investment firms, banks, law firms, assessment publishers, and non-profits. Most observations were made in the USA, with fewer in Europe, Asia, and West Africa. These notes also included new assessment techniques, concepts, and methods. During this period, the Internet revolutionized access to data and its use. Fewer notes were recorded in the composition notebook.

Since 2012, during the third phase, observations increased significantly thanks to GRI’s platform and training availability. Consultants, prospects, and clients broadened the exploration field and created new opportunities for observations and testing new ideas. New regions included South America, Spanish-speaking countries (Mexico, Chile, Spain), Brazil, and Australia. The GRI enabled comparisons of assessments on real cases involving people and companies from all these regions. During this time, the list of assessments more than doubled. It became increasingly easier to collect information, analyze statistics, and publish results.

Feedback Sessions

The feedback sessions were meaningful times spent connecting with individuals and gathering new information. These sessions, which lasted an average of twenty minutes to an hour—though I sometimes conducted sessions that lasted three hours—enabled the development of productive discussions. I conducted around 650 feedback sessions and analyzed about 2,000 profiles during the first phase. In the second and third phases, I estimate I conducted approximately 1,200 feedback sessions and analyzed over 7,000 profiles. To this last figure, we must add more than 10,000 profiles used to assist clients in recruitment, team building, company reviews, and reorganizations—all without personally conducting the feedback sessions. These estimates are based on the profiles and other data collected by the platform.

Monitoring companies over periods of up to fourteen years allowed me to observe how assessment techniques are used over time. In some companies, I have seen several Managing Directors or Human Resources Directors succeed one another. During this period, some companies were absorbed, merged, sold, or ceased operations. Those recording minimal activity are exceptions; most experience significant change. This has helped me appreciate how shifts in people and organizations influence the use of assessment techniques. By tracking individuals through organizational transitions, I could observe how their use of assessment methods evolved in different contexts.

Individuals’ Characteristics

Of the 1,116 people I met over 7.5 years during the first phase, and for whom I systematically kept notes, I initially identified 80 groups based on their function. These groups were later narrowed down to six. The details for each group are as follows:

| Titles | Nbr. People Distribution | Details |

|---|---|---|

| CEO | 214 – 20% | 80 General Managers, 100 Chief Executive Officers. The other persons are the Chairman (without General Management), retired Founders, Partners of consulting companies, and other persons in General Management positions of international groups. |

| Directors | 317 – 29% | 19 Sales Managers, 28 Store Managers, 9 Marketing Managers, 26 Regional Sales Managers, 9 Hotel Managers, 8 Operational Managers. The other people are procurement managers, division managers, plant managers, client service managers, sorting center managers, logistics managers, IT managers, financial managers, administrative managers, creative managers, etc. |

| HRD | 123 – 11% | 95 HRDs, 28 HRDs from divisions or senior HR managers close to the Group HRD. |

| HR | 210 – 19% | Human resources advisers, recruitment managers, site HR managers, project managers, mobility managers, training managers, and executive development managers all included. |

| Consultants | 167 – 15% | 74 consultants, coaches, advisers of all kinds, 16 journalists, 4 magazine editors, 22 university or business school professors, 4 social science researchers, 5 lawyers, 4 business angels, 2 doctors, 2 priests , 1 photographer, 1 physiotherapist, 1 morphopsychologist. |

| Employees | 71 – 6% | Administrative employees, assistants, and secretaries. |

It did not seem that the age, diploma, or gender criteria had any interest with respect to the specific question. The people I met were of all ages, from 20 years old for the youngest finishing their studies, up to about 80 years old for retired managers. Women are particularly present in human resources, while I more often met men in operations. A wide range of diplomas is represented in the sample at all levels.

Organizations’ Characteristics

The number of companies on which I took notes in the first phase of building the framework is 501. Over seven and a half years, this averages about six new companies per month. These companies were prospective clients or existing clients, along with other organizations I stayed in close contact with after retreats, events, and group presentations. Most notes from this phase focused on headquarters and subsidiaries of global companies. Out of the 501 companies, 147 were clients across various industries. Additionally, 127 organizations were international groups. The distribution of these companies by industry is as follows:

| Industries | Distribution |

|---|---|

| Heavy industries, pharmaceutical industries, transport, the army, and design offices for industry. | 37% |

| Business services, telecommunications companies, theme parks, hotels, and restaurants. | 19% |

| Consulting, recruitment, IT management, and interim. | 13% |

| Distribution and trade. | 9% |

| Banking, insurance, finance, audit, and law firms. | 7% |

| Press, television, and communication agency. | 7% |

| University, trade, and business schools. | 4% |

| Nonprofits and charities. | 4% |

The breakdown of companies by headcount is as follows:

| Effective | Distribution |

|---|---|

| 1 to 10 people | 20% |

| 11 to 50 people | 10% |

| 51 to 300 people | 25% |

| 301 to 2000 people | 23% |

| 2000 to 10,000 people | 12% |

| More than 10,000 people | 10% |

Notes

- ↑ Eisenhardt K. M. (1989). Building Theories from Case Study Research, Academy of Management Review, vol. 14, n° 4, p 541.