Large Exploration Field

Introduction

A fundamental aspect of developing the GRI’s framework is identifying the “Uses of assessment techniques." The object of the investigation, which is the "use" process, determines how it is examined. This article outlines the large exploration field and how the observations were conducted by taking notes on people, including during feedback and learning sessions, the organizations where they work, the assessment techniques being used, and the concepts being measured.

Generalities

The building of the framework addresses the questions of the "how" and the "what" of a set of current events relating to the "use of assessment techniques"; since the use process has not been analyzed to the fullest extent of users we are considering, case studies based on stories of current and past phenomena from multiple sources of evidence are the logical way to explore. Case studies allow for analyzing the process variable "Use of assessment techniques" within their evolving context, involving different users, organizations, publishers, and contacts with various concepts, methods, and techniques. The significance of identifying new data and cross-site forms has been emphasized by Eisenhardt[1].

Users: During phase 1 of the research (see below), the following potential users of assessment techniques were considered: CEOs, executives, board directors, presidents, vice presidents, operational and functional managers, human resources managers, employees, consultants, and facilitators. During phases 2 and 3, new techniques and users emerged and were included, such as coaches, medical doctors, marketers, economists, psychologists, and psychiatrists.

Organizations: The organizations analyzed came from various industrial sectors, sizes, and countries. In the first phase of the study, the focus was on personality assessment, which enabled comparisons and analyses with all types of other techniques. The general framework elaborated during phases 2 and 3 included all kinds of assessment techniques, notably the parallel techniques. It also included the assessment technique developed at GRI following the research conducted in phase 1 and additional evidence gathered in phase 2. Its use helped make new observations and serve as a benchmark for evaluating other uses, concepts, and techniques. Importantly, the GRI technique also served to measure and represent organizational performance, which is the dependent variable of the framework.

Contrasting cases: Direct observational data, systematic interviews, and public and private records were included in the exploration. All facts about the flow of events of the observed phenomenon of the “Use of assessment techniques” were potential data. A field exploration with many varied and contrasting cases is useful to allow concepts and connections to emerge naturally, which can be generalizable, reproducible, and cumulative. From there, a theoretical model connecting concepts and variables was built to explain the phenomenon studied as broadly as possible.

The Three Phases

- Phase 1. During the first phase of the study, from January 1, 1997, to December 31, 2006, the large observation field included people and companies with whom I was in contact. Each contact recorded had either a partial or full transcription, referred to below as a "transcription unit." In a partial transcription, only the following details were noted: the person's name, their title, organization, date, time, and meeting location. In a full transcription, descriptive and explanatory notes were also added. That’s during this first phase that the original framework was developed.

- Phase 2. From January 1, 2007, to December 31, 2011, I continued taking notes on a large field that had shifted to the San Francisco Bay Area and other countries than predominantly France and the USA. Although the new field began to yield fresh insights, the observations that led to the original framework were saturated. It was during this second phase that the specific question was enlarged to include other assessment techniques, rather than only personality assessments. It's also at that time that the GRI survey and the adaptive profiles emerged, in large part as a result of phase 1 and the new observations from the larger field.

- Phase 3. From January 1, 2012, through 2025, note-taking persisted, supported by new data from GRI, discussions with new prospects, clients, and consultants worldwide, and gatherings at Stanford University[2], meetings, and other events predominantly in Silicon Valley. The current general framework was devised during this third phase.

The Large Exploration Field

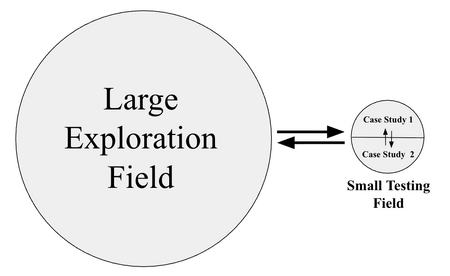

It is important to differentiate the large exploration field from the one formed by the case studies or “small testing field, on which the framework being developed was thoroughly tested during phase 1. The interaction between the large exploration field and the small testing field occurred after the model was built; a complete separation between the two would have been artificial.

The analyses on the small testing field of phase 1 enabled the creation of new observations on the large exploration field, and vice versa, by going back and forth between the two, but only during the testing phase. The two fields are represented as follows, with the arrows illustrating the exchanges between the fields and between the two cases of the small testing field itself.

The observation sources forming the larger exploration field of this study are both primary: the field on which the observations were conducted, and secondary: testimonials from consultants, and documents. It is from these two sources that it was possible to analyze the use of assessment techniques. The two sources of observation and how the observations were conducted are detailed below.

Primary Sources–Taking Notes Phase 1

During the first phase, in August 2003, I fully transcribed my diary onto a laptop and added (retrospectively) my observations from the first meetings since January 1, 1997. Between September 1, 2003, and June 30, 2004, I kept systematic notes to closely match my observations. For instance, I took notes during or after phone calls or lunch, and at worst, I summarized the observations at the end of each day. This methodical work took about one to two hours daily, six to seven days a week, for ten months. Field notes were stored in MS Word files, with each transcription unit organized in tables. The total work comprises 1,504 transcription units across 478 pages (180,00 words).

Besides taking notes on my laptop, I used a composition notebook when the laptop wasn't available to quickly sketch diagrams and jot down ideas in real-time. This process helped generate some concepts. For instance, waiting times at airports provided opportunities to gather information in this way. The notes are mainly descriptive. They are completed by tests of conjectures, which help clarify observations through triangulation whenever possible. I did my best to follow this order during transcriptions and analysis: description first, then analysis and conjecture second. Sometimes, the two are mixed, especially when the situations and thoughts were intense and productive; I wrote as it came.

Notes were taken in various settings: after business breakfasts, lunches, dinners, dinner debates, and discussions, in company corridors or waiting rooms, during car rides or train trips, following group presentations, participation in public conferences, academic talks, symposiums, and more. It’s worth noting that the most inspiring insights often emerged during informal moments. When the transcriptions were systematized, they helped crystallize observations and enabled logical progress.

Notes on group trainings I led were mostly taken during breaks. Participants’ reactions to their learning and use — including questions, doubts, convictions, emotions, and more — were documented in context. The most interesting ideas usually emerged at the end of group training, when participants felt more confident and relaxed with the discussions. Lunch breaks allowed interaction with participants, helping me better understand each person’s motivation, expectations, and needs. Over seven and a half years, I conducted seventy-seven group training sessions for 500 people, with an average of six to seven participants per session, roughly half managers and half human resources professionals.

Primary Sources–Taking Notes Phase 2

During the second phase from 2006 to 2011, the notes were less systematic, though they focused on new uses and contexts that I hadn’t yet experienced in the medical field, working with pharmaceutical companies, startups, large Silicon Valley technology firms, PE and VC investment firms, banks, law firms, assessment techniques publishers, and non-profits. Most observations were made in the USA, with fewer in Europe, Asia, and Africa. These notes also included new assessment techniques, concepts, and methods. During this period, the Internet revolutionized access to data and its use. Fewer notes were recorded in the composition notebook.

Primary Sources–Taking Notes Phase 3

Since 2012, during the third phase, observations increased significantly thanks to GRI’s platform and training availability. Consultants, prospects, and clients broadened the exploration field and created new opportunities for observations and testing new ideas. New regions included South America, Spanish-speaking countries (Mexico, Chile, Spain), Brazil, and Australia. The GRI enabled comparisons of assessments on real cases involving people and companies from all these regions. During this time, the list of assessments more than doubled. It became increasingly easier to collect information, analyze statistics, and publish results.

Primary Sources–Feedback Sessions

The feedback sessions were meaningful times spent connecting with individuals and gathering new information. These sessions, which lasted an average of thirty minutes to an hour—though I sometimes conducted sessions that lasted three hours—enabled the development of productive discussions. I conducted around 650 feedback sessions and analyzed about 2,000 profiles during the first phase. In the second and third phases, I estimate approximately 1,200 feedback sessions and over 7,000 profile analyses. To this last figure, more than 10,000 profiles need to be added, for assisting clients in recruitment, team building, company reviews, and reorganizations, without conducting the feedback sessions myself. These estimates are based on the profiles and other data from the platform.

Observing companies, sometimes over periods of up to fourteen years, allowed me to analyze how assessment techniques are used over time. In some companies, I have seen several Managing Directors or Human Resources Directors succeed one another. During this period, some companies were absorbed, merged, sold, or ceased operations. Those with minimal activity are exceptions; most experience significant change. This has helped me appreciate how shifts in people and organizations influence the use of assessment techniques. By tracking individuals through organizational transitions, I could observe how their use of assessment techniques evolved in different contexts.

Secondary Sources

Secondary sources include the following:

- Documents on various assessment techniques, such as information available online, technical documentation, commercial brochures from publishers, and user newsletters. I collected information on about 150 assessment techniques.

- Cases, uses, and observations reported by users and consultants of assessment techniques were recorded in my field notes.

Whenever I researched on the Internet or read articles, books, and papers in areas relevant to the study, I took notes and kept track of the sources, such as websites. I also took notes to comment on the works, theories, or authors I was studying. AI, having recently gained new abilities to reach out, analyze, and synthesize information, made it urgent for us to use a wiki to gather and publish information on our own.

Individuals’ Characteristics

Of the 1,116 people I met over 7.5 years during the first phase, and for whom I systematically kept notes, I initially identified 80 groups based on their function. These groups were later narrowed down to six. The details for each group are as follows:

| Titles | Nbr. People Distribution | Details |

|---|---|---|

| CEO | 214 – 20% | 80 General Managers, 100 Chief Executive Officers. The other persons are the Chairman (without General Management), retired Founders, Partners of consulting companies, and other persons in General Management positions of international groups. |

| Directors | 317 – 29% | 19 Sales Managers, 28 Store Managers, 9 Marketing Managers, 26 Regional Sales Managers, 9 Hotel Managers, 8 Operational Managers. The other people are procurement managers, division managers, plant managers, client service managers, sorting center managers, logistics managers, IT managers, financial managers, administrative managers, creative managers, etc. |

| HRD | 123 – 11% | 95 HRDs, 28 HRDs from divisions or senior HR managers close to the Group HRD. |

| HR | 210 – 19% | Human resources advisers, recruitment managers, site HR managers, project managers, mobility managers, training managers, and executive development managers all included. |

| Consultants | 167 – 15% | 74 consultants, coaches, advisers of all kinds, 16 journalists, 4 magazine editors, 22 university or business school professors, 4 social science researchers, 5 lawyers, 4 business angels, 2 doctors, 2 priests , 1 photographer, 1 physiotherapist, 1 morphopsychologist. |

| Employees | 71 – 6% | Administrative employees, assistants, and secretaries. |

It did not seem that the age, diploma, or gender criteria had any interest with respect to the specific question. The people I met were of all ages, from 20 years old for the youngest finishing their studies, up to about 80 years old for retired managers. Women are particularly present in human resources, while I more often met men in operations. A wide range of diplomas is represented in the sample at all levels.

Organizations’ Characteristics

The number of companies on which I took notes in the first phase of building the framework is 501. Over seven and a half years, this averages about six new companies per month. These companies were prospective clients or existing clients, along with other organizations I stayed in close contact with after retreats, events, and group presentations. Most notes from this phase focused on headquarters and subsidiaries of global companies. Out of the 501 companies, 147 were clients across various industries. Additionally, 127 organizations were international groups. The distribution of these companies by industry is as follows:

| Industries | Distribution |

|---|---|

| Heavy industries, pharmaceutical industries, transport, the army, and design offices for industry. | 37% |

| Business services, telecommunications companies, theme parks, hotels, and restaurants. | 19% |

| Consulting, recruitment, IT management, and interim. | 13% |

| Distribution and trade. | 9% |

| Banking, insurance, finance, audit, and law firms. | 7% |

| Press, television, and communication agency. | 7% |

| University, trade, and business schools. | 4% |

| Nonprofits and charities. | 4% |

The breakdown of companies by headcount is as follows:

| Effective | Distribution |

|---|---|

| 1 to 10 people | 20% |

| 11 to 50 people | 10% |

| 51 to 300 people | 25% |

| 301 to 2000 people | 23% |

| 2000 to 10,000 people | 12% |

| More than 10,000 people | 10% |