Hypotheses Formulation: Difference between revisions

| (31 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[File:GRI | [[File:GRI TPU.png|right|250px]] | ||

The hypotheses of the general framework | =Introduction= | ||

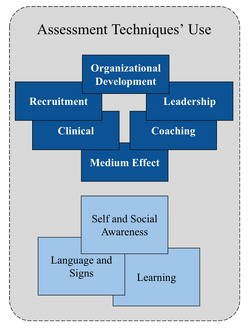

The hypotheses of the general framework have been formulated to answer the specific question on the relationship between the “Use of assessment techniques” and “Performance”. The operational content of the theoretical concepts "Use of assessment technique" was clarified during the analysis of the uses, which led to the consideration of nine categories. In this article, the hypothesis and how they were formulated are presented. | |||

=Formulation Criteria= | |||

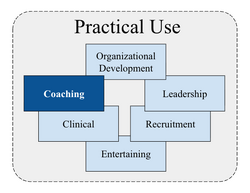

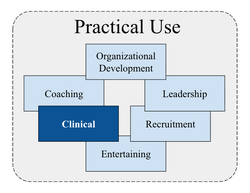

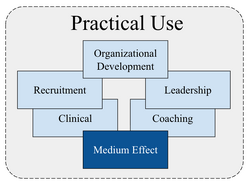

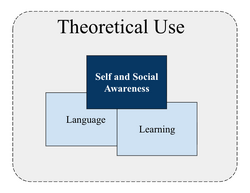

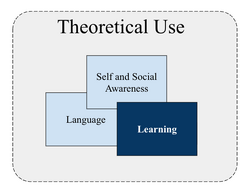

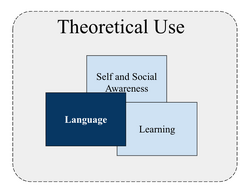

Six primary uses of a practical nature have been identified in “Organizational Development”, “Leadership,” “Coaching,” “Recruitment,” “Clinical,” and as a “Medium.” Three uses of a theoretical nature have been identified: “Self and Social Awareness,” “Learning,” and “Language.” Of a more abstract nature, these three theoretical uses are present transversally in the six practical ones. | |||

To operationally define the relationship between the “Use of assessment techniques” and “Performance,” we say that there is agreement when, over time, performance increases, while the “Use of assessment techniques” increases too. Conversely, there is disagreement when the performance decreases or does not change, while the “Use of the assessment technique” increases. | To operationally define the relationship between the “Use of assessment techniques” and “Performance,” we say that there is agreement when, over time, performance increases, while the “Use of assessment techniques” increases too. Conversely, there is disagreement when the performance decreases or does not change, while the “Use of the assessment technique” increases. | ||

The confrontation between the concepts of “Use of assessment technique” constructed inductively and the literature (obtained deductively) forms provisional refutable and confirmable hypotheses to be tested<ref>Zaltman, G, Pinson, C., Angelmar, R. (1973). Metatheory and Consumer Research, New York, Holt, Rinehart and Wintson.</ref>. The hypotheses are formulated in such a way that they make it possible to account validly for the relationship between the “Use of assessment technique” and “Performance”. The formulation of hypotheses was made to satisfy the criteria of plausibility, verifiability, precision, generalization, and communicability<ref>Mace G, Pétry F. (2000). Guide d’élaboration d’un projet de recherche en science sociales. DeBoeck Université.<br/>The criteria of plausibility, verifiability, precision, generalization, and communicability [[Hypotheses_Criteria|are discussed in a separate note here.]]</ref>. | The confrontation between the concepts of “Use of assessment technique” constructed inductively and the literature (obtained deductively) forms provisional refutable and confirmable hypotheses to be tested<ref>Zaltman, G, Pinson, C., Angelmar, R. (1973). Metatheory and Consumer Research, New York, Holt, Rinehart and Wintson.</ref>. The hypotheses are formulated in such a way that they make it possible to account validly for the relationship between the “Use of assessment technique” and “Performance”. The formulation of hypotheses was made to satisfy the criteria of plausibility, verifiability, precision, generalization, and communicability<ref>Mace G, Pétry F. (2000). Guide d’élaboration d’un projet de recherche en science sociales. DeBoeck Université.<br/>The criteria of plausibility, verifiability, precision, generalization, and communicability [[Hypotheses_Criteria|are discussed in a separate note here.]]</ref>. | ||

=Use in Organizational Development= | =Use in Organizational Development= | ||

[[File:PU Organization.png|right|250px]] | [[File:PU Organization.png|right|250px]] | ||

Among the various uses of assessment techniques, those at an organizational level | Among the various uses of assessment techniques, those at an organizational level are highly significant, providing accurate information for analyzing teams, departments, and management during major changes like mergers or reorganizations. This information is crucial for making fast, important decisions on people, impacting their future development, engagement, and performance. Accurate job envisioning at all company levels is strategic, and the characteristics of recruits and managers must align with the vision. GRI uses Position Behavior Indicators (PBI) and Team Behavior Indicators (TBI) to guide recruitment and organizational development. Research suggests a better understanding of individual variables is necessary for group analysis<ref>Macy M. W., Willer R. (2002). From Factors to Actors: Computational Sociology and Agent-Based Modeling. Annual Review of Sociology, 28, 143-166.<br/>Axtell, Robert L., and J. Doyne Farmer. 2025. "Agent-Based Modeling in Economics and Finance: Past, Present, and Future." Journal of Economic Literature 63 (1): 197–287. DOI: 10.1257/jel.20221319</ref>. Given the capacity of assessment techniques to bring objective information at both macro and micro levels, their use in organizational development is expected to have a strong and positive impact on performance<ref>Alexander J. C., Giesen B., Münch R., Smelser N. (1987). The Micro-macro link. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.</ref>. These observations make it possible to construct the following Hypothesis 1: | ||

'''Hypothesis 1''': The agreement between the use of the assessment technique and performance is more likely if the technique is used in organizational development. | '''Hypothesis 1''': The agreement between the use of the assessment technique and performance is more likely if the technique is used in organizational development. | ||

| Line 25: | Line 18: | ||

=Use in Leadership= | =Use in Leadership= | ||

[[File:PU Leadership.png|right|250px]] | [[File:PU Leadership.png|right|250px]] | ||

Use in Leadership covers employee motivation, engagement, shared vision, communication, people management, goal setting, feedback, periodic review, and team development, all under the leader's responsibility<ref>The items mentioned are only examples; the list continues. As mentioned, it was inspired both deductively, by literature in leadership, and inductively, by observation from the exploration field.</ref>. This use is distinct from HR or coaching, particularly in its effects when leaders use assessment information directly. Leadership research, such as by Kouzes and Posner, highlights the essential need for people and social skills<ref>Kouzes, J. M., & Posner, B. Z. (2023). The leadership challenge: How to make extraordinary things happen in organizations (7th ed.). John Wiley & Sons.</ref>. Assessment techniques aid in these skills, including inspiring a shared vision and enabling others to act. The relevance of a leader's style (democratic, autocratic, etc.) depends on the situation<ref>Hersey, P., Blanchard, K. H., Jhonson, D. E. (1996). Management of organizational behavior. Utilizing human resources. Prentice Hall. 6th Edition. First published in 1969.</ref>, requiring adaptive capacity<ref>Vroom, V. H., Jago A. G. (2007). The Role of the Situation in Leadership. American Psychologist. Vol. 62, No. 1, p. 17-24.</ref>. Assessment information provides new insights, enhancing a leader's ability to build team members' leadership<ref>Bass B. M. (1990). Bass and Stogdill’s Handbook of Leadership: theory, research, and managerial application. New York: Free Press.</ref>. Furthermore, a leader’s most complex challenges are adaptive, benefiting from the objective data provided by assessment techniques. This fundamental link suggests a positive effect on performance. These observations make it possible to construct the following Hypothesis 2. | |||

The | |||

'''Hypothesis 2''': The agreement between the use of the assessment technique and the performance is more likely if the technique is used in leadership. | '''Hypothesis 2''': The agreement between the use of the assessment technique and the performance is more likely if the technique is used in leadership. | ||

| Line 40: | Line 24: | ||

=Use in Recruitment= | =Use in Recruitment= | ||

[[File:PU Recruitment.png|right|250px]] | [[File:PU Recruitment.png|right|250px]] | ||

The scope of Recruitment includes selection, sourcing, interviewing, skills assessment, succession planning, and promotion, managed by HR or, in smaller firms, by management<ref>As for leadership, the list for recruitment is not limited to those items. These are just examples. The list continues.</ref>. These functions are often outsourced and increasingly supported by AI. Assessment techniques have a long history in mass recruitment, executive search, and promotions. Research has heavily focused on mass recruitment, ensuring compliance with regulations like EEOC and ADA, work-relatedness, reliability, and validity. When these criteria are met, the techniques add incremental value to improving performance. Interviewers can combine objective assessment data with immediate subjective insights. GRI observes that assessment results are used to quickly tailor the job to the candidate or vice-versa, with the quality of information, job relevance, and the candidate's behavioral adaptability being crucial decision elements. These observations lead to the formulation of the following Hypothesis 3. | |||

Assessment techniques have | |||

'''Hypothesis 3''': The agreement between the use of the assessment technique and the performance is more likely if the assessment technique is used in recruitment. | '''Hypothesis 3''': The agreement between the use of the assessment technique and the performance is more likely if the assessment technique is used in recruitment. | ||

| Line 50: | Line 30: | ||

=Use in Coaching= | =Use in Coaching= | ||

[[File:PU Coaching.png|right|250px]] | [[File:PU Coaching.png|right|250px]] | ||

Coaching has | Coaching, which has grown since the late 1990s, readily uses assessment techniques like the MBTI<ref>Möeller, H., and Kotte, S. (2022). “Assessment in coaching” in International handbook of evidence-based coaching: theory, research and practice. eds. S. Greif, H. Möller, W. Scholl, J. Passmore, and F. Müller (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 55–64.<br/>Passmore, J. (Ed.). (2012). Psychometrics in coaching: Using psychological and psychometric tools for development (2nd ed.). Kogan Page.</ref>. This use was incorporated into the revised framework due to its clear application in coaching and mentoring for individual development and team building. Coaches commonly use techniques like 360-degree feedback and personality typologies, which differ from the trait assessments in recruitment<ref>Sutton, J. (2020) Coaching styles explained: 4 different approaches. Psychology.com. https://positivepsychology.com/coaching-styles/</ref>. The GRI factor approach is also used successfully by coaches to develop self-efficacy. Coaching is separate from recruitment and distinct from leadership development, focusing more on personal development at work and in life<ref>Passmore, J., & Tee, D. (2021). Coaching researched: A coaching psychology reader. John Wiley & Sons.</ref>. The main impact of assessment techniques in coaching is the enhancement of self-efficacy and self/social awareness<ref>Theeboom, T., Beersma, B., and van Vianen, A. E. (2014). Does coaching work? A meta-analysis on the effects of coaching on individual level outcomes in an organizational context. J. Posit. Psychol. 9, 1–18. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2013.837499<br/>Cannon-Bowers, J. A., Bowers, C., Carlson, M., Doherty, P., Evans, S., & Hall, G. (2023). Workplace coaching: A meta-analysis and recommendations for advancing the science of coaching. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, Article 1204166. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1204166</ref>. Studies show moderate positive effects on individual outcomes and efficacy, which, while not the direct focus, may subsequently impact organizational performance. For this reason, the following Hypothesis 4 was constructed: | ||

Coaching | |||

The | |||

'''Hypothesis 4''': The agreement between the use of the assessment technique and the performance is more likely if the technique is used in coaching. | '''Hypothesis 4''': The agreement between the use of the assessment technique and the performance is more likely if the technique is used in coaching. | ||

| Line 62: | Line 36: | ||

=Use in Clinical Settings= | =Use in Clinical Settings= | ||

[[File:PU Clinical.png|right|250px]] | [[File:PU Clinical.png|right|250px]] | ||

Clinical Settings refers to health and well-being services, like Employee Assistance Programs (EAP), which are a growing corporate standard. Assessment techniques originated in clinical practice in the late 1890s and are still used by clinicians for diagnosis, therapy, and counseling. The use of these health services, often aided by new digital tools and AI, has increased since the pandemic. These clinical services are distinct from coaching, focusing on therapy, and have proven effective in treating mental health issues<ref>Lyra (2025). State of Workforce Mental Health Report. A report from Mental Health Innovation Summit 2025. https://www.lyrahealth.com/resources/report/2025-state-of-workforce-mental-health-report/<br/>Kuang, T., Guo, C., Ren, M., Fu, L., Li, C., Ma, S., & Li, R. (2025). The effectiveness of e-mental health interventions on stress, anxiety, and depression symptoms in healthcare professionals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health, 25(1), 1083. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-024-02565-6</ref>, thereby improving work productivity and reducing costs<ref>World Health Organization. (2024, September 2). Mental health at work. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-at-work</ref>. GRI has observed clinicians using non-traditional assessments, such as MBTI or the Enneagram, to gain unique insights for diagnosing individual challenges and counseling work-related issues. The more nuanced information from assessment techniques is expected to help improve mental health, remove systemic workplace factors, enhance self-awareness, and consequently improve organizational performance. These observations make it possible to construct the following Hypothesis 5: | |||

</ref>, and | |||

'''Hypothesis 5''': The agreement between the use of the assessment technique and the performance is more likely if the technique is used in clinical settings. | '''Hypothesis 5''': The agreement between the use of the assessment technique and the performance is more likely if the technique is used in clinical settings. | ||

=Use | =Use for Medium Effect= | ||

[[File:PU | [[File:PU Medium.png|right|250px]] | ||

Assessment techniques | Assessment techniques, by providing results, can be impressive, often giving an impression of truth through numbers, regardless of the actual quality. The rapid development of new techniques is now facilitated by AI. The revised framework includes three parallel types of assessment techniques: subjective Personal techniques, Common techniques for culture fit, and Esoteric techniques, all competing within organizations. Assessment techniques are curious and popular, often appearing in magazines and online formats for interactivity. They serve as a medium to entertain and initiate discussions, regardless of their validity or seriousness. This 'medium effect' is distinct and can be observed, but its connection to performance is considered indirect, often occurring in conjunction with other uses. These observations allow us to formulate the following Hypothesis 6: | ||

The | |||

Assessment techniques | |||

'''Hypothesis 6''': The agreement between the use of the assessment technique and the performance is more likely if the technique has an entertaining effect. | '''Hypothesis 6''': The agreement between the use of the assessment technique and the performance is more likely if the technique has an entertaining effect. | ||

| Line 86: | Line 48: | ||

=Use in Self and Social Awareness= | =Use in Self and Social Awareness= | ||

[[File:TU Awareness.png|right|250px]] | [[File:TU Awareness.png|right|250px]] | ||

Assessment techniques are used in feedback | Assessment techniques are used in feedback to foster personal growth by helping participants identify strengths, communication style, and decision-making patterns. Regardless of the varying quality and presentation of techniques, they function as indicators of self-awareness. Sharing this information also enhances social awareness, helping individuals understand others more objectively and linking personal insights to team and company roles. Discussions on self and social awareness are central to social sciences, and this domain is a major part of the growing personal development market. Information from assessments can guide future growth, identify adaptive challenges, improve engagement, and facilitate continuous improvement. This broad application at individual and group levels suggests that using assessment techniques for self and social awareness increases their overall impact on performance. These insights lead to the formulation of the following Hypothesis 7: | ||

Discussions | |||

Information from | |||

'''Hypothesis 7''': The agreement between the use of the assessment technique and the performance is more likely if the technique improves self and social awareness. | '''Hypothesis 7''': The agreement between the use of the assessment technique and the performance is more likely if the technique improves self and social awareness. | ||

| Line 97: | Line 54: | ||

=Use in Learning= | =Use in Learning= | ||

[[File:PU Learning.png|right|250px]] | [[File:PU Learning.png|right|250px]] | ||

Learning associated with assessment techniques varies greatly: some publishers require no certification, while others (like those for coaching or clinical use) require certification. Learning private and common techniques is often effortless, but for all techniques, the learning serves as the foundation for their effective use. At GRI, training is considered crucial for effectively using adaptive profiles in applications like leadership. To be effective, learning must be relevant, use real examples, and follow an impeccable process. While one-on-one coaching often replaces group training, T-group sessions have demonstrated value by using simple assessment techniques. Research on sensitivity training.<ref> Ibid, Bass B. M. (1990)</ref> supports the positive effects of leadership training courses, and a well-developed assessment technique can be a fundamental element of leadership training. Crucially, learning a new assessment technique is a non-instantaneous process that develops over time through continuous practice and application, reinforcing the skills and increasing their effectiveness and impact on performance. These points lead to the formulation of the following Hypothesis 8: | |||

At GRI, | |||

'''Hypothesis 8''': The agreement between the use of the assessment technique and the performance is more likely if its learning is nuanced and deep, rather than superficial, and continues over time. | '''Hypothesis 8''': The agreement between the use of the assessment technique and the performance is more likely if its learning is nuanced and deep, rather than superficial, and continues over time. | ||

| Line 112: | Line 60: | ||

=Use in Language= | =Use in Language= | ||

[[File:PU Language.png|right|250px]] | [[File:PU Language.png|right|250px]] | ||

A key characteristic of assessment techniques is the unique language and signs they create. Literature, including the works of Mead and Pierce<ref>Mead G. H. (1934). Mind, Self and Society from the standpoint of a behaviorist. University of Chicago Press. | |||

Peirce, C. S. (1935) Philosophical Writings of Peirce. Selection of papers between 1931 and 1935 by J. S. Buchler New York, Dover Publications.</ref>, emphasizes the importance of signs and symbols for personal connection to a system and the process of inference<ref>Carnap, R. (1988). Meaning and Necessity. A study of Semantics and Modal Logic. The University of Chicago Press. 2nd Edition. First published in 1947.<br/>Quine, W. V. (1960). Word and Object. The MIT Press.<br/>Eco, U. (1979). A theory of Semiotics. Indiana University Press. Bloomington.<br/>Eco, U. (1988). Le Signe. Histoire et analyse d'un concept. Editions Labor. Translate from: Segno, 1973.<br/>Eco, U. (1995). The Search for the Perfect Language. Blackwell Publishers.<br/>Hacking, I. (2001). Probability and Inductive Logic. Cambridge University Press.<br/>Hacking, I. (2001). Why Language Matter To Philosophy? Cambridge University Press. 13th publication. First published in 1975.<br/>Korzybski, A. (1933). Science and Sanity. Institute of General Semantics.<br/>Hayakawa, S. I. (1939). Language in thought and action. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.</ref>. The symbolic results of assessments are effective for quickly learning, recalling, and creating new inferences and skills. Assessment results come in various forms: narratives, traits with numbers, or typologies (e.g., MBTI's ESTJ or DISC's D, I, S, C). GRI's approach uses four factors to capture meaningful workplace behaviors. Once learned, this symbolic language enhances knowledge, communication, and decision-making. The conciseness, nuance, precision, memorability, and shareability of the results are critical, as they reduce ambiguity, improve decision-making, and boost the impact of other practical applications on performance. These observations allow for the formulation of the following Hypothesis 9: | |||

Once learned, | |||

'''Hypothesis 9''': The agreement between the use of the assessment technique and the performance is more likely if the results and language created facilitate their practical use. | '''Hypothesis 9''': The agreement between the use of the assessment technique and the performance is more likely if the results and language created facilitate their practical use. | ||

| Line 124: | Line 67: | ||

=Causes of Use= | =Causes of Use= | ||

[[File:Antecedents.png|right|250px]] | [[File:Antecedents.png|right|250px]] | ||

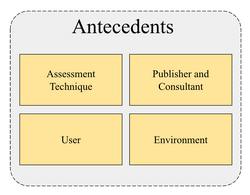

The | The use of assessment techniques is influenced by several antecedent variables: the technique's properties, the user's qualities and interests, the organization's culture and social environment, and the publisher's business model. The properties of the technique and the publisher's business model are particularly crucial, as the technique's quality enables or limits its use, and the business model impacts deployment autonomy and resources. Individual and organizational beliefs about human nature can lead to resistance towards new assessment methods. However, these beliefs can change when confronted with practical results. Adaptive profiles can predict how an assessment method will be adopted within an organization regarding process, consensus, and speed. The environment and the people evolve as the method is implemented. These observations lead to the formulation of the following Hypothesis 10. | ||

The properties of the | |||

'''Hypothesis 10''': The practical and theoretical use of the assessment technique is all the more probable if the assessment technique, publisher, environment, and individual user have appropriate characteristics. | '''Hypothesis 10''': The practical and theoretical use of the assessment technique is all the more probable if the assessment technique, publisher, environment, and individual user have appropriate characteristics. | ||

| Line 135: | Line 74: | ||

[[Category:Articles]] | [[Category:Articles]] | ||

[[Category: | [[Category:General Framework]] | ||

Latest revision as of 05:28, 27 November 2025

Introduction

The hypotheses of the general framework have been formulated to answer the specific question on the relationship between the “Use of assessment techniques” and “Performance”. The operational content of the theoretical concepts "Use of assessment technique" was clarified during the analysis of the uses, which led to the consideration of nine categories. In this article, the hypothesis and how they were formulated are presented.

Formulation Criteria

Six primary uses of a practical nature have been identified in “Organizational Development”, “Leadership,” “Coaching,” “Recruitment,” “Clinical,” and as a “Medium.” Three uses of a theoretical nature have been identified: “Self and Social Awareness,” “Learning,” and “Language.” Of a more abstract nature, these three theoretical uses are present transversally in the six practical ones.

To operationally define the relationship between the “Use of assessment techniques” and “Performance,” we say that there is agreement when, over time, performance increases, while the “Use of assessment techniques” increases too. Conversely, there is disagreement when the performance decreases or does not change, while the “Use of the assessment technique” increases.

The confrontation between the concepts of “Use of assessment technique” constructed inductively and the literature (obtained deductively) forms provisional refutable and confirmable hypotheses to be tested[1]. The hypotheses are formulated in such a way that they make it possible to account validly for the relationship between the “Use of assessment technique” and “Performance”. The formulation of hypotheses was made to satisfy the criteria of plausibility, verifiability, precision, generalization, and communicability[2].

Use in Organizational Development

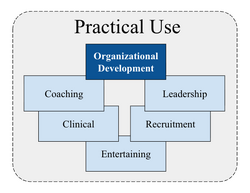

Among the various uses of assessment techniques, those at an organizational level are highly significant, providing accurate information for analyzing teams, departments, and management during major changes like mergers or reorganizations. This information is crucial for making fast, important decisions on people, impacting their future development, engagement, and performance. Accurate job envisioning at all company levels is strategic, and the characteristics of recruits and managers must align with the vision. GRI uses Position Behavior Indicators (PBI) and Team Behavior Indicators (TBI) to guide recruitment and organizational development. Research suggests a better understanding of individual variables is necessary for group analysis[3]. Given the capacity of assessment techniques to bring objective information at both macro and micro levels, their use in organizational development is expected to have a strong and positive impact on performance[4]. These observations make it possible to construct the following Hypothesis 1:

Hypothesis 1: The agreement between the use of the assessment technique and performance is more likely if the technique is used in organizational development.

Use in Leadership

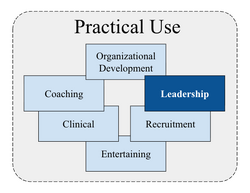

Use in Leadership covers employee motivation, engagement, shared vision, communication, people management, goal setting, feedback, periodic review, and team development, all under the leader's responsibility[5]. This use is distinct from HR or coaching, particularly in its effects when leaders use assessment information directly. Leadership research, such as by Kouzes and Posner, highlights the essential need for people and social skills[6]. Assessment techniques aid in these skills, including inspiring a shared vision and enabling others to act. The relevance of a leader's style (democratic, autocratic, etc.) depends on the situation[7], requiring adaptive capacity[8]. Assessment information provides new insights, enhancing a leader's ability to build team members' leadership[9]. Furthermore, a leader’s most complex challenges are adaptive, benefiting from the objective data provided by assessment techniques. This fundamental link suggests a positive effect on performance. These observations make it possible to construct the following Hypothesis 2.

Hypothesis 2: The agreement between the use of the assessment technique and the performance is more likely if the technique is used in leadership.

Use in Recruitment

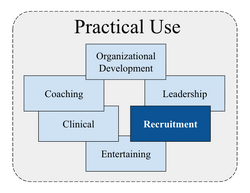

The scope of Recruitment includes selection, sourcing, interviewing, skills assessment, succession planning, and promotion, managed by HR or, in smaller firms, by management[10]. These functions are often outsourced and increasingly supported by AI. Assessment techniques have a long history in mass recruitment, executive search, and promotions. Research has heavily focused on mass recruitment, ensuring compliance with regulations like EEOC and ADA, work-relatedness, reliability, and validity. When these criteria are met, the techniques add incremental value to improving performance. Interviewers can combine objective assessment data with immediate subjective insights. GRI observes that assessment results are used to quickly tailor the job to the candidate or vice-versa, with the quality of information, job relevance, and the candidate's behavioral adaptability being crucial decision elements. These observations lead to the formulation of the following Hypothesis 3.

Hypothesis 3: The agreement between the use of the assessment technique and the performance is more likely if the assessment technique is used in recruitment.

Use in Coaching

Coaching, which has grown since the late 1990s, readily uses assessment techniques like the MBTI[11]. This use was incorporated into the revised framework due to its clear application in coaching and mentoring for individual development and team building. Coaches commonly use techniques like 360-degree feedback and personality typologies, which differ from the trait assessments in recruitment[12]. The GRI factor approach is also used successfully by coaches to develop self-efficacy. Coaching is separate from recruitment and distinct from leadership development, focusing more on personal development at work and in life[13]. The main impact of assessment techniques in coaching is the enhancement of self-efficacy and self/social awareness[14]. Studies show moderate positive effects on individual outcomes and efficacy, which, while not the direct focus, may subsequently impact organizational performance. For this reason, the following Hypothesis 4 was constructed:

Hypothesis 4: The agreement between the use of the assessment technique and the performance is more likely if the technique is used in coaching.

Use in Clinical Settings

Clinical Settings refers to health and well-being services, like Employee Assistance Programs (EAP), which are a growing corporate standard. Assessment techniques originated in clinical practice in the late 1890s and are still used by clinicians for diagnosis, therapy, and counseling. The use of these health services, often aided by new digital tools and AI, has increased since the pandemic. These clinical services are distinct from coaching, focusing on therapy, and have proven effective in treating mental health issues[15], thereby improving work productivity and reducing costs[16]. GRI has observed clinicians using non-traditional assessments, such as MBTI or the Enneagram, to gain unique insights for diagnosing individual challenges and counseling work-related issues. The more nuanced information from assessment techniques is expected to help improve mental health, remove systemic workplace factors, enhance self-awareness, and consequently improve organizational performance. These observations make it possible to construct the following Hypothesis 5:

Hypothesis 5: The agreement between the use of the assessment technique and the performance is more likely if the technique is used in clinical settings.

Use for Medium Effect

Assessment techniques, by providing results, can be impressive, often giving an impression of truth through numbers, regardless of the actual quality. The rapid development of new techniques is now facilitated by AI. The revised framework includes three parallel types of assessment techniques: subjective Personal techniques, Common techniques for culture fit, and Esoteric techniques, all competing within organizations. Assessment techniques are curious and popular, often appearing in magazines and online formats for interactivity. They serve as a medium to entertain and initiate discussions, regardless of their validity or seriousness. This 'medium effect' is distinct and can be observed, but its connection to performance is considered indirect, often occurring in conjunction with other uses. These observations allow us to formulate the following Hypothesis 6:

Hypothesis 6: The agreement between the use of the assessment technique and the performance is more likely if the technique has an entertaining effect.

Use in Self and Social Awareness

Assessment techniques are used in feedback to foster personal growth by helping participants identify strengths, communication style, and decision-making patterns. Regardless of the varying quality and presentation of techniques, they function as indicators of self-awareness. Sharing this information also enhances social awareness, helping individuals understand others more objectively and linking personal insights to team and company roles. Discussions on self and social awareness are central to social sciences, and this domain is a major part of the growing personal development market. Information from assessments can guide future growth, identify adaptive challenges, improve engagement, and facilitate continuous improvement. This broad application at individual and group levels suggests that using assessment techniques for self and social awareness increases their overall impact on performance. These insights lead to the formulation of the following Hypothesis 7:

Hypothesis 7: The agreement between the use of the assessment technique and the performance is more likely if the technique improves self and social awareness.

Use in Learning

Learning associated with assessment techniques varies greatly: some publishers require no certification, while others (like those for coaching or clinical use) require certification. Learning private and common techniques is often effortless, but for all techniques, the learning serves as the foundation for their effective use. At GRI, training is considered crucial for effectively using adaptive profiles in applications like leadership. To be effective, learning must be relevant, use real examples, and follow an impeccable process. While one-on-one coaching often replaces group training, T-group sessions have demonstrated value by using simple assessment techniques. Research on sensitivity training.[17] supports the positive effects of leadership training courses, and a well-developed assessment technique can be a fundamental element of leadership training. Crucially, learning a new assessment technique is a non-instantaneous process that develops over time through continuous practice and application, reinforcing the skills and increasing their effectiveness and impact on performance. These points lead to the formulation of the following Hypothesis 8:

Hypothesis 8: The agreement between the use of the assessment technique and the performance is more likely if its learning is nuanced and deep, rather than superficial, and continues over time.

Use in Language

A key characteristic of assessment techniques is the unique language and signs they create. Literature, including the works of Mead and Pierce[18], emphasizes the importance of signs and symbols for personal connection to a system and the process of inference[19]. The symbolic results of assessments are effective for quickly learning, recalling, and creating new inferences and skills. Assessment results come in various forms: narratives, traits with numbers, or typologies (e.g., MBTI's ESTJ or DISC's D, I, S, C). GRI's approach uses four factors to capture meaningful workplace behaviors. Once learned, this symbolic language enhances knowledge, communication, and decision-making. The conciseness, nuance, precision, memorability, and shareability of the results are critical, as they reduce ambiguity, improve decision-making, and boost the impact of other practical applications on performance. These observations allow for the formulation of the following Hypothesis 9:

Hypothesis 9: The agreement between the use of the assessment technique and the performance is more likely if the results and language created facilitate their practical use.

Causes of Use

The use of assessment techniques is influenced by several antecedent variables: the technique's properties, the user's qualities and interests, the organization's culture and social environment, and the publisher's business model. The properties of the technique and the publisher's business model are particularly crucial, as the technique's quality enables or limits its use, and the business model impacts deployment autonomy and resources. Individual and organizational beliefs about human nature can lead to resistance towards new assessment methods. However, these beliefs can change when confronted with practical results. Adaptive profiles can predict how an assessment method will be adopted within an organization regarding process, consensus, and speed. The environment and the people evolve as the method is implemented. These observations lead to the formulation of the following Hypothesis 10.

Hypothesis 10: The practical and theoretical use of the assessment technique is all the more probable if the assessment technique, publisher, environment, and individual user have appropriate characteristics.

Notes

- ↑ Zaltman, G, Pinson, C., Angelmar, R. (1973). Metatheory and Consumer Research, New York, Holt, Rinehart and Wintson.

- ↑ Mace G, Pétry F. (2000). Guide d’élaboration d’un projet de recherche en science sociales. DeBoeck Université.

The criteria of plausibility, verifiability, precision, generalization, and communicability are discussed in a separate note here. - ↑ Macy M. W., Willer R. (2002). From Factors to Actors: Computational Sociology and Agent-Based Modeling. Annual Review of Sociology, 28, 143-166.

Axtell, Robert L., and J. Doyne Farmer. 2025. "Agent-Based Modeling in Economics and Finance: Past, Present, and Future." Journal of Economic Literature 63 (1): 197–287. DOI: 10.1257/jel.20221319 - ↑ Alexander J. C., Giesen B., Münch R., Smelser N. (1987). The Micro-macro link. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- ↑ The items mentioned are only examples; the list continues. As mentioned, it was inspired both deductively, by literature in leadership, and inductively, by observation from the exploration field.

- ↑ Kouzes, J. M., & Posner, B. Z. (2023). The leadership challenge: How to make extraordinary things happen in organizations (7th ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

- ↑ Hersey, P., Blanchard, K. H., Jhonson, D. E. (1996). Management of organizational behavior. Utilizing human resources. Prentice Hall. 6th Edition. First published in 1969.

- ↑ Vroom, V. H., Jago A. G. (2007). The Role of the Situation in Leadership. American Psychologist. Vol. 62, No. 1, p. 17-24.

- ↑ Bass B. M. (1990). Bass and Stogdill’s Handbook of Leadership: theory, research, and managerial application. New York: Free Press.

- ↑ As for leadership, the list for recruitment is not limited to those items. These are just examples. The list continues.

- ↑ Möeller, H., and Kotte, S. (2022). “Assessment in coaching” in International handbook of evidence-based coaching: theory, research and practice. eds. S. Greif, H. Möller, W. Scholl, J. Passmore, and F. Müller (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 55–64.

Passmore, J. (Ed.). (2012). Psychometrics in coaching: Using psychological and psychometric tools for development (2nd ed.). Kogan Page. - ↑ Sutton, J. (2020) Coaching styles explained: 4 different approaches. Psychology.com. https://positivepsychology.com/coaching-styles/

- ↑ Passmore, J., & Tee, D. (2021). Coaching researched: A coaching psychology reader. John Wiley & Sons.

- ↑ Theeboom, T., Beersma, B., and van Vianen, A. E. (2014). Does coaching work? A meta-analysis on the effects of coaching on individual level outcomes in an organizational context. J. Posit. Psychol. 9, 1–18. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2013.837499

Cannon-Bowers, J. A., Bowers, C., Carlson, M., Doherty, P., Evans, S., & Hall, G. (2023). Workplace coaching: A meta-analysis and recommendations for advancing the science of coaching. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, Article 1204166. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1204166 - ↑ Lyra (2025). State of Workforce Mental Health Report. A report from Mental Health Innovation Summit 2025. https://www.lyrahealth.com/resources/report/2025-state-of-workforce-mental-health-report/

Kuang, T., Guo, C., Ren, M., Fu, L., Li, C., Ma, S., & Li, R. (2025). The effectiveness of e-mental health interventions on stress, anxiety, and depression symptoms in healthcare professionals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health, 25(1), 1083. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-024-02565-6 - ↑ World Health Organization. (2024, September 2). Mental health at work. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-at-work

- ↑ Ibid, Bass B. M. (1990)

- ↑ Mead G. H. (1934). Mind, Self and Society from the standpoint of a behaviorist. University of Chicago Press. Peirce, C. S. (1935) Philosophical Writings of Peirce. Selection of papers between 1931 and 1935 by J. S. Buchler New York, Dover Publications.

- ↑ Carnap, R. (1988). Meaning and Necessity. A study of Semantics and Modal Logic. The University of Chicago Press. 2nd Edition. First published in 1947.

Quine, W. V. (1960). Word and Object. The MIT Press.

Eco, U. (1979). A theory of Semiotics. Indiana University Press. Bloomington.

Eco, U. (1988). Le Signe. Histoire et analyse d'un concept. Editions Labor. Translate from: Segno, 1973.

Eco, U. (1995). The Search for the Perfect Language. Blackwell Publishers.

Hacking, I. (2001). Probability and Inductive Logic. Cambridge University Press.

Hacking, I. (2001). Why Language Matter To Philosophy? Cambridge University Press. 13th publication. First published in 1975.

Korzybski, A. (1933). Science and Sanity. Institute of General Semantics.

Hayakawa, S. I. (1939). Language in thought and action. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.