Understanding Signs: Difference between revisions

| (28 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

=Introduction= | =Introduction= | ||

Any signs created by assessment techniques, such as GRI’s adaptive profiles, and any other signs can be understood in three modes of existence and along three instances, which differentiate them from one another. This article details the nine constituents of a sign that’s derived from intersecting these different modes of existence and instances. It also introduces the 10 possible combinations of these elements, which illustrate how meaning builds on signs, what we can do with them, and the potential limitations inherent to their quality<ref>This synthesis on signs is an adaptation of Charles Pierce's work. See:<br/> | |||

Any signs, such as GRI’s adaptive profiles | Peirce, C. S. (1935) Philosophical Writings of Peirce. Selection of papers between 1931 and 1935 by J. S. Buchler New York, Dover Publications. First published under the title "The philosophy of Peirce Selected Writting", 1940.</ref>. | ||

=Generalities= | =Generalities= | ||

Signs can be | Signs can be understood in three modes of existence: | ||

The | [[File:Signs_Modes.png|right|200px]] | ||

* The '''quality''' of the sign, or phenomenon that we can perceive. | |||

* The '''facts, action''', occurrences, or events the signs stand for, and | |||

* The '''rules''', guiding principles, beliefs, and inferences that come with the sign. | |||

Additionally, signs have three instances: | |||

The | * The '''object''' that is represented by the sign, its fundamental basis, | ||

* The '''sign''' itself, and | |||

* The '''interpretant''', the physical person, who makes use of the sign. | |||

The three modes of existence can be intersected by the three instances. A sign can then be understood by the overlapping of these classifications, producing nine sub-categories that are shown below. | |||

[[File:Signs_Instances.png|center|700px]] | |||

=Facts= | =Qualities – First= | ||

The first mode of existence of a sign brings together the qualities of phenomena that each human being, equipped with their senses, is capable of revealing. Each time there is a phenomenon, there is a quality. Qualities are essential abstract potentialities. They do not have perfect identities, only partial similarities or identities, like colors or sounds from well-understood systems. If our experiences of them weren't so fragmented, there wouldn't be any sharp demarcation lines between them. The individual primary or secondary quality characteristics (see below) have this mode of existence. Any element that belongs to this mode of existence is called First. | |||

=Facts, Action – Second= | |||

The second mode of existence of phenomena includes actual facts or occurrences. Unlike primary qualities or elements, which are general and therefore somewhat vague and potential, an occurrence is quite individual; it occurs here and there. A permanent quality or fact is less purely individual. Insofar as it is actual, the permanence of this second mode of existence and its generalization consist only in being there at each moment taken separately. Qualities are concerned with facts, but do not create facts. Facts are about matters that are material substances. We do not see the facts as we see the qualities; i.e., they are not in the potentiality and in the essence of the facts. But we feel that the facts resist our will. That is why the facts can be called brutal. The essential qualities do not resist. It is the material that resists. In sensations, there is a reaction. But the essential qualities cannot, in fact, react. | The second mode of existence of phenomena includes actual facts or occurrences. Unlike primary qualities or elements, which are general and therefore somewhat vague and potential, an occurrence is quite individual; it occurs here and there. A permanent quality or fact is less purely individual. Insofar as it is actual, the permanence of this second mode of existence and its generalization consist only in being there at each moment taken separately. Qualities are concerned with facts, but do not create facts. Facts are about matters that are material substances. We do not see the facts as we see the qualities; i.e., they are not in the potentiality and in the essence of the facts. But we feel that the facts resist our will. That is why the facts can be called brutal. The essential qualities do not resist. It is the material that resists. In sensations, there is a reaction. But the essential qualities cannot, in fact, react. | ||

It is correct to say that we perceive matter immediately, ie, directly. To say that we infer matter only from its qualities is to say that we know the actual only from the potential. It would be a little less wrong to say that we know potential through the actual and only infer qualities by generalization from what we perceive in matter. Qualities are one element of phenomena, and facts, actions, and actualities are another. Facts and characteristics of achievement, as visualized by GRI adaptive profiles, belong to this mode of existence. Any element that belongs to this mode of existence is called Second. | It is correct to say that we perceive matter immediately, ie, directly. To say that we infer matter only from its qualities is to say that we know the actual only from the potential. It would be a little less wrong to say that we know potential through the actual and only infer qualities by generalization from what we perceive in matter. Qualities are one element of phenomena, and facts, actions, and actualities are another. Facts and characteristics of achievement, as visualized by GRI adaptive profiles, belong to this mode of existence. Any element that belongs to this mode of existence is called Second. | ||

=Rules= | =Rules – Third= | ||

The third mode of existence of the elements of phenomena consists of rules when we look at them from the outside. When we look at both sides of their mode of existence, inside and outside, we call them thoughts. Rules are neither qualities nor facts. They are not qualities because they can be produced and grow, whereas a quality (First Element) is eternal, independent of time and of any achievements. Moreover, rules can have good or bad reasons. But asking why a quality is what it is, why red is red and not green, leads nowhere. If red were green, it wouldn't be red. | The third mode of existence of the elements of phenomena consists of rules when we look at them from the outside. When we look at both sides of their mode of existence, inside and outside, we call them thoughts. Rules are neither qualities nor facts. They are not qualities because they can be produced and grow, whereas a quality (First Element) is eternal, independent of time and of any achievements. Moreover, rules can have good or bad reasons. But asking why a quality is what it is, why red is red and not green, leads nowhere. If red were green, it wouldn't be red. | ||

| Line 26: | Line 35: | ||

The interpretant as a Third element is also a sign capable of being interpreted again, and so on indefinitely. This process constitutes the semiotic process, which is an active and continuous process, because from a sign it is possible to mentally represent another sign, giving rise to other interpretants, and this continues until the real exhaustion of the process of exchange or thought. Thinking and meaning are therefore the same process called semiosis, seen from two different angles. | The interpretant as a Third element is also a sign capable of being interpreted again, and so on indefinitely. This process constitutes the semiotic process, which is an active and continuous process, because from a sign it is possible to mentally represent another sign, giving rise to other interpretants, and this continues until the real exhaustion of the process of exchange or thought. Thinking and meaning are therefore the same process called semiosis, seen from two different angles. | ||

=The Object | =The Object= | ||

In the first group of signs, by maintaining a relationship with its object or foundation, the sign can be in itself a quality and exist effectively (qualisign), be in action, act, or behave (sinsign), or be a general law (legisign). | In the first group of signs, by maintaining a relationship with its object or foundation, the sign can be in itself a quality and exist effectively (qualisign), be in action, act, or behave (sinsign), or be a general law (legisign). | ||

==Qualisign== | ==Qualisign== | ||

A qualisign is a quality that is a sign, with significant character. It cannot act as a sign until it is part of something else, but being part of something else has nothing to do with its sign characteristic. It can be an individual characteristic, the | A qualisign is a quality that is a sign, with significant character. It cannot act as a sign until it is part of something else, but being part of something else has nothing to do with its sign characteristic. It can be an individual characteristic, the representation of an activity, or an activity report. | ||

==Sinsign== | ==Sinsign== | ||

| Line 36: | Line 45: | ||

==Legisign== | ==Legisign== | ||

A legisign is | A legisign is a sign that is not unique to a single individual, but is general or conventional, has received some approval, social or cultural value, and is potentially significant as a rule, norm, or law. Each legisign signifies something through an occurrence of its application, which is called its replica. | ||

The expression "math | The expression "being a math genius" is a legisign by the potential meaning it carries. Written here in black on white on this page, but in red, this expression bears the same legisign regardless of the color of the ink. The expression written on this page is a sinsign. Each occurrence of this legisign is a replica. | ||

Each legisign requires sinsigns. But the sinsigns are not necessarily ordinary sinsigns, such as the particular occurrences of the expression "math | Each legisign requires sinsigns. But the sinsigns are not necessarily ordinary sinsigns, such as the particular occurrences of the expression "being a math genius" appearing black on white, which are regarded as significant. A badge or a replica cannot be significant except for the laws, rules, or social values that make it so. | ||

Cultural or corporate | Cultural or corporate values, norms, and rules of behavior associated with the use of an assessment technique are legisigns. They have potential meaning. The writing of these rules in a booklet or their summary on a poster is a sinsign. The quality of these objects, regardless of their involvement and use are qualisigns. | ||

=The Sign | =The Sign= | ||

In the second group, the sign maintains a relationship with its object, which may consist of the sign possessing a character as such (icon), or possessing an existential relationship with the object (index), or possessing a conventional relationship with the interpretant (symbol). Depending on their relationship to their object, these signs can take on different aspects. The icon can be an image, a diagram, or a metaphor. The index can be genuine or degenerate. This classification does not define types of signs but semiotic categories that combine general and abstract types. | In the second group, the sign maintains a relationship with its object, which may consist of the sign possessing a character as such (icon), or possessing an existential relationship with the object (index), or possessing a conventional relationship with the interpretant (symbol). Depending on their relationship to their object, these signs can take on different aspects. The icon can be an image, a diagram, or a metaphor. The index can be genuine or degenerate. This classification does not define types of signs but semiotic categories that combine general and abstract types. | ||

| Line 87: | Line 96: | ||

It is only through symbols that new symbols can grow. A symbol, once it exists, spreads through a social group. In use and experience, its meaning grows: words such as strength, intelligence, personality, law, welfare, and manager mean very different things to us than our ancestors. | It is only through symbols that new symbols can grow. A symbol, once it exists, spreads through a social group. In use and experience, its meaning grows: words such as strength, intelligence, personality, law, welfare, and manager mean very different things to us than our ancestors. | ||

=The Interpretant | =The Interpretant= | ||

In this third group, the sign can represent for the interpretant a possibility (rheme), be linked to a fact (decisign), or represent a convention or a law (argument). | In this third group, the sign can represent for the interpretant a possibility (rheme), be linked to a fact (decisign), or represent a convention or a law (argument). | ||

==Rheme== | |||

A rheme is a sign which, for its interpreter, is a sign assuming a possibility of qualities. That is to say that for its interpretant, it is understood as representing this or that sort of possible object. Any rheme can contain information, but the rheme is not interpreted as accomplishing this. | A rheme is a sign which, for its interpreter, is a sign assuming a possibility of qualities. That is to say that for its interpretant, it is understood as representing this or that sort of possible object. Any rheme can contain information, but the rheme is not interpreted as accomplishing this. | ||

==Decisign== | |||

A decisign is a sign which, for its interpreter, is an actual sign of existence. It cannot, therefore, be an icon, because the icon does not allow the decisign to be interpreted as referring to something that currently exists. A decisign necessarily implies constituting a rheme, to describe the fact that it is interpreted as indicating. But this is a special case of rheme; and while it is essential to the decisign, it does not in any way constitute it. | A decisign is a sign which, for its interpreter, is an actual sign of existence. It cannot, therefore, be an icon, because the icon does not allow the decisign to be interpreted as referring to something that currently exists. A decisign necessarily implies constituting a rheme, to describe the fact that it is interpreted as indicating. But this is a special case of rheme; and while it is essential to the decisign, it does not in any way constitute it. | ||

==Argument== | |||

An argument is a sign which, for its interpreter, is a sign of law or rule. A rheme can be said to be a sign which, from the point of view of the interpretant, is understood to represent its object mainly because of its characteristics; that a decisign is a sign, which from the point of view of the interpretant is understood as its object by virtue of its actual existence; and that an argument is a sign which, from the point of view of the interpretant, is understood to represent its object by virtue of its character as a sign. | An argument is a sign which, for its interpreter, is a sign of law or rule. A rheme can be said to be a sign which, from the point of view of the interpretant, is understood to represent its object mainly because of its characteristics; that a decisign is a sign, which from the point of view of the interpretant is understood as its object by virtue of its actual existence; and that an argument is a sign which, from the point of view of the interpretant, is understood to represent its object by virtue of its character as a sign. | ||

| Line 102: | Line 111: | ||

=10 Categories of a Sign= | =10 Categories of a Sign= | ||

[[File:Signs_9 modes.png|center|700px]] | |||

Since the sign can exist only through a complex of relations between the three instances (object, sign itself, interpretant), it is then necessarily found as covering a qualisign, sinsign, or legisign quality; together with an iconic, indexical, or symbolic quality; and at the same time as a rheme, desisign, or argument quality. This leads to a maximum of 10 possible combinations of the nine categories as it s now explained. | Since the sign can exist only through a complex of relations between the three instances (object, sign itself, interpretant), it is then necessarily found as covering a qualisign, sinsign, or legisign quality; together with an iconic, indexical, or symbolic quality; and at the same time as a rheme, desisign, or argument quality. This leads to a maximum of 10 possible combinations of the nine categories as it s now explained. | ||

A qualisign is necessarily iconic and rhematic; it cannot take on the quality of facts or rules at the level of the sign itself and of the interpretant. A sinsign can be iconic and indexical, but it cannot take on the | A qualisign is necessarily iconic and rhematic; it cannot take on the quality of facts or rules at the level of the sign itself and of the interpretant. A sinsign can be iconic and indexical, but it cannot take on the qualities of a rule and therefore be symbolic. A legisign can be iconic, indexical and symbolic; it can also be rhematic, designic, and argumentative. Only one combination concerns the qualisign, three combinations concern the sinsign, and six combinations concern the legisign. Moreover, an argument can only be a symbol and legisign. Only one combination, therefore, concerns the argument. | ||

The combinations are fundamental to understanding the difference between the signs as such and their uses by conventional or individual rules. They also make it possible to | The combinations are numbered from 1 to 10. The numbering starts from a potentially present quality, as a generic characteristic (qualisign, icon, rheme) and extends to a value-laden sign processed by its interpretant (legisign, symbol, argument). The combinations are fundamental to understanding the difference between the signs as such and their uses by conventional or individual rules. They also make it possible to trace the genesis of meaning in a sign and to see how signs, as such, designate the qualities, behaviors, actions, or roles of people and organizations. | ||

The ten combinations associating the three modes of existence with the three instances of foundation, sign as such, and interpreting are specified below. | The ten combinations associating the three modes of existence with the three instances of foundation, sign as such, and interpreting are specified below. | ||

{| class="wikitable" style="margin: auto;" | {| class="wikitable" style="margin: auto;" | ||

! | ! # !! Designation !! Example !! Sign | ||

|- | |- | ||

| 1 || The | | 1 || Qualisign, (Iconic, Rhematic)|| The perception of the color red as a sign of the generic essence "red" or of an individual characteristic, such as a skill of a specific domain, as a general sign of skill in the domain. || [[File:Signs_1.png|center|80px]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| 2 || | | 2 || Sinsign, Iconic, (Rhematic) || Any triangle representing the geometric entity “triangle” or a GRI adaptive profile as a general representation of profiles representing social behavior. || [[File:Signs_2.png|center|80px]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| 3 || | | 3 || Sinsign, Indexical, Rhematic || A spontaneous loud cry that draws attention to an object that’s causing it; A characteristic highlighted on a resume or social media. || [[File:Signs_3.png|center|80px]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| 4 || | | 4 || Sinsign, Indexical, Decisign. || A flag on the beach provides factual information such as "the wind is blowing from the east", by virtue of a causal connection with the physical phenomenon; or the adaptive profile that indicates the direction of action, such as being proactive or reactive, engaged or disengaged. || [[File:Signs_4.png|center|80px]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| 5 || | | 5 || Legisign, Iconic, (Rhematic) || This sign is a general rule or type. Its mode of existence is that of governing replicas of type 2 above. Example: a diagram as an abstract law, such as the Pythagorean triangle, a GRI profile for a position, or any other characteristic defined for a position. || [[File:Signs_5.png|center|80px]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| 6 || | | 6 || Legisign, Indexical, Rhematic. || This sign is an already established rule or general type, which draws attention to its object. Such a sign requires proximity to the object. Example: a demonstrative pronoun like "this one"; hence the use of “this one” with a noun like “this person”. A person's GRI adaptive profile, as such, falls into this category as potentially designating a person’s social behavior. Any replica of such a sign is a rhematic indexical sinsign (Combination 3 above). || [[File:Signs_6.png|center|80px]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| 7 || | | 7 || Legisign, Indexical, Decisign || It is an already established rule or general type that provides guidance about the object it designates. Its task is to distinguish the real presence of an object, usually and abstractly represented by a Rheme. Example: the cry of someone: “Hey there!”, or the answer "it's Alexandre", to the question "But who best represents this person, this GRI adaptive profile, or these traits?" This sign involves the use of an Iconic Legisigne (combination 3 above) to signify information and a Rhematic Indexical Legisigne (combination 6 above) to denote the subject of the information. The replica of this sign is a Sinsign Dicent (Combination 4 above). || [[File:Signs_7.png|center|80px]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| 8 || The | | 8 || (Legisignique), Symbol, Rhematic || This sign is associated with its object by an idea or a concept of a general nature. Example: a common name, a general term such as a GRI reference profile, or a typology. The replica of such a sign is a Rhematic Indexical Sign (Combination 3), which suggests an image to the mind. || [[File:Signs_8.png|center|80px]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| 9 || | | 9 || (Legisignique), Symbol, Decisign. || This combination is an ordinary proposition that connects the sign to its object by a general idea. Unlike the previous combination 8, the interpreter represents the sign in such a way that the rule that comes to mind must be connected with the object indicated. Example: a proposition with an abstract existence, such as “the cat is black”, or “this skill is current”, or “This GRI adaptive profile is wide”. Its replica is a Sinsign, Indexical, Decisign (combination 4) when the information conveyed is a current fact or when the rule it conveys is pending. || [[File:Signs_9.png|center|80px]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| 10 || | | 10 || (Legisignique, Symbolic), Argument || This combination is a sign whose interpretant represents the object as being a later sign of a rule such that this rule, which passes from such a premise to such a conclusion, tends to be true. Its object is general. This sign is the abstract form of the syllogism. Its replica is a sinsign, indexical Decisign (combination 4). || [[File:Signs_10.png|center|80px]] | ||

|} | |} | ||

=Building Sense on the Adaptive Profiles= | |||

Building Sense on the Adaptive Profiles | |||

The semiosis for the adaptive profile can be understood with the 10 combinations of instances and modes of existence of the sign. The 10 combinations make it possible to follow the genesis of the construction of meaning by the interpreter on the profiles. | The semiosis for the adaptive profile can be understood with the 10 combinations of instances and modes of existence of the sign. The 10 combinations make it possible to follow the genesis of the construction of meaning by the interpreter on the profiles. | ||

[[File:Signs_9 modes_Illustrated.png|center| | [[File:Signs_9 modes_Illustrated 4.png|center|700px]] | ||

{| class="wikitable" style="margin: auto;" | {| class="wikitable" style="margin: auto;" | ||

! Combination !! Meaning !! Sign | ! Combination !! Meaning !! Sign | ||

|- | |- | ||

| 1 || The | | 1 || The adaptive profile is potentially present and general. The measure exists because of the history of the technique, including within the organization and its employees, who can both be considered as processes of symbol production. || [[File:Signs_1.png|center|80px]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| 2 || The | | 2 || The adaptive profile takes on a potential value, indicative of something related to action. || [[File:Signs_2.png|center|80px]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| 3 || The | | 3 || The adaptive profile is positioned in a context, in connection with a job or other people, a problem to solve, or situation to optimize. || [[File:Signs_3.png|center|80px]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| 4 || The | | 4 || The adaptive profile gives a direction of potential action for the person who interprets it, without being a rule. || [[File:Signs_4.png|center|80px]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| 5 || The | | 5 || The adaptive profile takes on a potential rule value; this is the case after the profile is potentially present, taught, or explained and learned. || [[File:Signs_5.png|center|80px]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| 6 || The | | 6 || The adaptive profile attracts the attention of the interpreter. || [[File:Signs_6.png|center|80px]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| 7 || The | | 7 || The adaptive profile’s information is perceived by the interpretant who is in a position to interpret it. || [[File:Signs_7.png|center|80px]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| 8 || The | | 8 || The adaptive profile conveys meaning to the interpretant through a general idea. || [[File:Signs_8.png|center|80px]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| 9 || The | | 9 || The adaptive profile is potentially interpretable by its user. The applicable rule is connected to the sign to which it relates. || [[File:Signs_9.png|center|80px]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| 10 || The | | 10 || The adaptive profile is used in the semiotic process. || [[File:Signs_10.png|center|80px]] | ||

|} | |} | ||

=Notes= | =Notes= | ||

[[Category:General Framework]] | [[Category:General Framework]] | ||

Latest revision as of 01:08, 12 November 2025

Introduction

Any signs created by assessment techniques, such as GRI’s adaptive profiles, and any other signs can be understood in three modes of existence and along three instances, which differentiate them from one another. This article details the nine constituents of a sign that’s derived from intersecting these different modes of existence and instances. It also introduces the 10 possible combinations of these elements, which illustrate how meaning builds on signs, what we can do with them, and the potential limitations inherent to their quality[1].

Generalities

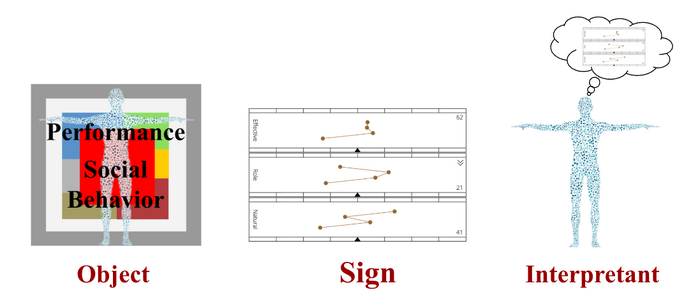

Signs can be understood in three modes of existence:

- The quality of the sign, or phenomenon that we can perceive.

- The facts, action, occurrences, or events the signs stand for, and

- The rules, guiding principles, beliefs, and inferences that come with the sign.

Additionally, signs have three instances:

- The object that is represented by the sign, its fundamental basis,

- The sign itself, and

- The interpretant, the physical person, who makes use of the sign.

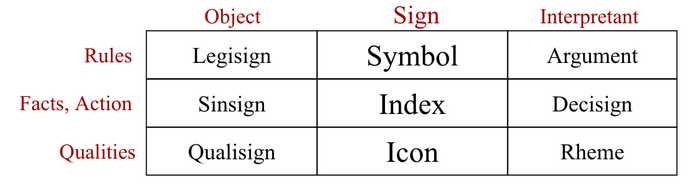

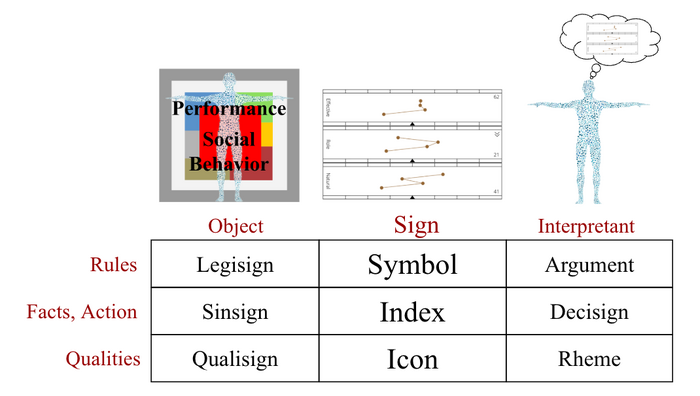

The three modes of existence can be intersected by the three instances. A sign can then be understood by the overlapping of these classifications, producing nine sub-categories that are shown below.

Qualities – First

The first mode of existence of a sign brings together the qualities of phenomena that each human being, equipped with their senses, is capable of revealing. Each time there is a phenomenon, there is a quality. Qualities are essential abstract potentialities. They do not have perfect identities, only partial similarities or identities, like colors or sounds from well-understood systems. If our experiences of them weren't so fragmented, there wouldn't be any sharp demarcation lines between them. The individual primary or secondary quality characteristics (see below) have this mode of existence. Any element that belongs to this mode of existence is called First.

Facts, Action – Second

The second mode of existence of phenomena includes actual facts or occurrences. Unlike primary qualities or elements, which are general and therefore somewhat vague and potential, an occurrence is quite individual; it occurs here and there. A permanent quality or fact is less purely individual. Insofar as it is actual, the permanence of this second mode of existence and its generalization consist only in being there at each moment taken separately. Qualities are concerned with facts, but do not create facts. Facts are about matters that are material substances. We do not see the facts as we see the qualities; i.e., they are not in the potentiality and in the essence of the facts. But we feel that the facts resist our will. That is why the facts can be called brutal. The essential qualities do not resist. It is the material that resists. In sensations, there is a reaction. But the essential qualities cannot, in fact, react.

It is correct to say that we perceive matter immediately, ie, directly. To say that we infer matter only from its qualities is to say that we know the actual only from the potential. It would be a little less wrong to say that we know potential through the actual and only infer qualities by generalization from what we perceive in matter. Qualities are one element of phenomena, and facts, actions, and actualities are another. Facts and characteristics of achievement, as visualized by GRI adaptive profiles, belong to this mode of existence. Any element that belongs to this mode of existence is called Second.

Rules – Third

The third mode of existence of the elements of phenomena consists of rules when we look at them from the outside. When we look at both sides of their mode of existence, inside and outside, we call them thoughts. Rules are neither qualities nor facts. They are not qualities because they can be produced and grow, whereas a quality (First Element) is eternal, independent of time and of any achievements. Moreover, rules can have good or bad reasons. But asking why a quality is what it is, why red is red and not green, leads nowhere. If red were green, it wouldn't be red.

A rule is general in referring to all possible things and not primarily to those which in fact exist. A collection of facts (Secondary elements) cannot constitute a rule, because the rule goes beyond the facts accomplished individually and determines how the facts could be, but not all could have occurred or will occur. The rule is a "general fact" if the general aspect has a combination of potentiality in it, so that no conjunction of actions here and now can ever fabricate a general fact.

The rule or "general fact" concerns the potential world of qualities, whereas a fact concerns the actual world. In the same way that action requires a particular type of subject, which is matter, the rule requires a particular type of subject, which is thought, as a subject distant from any individual action. The rule is therefore something as distant from quality and action as these two are distant from each other. Any element that belongs to this third mode of existence is called the Third.

The interpretant as a Third element is also a sign capable of being interpreted again, and so on indefinitely. This process constitutes the semiotic process, which is an active and continuous process, because from a sign it is possible to mentally represent another sign, giving rise to other interpretants, and this continues until the real exhaustion of the process of exchange or thought. Thinking and meaning are therefore the same process called semiosis, seen from two different angles.

The Object

In the first group of signs, by maintaining a relationship with its object or foundation, the sign can be in itself a quality and exist effectively (qualisign), be in action, act, or behave (sinsign), or be a general law (legisign).

Qualisign

A qualisign is a quality that is a sign, with significant character. It cannot act as a sign until it is part of something else, but being part of something else has nothing to do with its sign characteristic. It can be an individual characteristic, the representation of an activity, or an activity report.

Sinsign

A sinsign is an occurrence, a fact, an event endowed with a real existence, which is also a sign. It can only be such by virtue of its qualities and therefore implies one or more qualisigns.

Legisign

A legisign is a sign that is not unique to a single individual, but is general or conventional, has received some approval, social or cultural value, and is potentially significant as a rule, norm, or law. Each legisign signifies something through an occurrence of its application, which is called its replica.

The expression "being a math genius" is a legisign by the potential meaning it carries. Written here in black on white on this page, but in red, this expression bears the same legisign regardless of the color of the ink. The expression written on this page is a sinsign. Each occurrence of this legisign is a replica.

Each legisign requires sinsigns. But the sinsigns are not necessarily ordinary sinsigns, such as the particular occurrences of the expression "being a math genius" appearing black on white, which are regarded as significant. A badge or a replica cannot be significant except for the laws, rules, or social values that make it so.

Cultural or corporate values, norms, and rules of behavior associated with the use of an assessment technique are legisigns. They have potential meaning. The writing of these rules in a booklet or their summary on a poster is a sinsign. The quality of these objects, regardless of their involvement and use are qualisigns.

The Sign

In the second group, the sign maintains a relationship with its object, which may consist of the sign possessing a character as such (icon), or possessing an existential relationship with the object (index), or possessing a conventional relationship with the interpretant (symbol). Depending on their relationship to their object, these signs can take on different aspects. The icon can be an image, a diagram, or a metaphor. The index can be genuine or degenerate. This classification does not define types of signs but semiotic categories that combine general and abstract types.

Icon

The icon is an image of its object and can only strictly be an idea for the interpreter. A sign is iconic by representing its object essentially by its similarity, regardless of its mode of existence. Strictly speaking, even an idea cannot be an icon except in the sense of a possibility. A possibility alone is an icon purely by virtue of its quality, and its object can only assume a First character.

Any material image, such as a painting, in itself, without a caption or without label, by its qualities, is an iconic representation. An icon can also be a diagram, in which essentially dyadic relations, or relations seen as such, can be established by analogy between its parts and those of a thing.

Icons that establish a representative character by parallelism with something else are metaphors. The likely quality of an icon can be helped by convention rules. In fact, an algebraic formula is an icon, made such by the rules of commutation, association, and distribution of symbols; or even clothing in a white coat or a blue coat made iconic due to the rule of use in offices or workshops.

The icon is the only medium for directly communicating an idea. Any indirect method of communicating an idea depends on the use of an icon for its establishment. Every assertion contains an icon or a set of icons, or else contains signs whose meaning can only be explained by icons. The idea that the set of icons (or the equivalent of a set of icons) contained in an assertion has a meaning is called the predicate of the assertion. One of the characteristic properties of the icon is that by its direct observation, other truths concerning this object can be distinguished from those which suffice to determine its construction.

The results produced by the tests, whether graphs, spider charts, series of letters, histograms, or even reports, are icons because of the resemblances they have to the parts that constitute them and the comparisons, associations that they make it possible to establish whether or not these icons correspond to the people to whom they refer.

Index

An index is a sign, or representation, which refers to its object not so much because of its resemblances or analogies with it, nor because of its association with general characteristics that this object possesses, but because of its dynamic relationship (including spatial and temporal aspects) both on the one hand with the individual object and on the other hand with the sensation or memory of the person for whom they serve as a sign.

Indexes can be distinguished from other signs or representations by three characteristics: first, they bear no significant resemblance to their objects; second, they refer to individuals, single units, single collections of units, or a single continuum; third, they direct attention to objects blindly, unconsciously, or automatically.

It is difficult, if not impossible, to give an example of a pure index or to find any sign devoid of indexical quality. Psychologically, the action of indexes depends on an association of contiguity and not on an association of resemblance or an intellectual operation.

The index is a representation whose representative character consists of being a Second characteristic. If the Second characteristic is an existence relation, the index is "pure". If the Second characteristic is a reference, the index is degenerated. A pure index and its object must have the characteristic of existence, be it things or facts, and its immediate interpretant must have this same characteristic. But since any feature must contain a character, it follows that an index contains an icon.

Icons and indexes do not assert anything. If an icon must be interpreted by a sentence, this sentence is in a "potential tendency", ie, it simply says, for example: "Suppose that a figure has three sides". If an index is to be interpreted this way, the trend is imperative, or exclamatory, such as "Look here!".

Symbol

A symbol is a conventional sign, depending on an acquired or innate habit. It is a representation whose representative character consists of being a rule that will determine its interpretant. All words, phrases, books, articles, and other conventional signs are symbols.

We write or pronounce the word "human", but it is only a replica that is pronounced or written. The word itself only has reality in the fact that there exist facts or objects which conform to it. It is a generally acquired way of making five sounds or representations of sounds succeed each other: h-u-m-a-n, which becomes a sign only by the fact that a habit, or acquired law, causes a cue to be interpreted as signifying a human being. The word “human” and its meanings both have general rules. But the word alone, without the meaning, prescribes the self-replicating qualities.

A symbol is a law, a rule, a regularity of an indefinite future. Its interpretant must have the same description, and the complete immediate object, or its meaning must be of the same nature. A law necessarily governs, or is embodied in the characteristics, and prescribes some of its qualities.

A pure symbol is a symbol that has a general meaning. There are two types of degenerate symbols: the singular symbol, whose object is an existing characteristic and which signifies only the characters that this characteristic can realize; and an abstract symbol, whose only object is a character.

There is a regular progression in the three orders of the sign as icon, index, or symbol. The icon has no dynamic relationship with the object it represents; the fact is that its qualities resemble those of the object and excite sensations in the mind of whom it is similar. But the icon is not connected to these qualities. The index is physically connected to its object; they both form an organic pair, but the interpreting mind has nothing to do with this connection except noticing it once it is established. The symbol is connected to its object because of the idea of the symbol-acting-on-the-mind, without which such a connection could not exist. Each intellectual operation involves a triad of signs.

A symbol cannot indicate a particular thing; it denotes some kind of thing. He himself is a kind of thing and not a single thing. A person can write the word "star", but that does not make that person the creator of the word star, even if the person erases the word. The word lives on in the minds of those who use it. Even asleep, it exists in their memory. And so we can admit that the words are general.

The symbols grow. They come into existence by the development of other signs, particularly through icons, or through a mixture of signs of the nature of icons or symbols. One thinks only in signs, and these mental signs are of a mixed nature; their symbolic parts are called concepts.

It is only through symbols that new symbols can grow. A symbol, once it exists, spreads through a social group. In use and experience, its meaning grows: words such as strength, intelligence, personality, law, welfare, and manager mean very different things to us than our ancestors.

The Interpretant

In this third group, the sign can represent for the interpretant a possibility (rheme), be linked to a fact (decisign), or represent a convention or a law (argument).

Rheme

A rheme is a sign which, for its interpreter, is a sign assuming a possibility of qualities. That is to say that for its interpretant, it is understood as representing this or that sort of possible object. Any rheme can contain information, but the rheme is not interpreted as accomplishing this.

Decisign

A decisign is a sign which, for its interpreter, is an actual sign of existence. It cannot, therefore, be an icon, because the icon does not allow the decisign to be interpreted as referring to something that currently exists. A decisign necessarily implies constituting a rheme, to describe the fact that it is interpreted as indicating. But this is a special case of rheme; and while it is essential to the decisign, it does not in any way constitute it.

Argument

An argument is a sign which, for its interpreter, is a sign of law or rule. A rheme can be said to be a sign which, from the point of view of the interpretant, is understood to represent its object mainly because of its characteristics; that a decisign is a sign, which from the point of view of the interpretant is understood as its object by virtue of its actual existence; and that an argument is a sign which, from the point of view of the interpretant, is understood to represent its object by virtue of its character as a sign.

In relation to argument, judgment can be seen as a mental act by which the person judging seeks to impress himself on the truth of his proposition. It's a bit like trying to convince someone of something, except that the judgment is about the person themselves. One can wonder about the nature of judgment in matters of logic. In logic, we are not concerned with the psychological nature of the act of judgment. The question concerns the nature of a particular kind of sign called a proposition, which is the matter on which the act of judgment is exercised. The proposition itself retains its full meaning whether or not it is expressed by the interpretant. Its particularity lies in its relationship with its performer.

10 Categories of a Sign

Since the sign can exist only through a complex of relations between the three instances (object, sign itself, interpretant), it is then necessarily found as covering a qualisign, sinsign, or legisign quality; together with an iconic, indexical, or symbolic quality; and at the same time as a rheme, desisign, or argument quality. This leads to a maximum of 10 possible combinations of the nine categories as it s now explained.

A qualisign is necessarily iconic and rhematic; it cannot take on the quality of facts or rules at the level of the sign itself and of the interpretant. A sinsign can be iconic and indexical, but it cannot take on the qualities of a rule and therefore be symbolic. A legisign can be iconic, indexical and symbolic; it can also be rhematic, designic, and argumentative. Only one combination concerns the qualisign, three combinations concern the sinsign, and six combinations concern the legisign. Moreover, an argument can only be a symbol and legisign. Only one combination, therefore, concerns the argument.

The combinations are numbered from 1 to 10. The numbering starts from a potentially present quality, as a generic characteristic (qualisign, icon, rheme) and extends to a value-laden sign processed by its interpretant (legisign, symbol, argument). The combinations are fundamental to understanding the difference between the signs as such and their uses by conventional or individual rules. They also make it possible to trace the genesis of meaning in a sign and to see how signs, as such, designate the qualities, behaviors, actions, or roles of people and organizations.

The ten combinations associating the three modes of existence with the three instances of foundation, sign as such, and interpreting are specified below.

| # | Designation | Example | Sign |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Qualisign, (Iconic, Rhematic) | The perception of the color red as a sign of the generic essence "red" or of an individual characteristic, such as a skill of a specific domain, as a general sign of skill in the domain. | |

| 2 | Sinsign, Iconic, (Rhematic) | Any triangle representing the geometric entity “triangle” or a GRI adaptive profile as a general representation of profiles representing social behavior. | |

| 3 | Sinsign, Indexical, Rhematic | A spontaneous loud cry that draws attention to an object that’s causing it; A characteristic highlighted on a resume or social media. | |

| 4 | Sinsign, Indexical, Decisign. | A flag on the beach provides factual information such as "the wind is blowing from the east", by virtue of a causal connection with the physical phenomenon; or the adaptive profile that indicates the direction of action, such as being proactive or reactive, engaged or disengaged. | |

| 5 | Legisign, Iconic, (Rhematic) | This sign is a general rule or type. Its mode of existence is that of governing replicas of type 2 above. Example: a diagram as an abstract law, such as the Pythagorean triangle, a GRI profile for a position, or any other characteristic defined for a position. | |

| 6 | Legisign, Indexical, Rhematic. | This sign is an already established rule or general type, which draws attention to its object. Such a sign requires proximity to the object. Example: a demonstrative pronoun like "this one"; hence the use of “this one” with a noun like “this person”. A person's GRI adaptive profile, as such, falls into this category as potentially designating a person’s social behavior. Any replica of such a sign is a rhematic indexical sinsign (Combination 3 above). | |

| 7 | Legisign, Indexical, Decisign | It is an already established rule or general type that provides guidance about the object it designates. Its task is to distinguish the real presence of an object, usually and abstractly represented by a Rheme. Example: the cry of someone: “Hey there!”, or the answer "it's Alexandre", to the question "But who best represents this person, this GRI adaptive profile, or these traits?" This sign involves the use of an Iconic Legisigne (combination 3 above) to signify information and a Rhematic Indexical Legisigne (combination 6 above) to denote the subject of the information. The replica of this sign is a Sinsign Dicent (Combination 4 above). | |

| 8 | (Legisignique), Symbol, Rhematic | This sign is associated with its object by an idea or a concept of a general nature. Example: a common name, a general term such as a GRI reference profile, or a typology. The replica of such a sign is a Rhematic Indexical Sign (Combination 3), which suggests an image to the mind. | |

| 9 | (Legisignique), Symbol, Decisign. | This combination is an ordinary proposition that connects the sign to its object by a general idea. Unlike the previous combination 8, the interpreter represents the sign in such a way that the rule that comes to mind must be connected with the object indicated. Example: a proposition with an abstract existence, such as “the cat is black”, or “this skill is current”, or “This GRI adaptive profile is wide”. Its replica is a Sinsign, Indexical, Decisign (combination 4) when the information conveyed is a current fact or when the rule it conveys is pending. | |

| 10 | (Legisignique, Symbolic), Argument | This combination is a sign whose interpretant represents the object as being a later sign of a rule such that this rule, which passes from such a premise to such a conclusion, tends to be true. Its object is general. This sign is the abstract form of the syllogism. Its replica is a sinsign, indexical Decisign (combination 4). |

Building Sense on the Adaptive Profiles

The semiosis for the adaptive profile can be understood with the 10 combinations of instances and modes of existence of the sign. The 10 combinations make it possible to follow the genesis of the construction of meaning by the interpreter on the profiles.

| Combination | Meaning | Sign |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | The adaptive profile is potentially present and general. The measure exists because of the history of the technique, including within the organization and its employees, who can both be considered as processes of symbol production. | |

| 2 | The adaptive profile takes on a potential value, indicative of something related to action. | |

| 3 | The adaptive profile is positioned in a context, in connection with a job or other people, a problem to solve, or situation to optimize. | |

| 4 | The adaptive profile gives a direction of potential action for the person who interprets it, without being a rule. | |

| 5 | The adaptive profile takes on a potential rule value; this is the case after the profile is potentially present, taught, or explained and learned. | |

| 6 | The adaptive profile attracts the attention of the interpreter. | |

| 7 | The adaptive profile’s information is perceived by the interpretant who is in a position to interpret it. | |

| 8 | The adaptive profile conveys meaning to the interpretant through a general idea. | |

| 9 | The adaptive profile is potentially interpretable by its user. The applicable rule is connected to the sign to which it relates. | |

| 10 | The adaptive profile is used in the semiotic process. |

Notes

- ↑ This synthesis on signs is an adaptation of Charles Pierce's work. See:

Peirce, C. S. (1935) Philosophical Writings of Peirce. Selection of papers between 1931 and 1935 by J. S. Buchler New York, Dover Publications. First published under the title "The philosophy of Peirce Selected Writting", 1940.