Three Competing Models: Difference between revisions

(Created page with "=Introduction= For decades, researchers and the personality assessment industry have explored and refined various techniques for measuring personality in organizations. These techniques have been employed for recruitment, personal development, coaching, and more, and in clinical settings as well. We have examined these techniques at GRI by looking at their effects and benefits on individual and organizational performance, how they were developed, and by studying their u...") |

m (→Introduction) |

||

| (39 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

=Introduction= | =Introduction= | ||

For decades, researchers and the personality assessment industry have | [[File:Three models.png|right|250px]]For decades, researchers and the personality assessment industry have studied and refined various methods for measuring personality in organizations. These methods are used for hiring, personal development, coaching, and more, including in clinical settings. We at GRI have reviewed these methods by analyzing their effects and benefits on individual and organizational performance, how they were developed, and by studying their users: traditional users like human resources managers, recruiters, coaches, and clinicians, as well as managers and executives. | ||

We have | |||

In social matters, unlike in technology, as the history of assessment techniques shows, understanding their true potential develops slowly. This extended process may be due to a combination of factors: the abstract nature of the concepts being measured, the effort needed to learn these techniques, and the emotional attachment people develop toward them. | |||

In social matters, unlike in technology, as the history of assessment techniques shows, understanding their true potential | |||

Assessment techniques can reveal their real capabilities through actual cases that genuinely matter. These cases usually come from organizations that care not only about performance in finance and production but also about how these outcomes are delivered from behavioral, cognitive, and emotional perspectives. | |||

Assessment techniques can reveal their | |||

Using both qualitative and quantitative methods has helped us gain a detailed understanding of assessment techniques' capabilities and limitations: what they truly measure, how these measures are represented and used, and the questions they seek to answer. These topics are discussed below. | |||

Using both qualitative and quantitative methods has | |||

=The Three Models= | =The Three Models= | ||

Three models clearly emerge from analyzing assessment techniques used in organizations and research labs that account for the majority of them. The three models are the following: | Three models clearly emerge from analyzing assessment techniques used in organizations and research labs that account for the majority of them. The three models are the following: | ||

| Line 15: | Line 14: | ||

* '''Type models'''. Although the first typologies date back to ancient times, their statistical evaluation is more recent, and their use has grown significantly with the rise of coaching in the late 1980s. | * '''Type models'''. Although the first typologies date back to ancient times, their statistical evaluation is more recent, and their use has grown significantly with the rise of coaching in the late 1980s. | ||

The three models offer different understandings of how people | The three models offer different understandings of how people function from behavioral, emotional, and cognitive standpoints. Although each can be useful for addressing questions about people, they also have limitations and should be used wisely. Seeing people in context, or not, and with varying nuances, the three models ultimately carry a different vision of how people can be understood, how they possibly show up, grow, and perform. | ||

Seeing people in context, or not, and with varying nuances, the three models ultimately carry a different vision of how people | |||

==Measurement and Representation== | ==Measurement and Representation== | ||

| Line 27: | Line 24: | ||

==Adaptation== | ==Adaptation== | ||

Adaptation is an important aspect of what the three models deal with, because the object of their measure and representation, behavior, is in constant flux | Adaptation is an important aspect of what the three models deal with, because the object of their measure and representation, behavior, is in constant flux. Additionally, there is always an expectation, from the persons themselves, someone else, including management or HR, or from the organization at large, to behave in a certain way and adapt behavior accordingly. | ||

Adaptation is an important aspect of what the three models deal with, because the object of their measure and representation, behavior, is in constant flux. Additionally, there are always expectations to behave in a certain way and to adapt accordingly, from the person themselves, from someone else, including management, or from the organization at large. | |||

This important aspect of adaptation has repercussions for how one envisions a person’s growth, provides understanding and support, and ultimately, how the person takes on an assignment or a job and performs, including on an emotional level. | This important aspect of adaptation has repercussions for how one envisions a person’s growth, provides understanding and support, and ultimately, how the person takes on an assignment or a job and performs, including on an emotional level. Development happens differently for everyone, an aspect revealed with varying degrees of accuracy by the three models. This aspect is discussed below for each. | ||

Development happens differently for everyone, an aspect revealed with varying degrees of accuracy by the three models. This aspect is discussed below for each. | |||

=Factor Model= | =Factor Model= | ||

A factor model helps position a phenomenon along a continuum, represented by a line | A factor model helps position a phenomenon along a continuum, represented by a line extending from one end to the other in two opposite directions. | ||

A factor helps answer questions about how the phenomenon will develop along the continuum. For instance, with skills: how can this person develop or lose that skill? Or with localisation of a person on a map: how does one go from A to B or away from B. Or temperature: how can this temperature be increased or decreased? | A factor helps answer questions about how the phenomenon will develop along the continuum. For instance, with skills: how can this person develop or lose that skill? Or with localisation of a person on a map: how does one go from A to B or away from B. Or temperature: how can this temperature be increased or decreased? | ||

In the behavioral domain, the factor model provides answers to questions about how people behave and how they adapt their behavior. | |||

When adequately designed and represented, the factor model also applies at multiple levels, not only the individual level but also the job, team, company, and industry levels. This helps | |||

When adequately designed and represented, the factor model also applies at multiple levels, not only the individual level but also the job, team, company, and industry levels. This helps understand how individuals relate to their environment and how they adapt to it. | |||

==Representation== | ==Representation== | ||

[[File:Factor_San Francisco.png|right|250px]] | |||

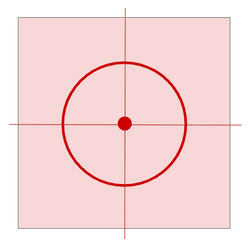

A factor model represents how an object or person can be situated on a two-dimensional map using latitude and longitude, as shown below with the red dot on Union Square in San Francisco. | A factor model represents how an object or person can be situated on a two-dimensional map using latitude and longitude, as shown below with the red dot on Union Square in San Francisco. | ||

A third factor, altitude, would help locate an object or person in space. Another factor, time, would add a fourth dimension to their location. | A third factor, altitude, would help locate an object or person in space. Another factor, time, would add a fourth dimension to their location. | ||

As with geolocation | As with geolocation, social behaviors may be located and represented by a limited number of factors. | ||

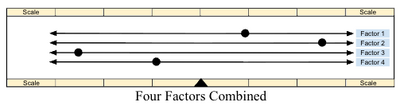

Using factor analysis, words and expressions depicting social behavior can be grouped into four clusters. Each cluster contains a latent hidden factor that can be represented by a continuum, like the longitude and latitude. A person’s factors can then be located on four continuums, with a standard deviation scale, as shown in the illustration below. | Using factor analysis, words and expressions depicting social behavior can be grouped into four clusters. Each cluster contains a latent hidden factor that can be represented by a continuum, like the longitude and latitude. A person’s factors can then be located on four continuums, with a standard deviation scale, as shown in the illustration below<ref>These paragraphs are a very condensed introduction of personality factors as they emerged over several decades of research, and have proven to be the most effective way to measure and represent social behavior.</ref>. Like latitude and longitude, which can locate an object on a map, the four factors add nuance to one another to describe a person’s social behavior. An individual’s specific behavior will be located by combining the four factors and analyzing them together. | ||

[[File:Four Factors Combined.png|center|400px]] | |||

Like latitude and longitude, which can locate an object on a map, the four factors add nuance to one another to describe a person’s social behavior. An individual’s specific behavior will be located by combining the four factors and analyzing them together. | |||

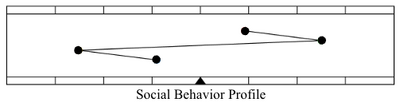

A unique profile can be created by connecting the four factors with lines, as shown below. This presentation of the four factors next to each other helps evidence their mutual influence | A unique profile can be created by connecting the four factors with lines, as shown below. This presentation of the four factors next to each other helps evidence their mutual influence and relative intensities. The visual characteristic of the profile, its shape, instantly combines the four factors, and, once learned, can gather the full meaning of the combinations. One can then use the profiles and continue learning from them and the people they represent. | ||

[[File:Social Behavior Profile.png|center|400px]] | |||

The visual characteristic of the profile, its shape, | |||

[[File:Social Behavior Profile.png|center| | |||

The relevance of the | The relevance of the profiles spans across various individual and organizational levels. As we do with the adaptive profiles at GRI, three profiles like the above combine, one representing a person’s behavior, the adaptation of the person to the environment, and how the two translate into the effective behaviors: the behavior most probably observed by others. | ||

The profiles can be used to represent the behaviors expected in a job, | The profiles can be used to represent the behaviors expected in a job, from a team, and from a company, or to describe behaviors at an industry and societal level. At all these levels, the words and expressions used to describe behaviors can be regrouped into the same clusters, as for people, and represented using the same four factors. | ||

When designed this way, the measures and representations from the assessment technique help analyze differences in social behavior across levels, to understand the efforts required for adaptation, and to envision how the adaptation will unfold. | When designed this way, the measures and representations from the assessment technique help analyze differences in social behavior across levels, to understand the efforts required for adaptation, and to envision how the adaptation will unfold. | ||

The above representation of the four factors together has been adopted, with minor variations, by several techniques since the 1950s. Some evolved with the representation of types and traits, keeping the factor model under the hood. Others, like GRI, both measure and use factor representations, bringing the power of the profiles and their precision closer to strategic decision-making. | The above representation of the four factors together has been adopted, with minor variations, by several techniques since the 1950s. Some evolved with the representation of types and traits, keeping the factor model under the hood. Others, like GRI, both measure and use factor representations, bringing the power of the profiles and their precision closer to strategic decision-making. | ||

==Measure= | ==Measure== | ||

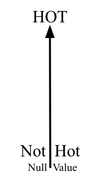

A factor is a measure on a continuum represented by a horizontal line and two poles, or more precisely vectors that run in opposite directions, which can locate various expressions of a phenomenon that are close, distant, at opposite ends to each other, and at different levels of intensity. The two extremities are opposite and extreme expressions of the phenomenon, with a neutral value between them, represented by a triangle. | A factor is a measure on a continuum represented by a horizontal line and two poles, or more precisely, vectors that run in opposite directions, which can locate various expressions of a phenomenon that are close, distant, at opposite ends to each other, and at different levels of intensity. The two extremities are opposite and extreme expressions of the phenomenon, with a neutral value between them, represented by a triangle. | ||

For instance, how hot or cold it is can be represented on a continuum, as illustrated below. The following adjectives: glacial, freezing, chilly, cool, lukewarm, tepid, torrid, steaming, roasting, boiling, etc, could locate the temperature on the continuum at different levels of intensity. | For instance, how hot or cold it is can be represented on a continuum, as illustrated below. The following adjectives: glacial, freezing, chilly, cool, lukewarm, tepid, torrid, steaming, roasting, boiling, etc, could locate the temperature on the continuum at different levels of intensity. | ||

[[File:Factor_temperature_scale_dot.png|center|400px]] | |||

When estimating room temperature, the neutral value may be close to the body temperature, while cold and hot may be moderately, very, or extremely distant from it. The red dot in the illustration indicates where a temperature measurement or best estimate may be. | |||

The scale used by an instrument may be similar to the one above, which duplicates the standard deviation scale we use at GRI for behaviors. Interval scales are also often used in personality assessments to measure behavioral intensity. | |||

As discussed below, most individual and group characteristics used in organizations, such as competencies, skills, abilities, and experience, have generally been represented by traits and types. However, social behaviors and emotions, like finding a location on a map, can be more precisely defined in terms of their factors. | |||

==Factors’ Measurement and Use== | ==Factors’ Measurement and Use== | ||

Factors have typically been measured using adjective lists, | Factors have typically been measured using adjective lists, whose analysis was at the origin of their discovery, and through open scenarios in which participants decide whether certain adjectives are part of their life experiences. Other techniques use questionnaires with forced-choice scenarios, a technique more common in trait assessments. | ||

In any case, these techniques enable the positioning of the four factors of an individual’s behavior along each of their continua. They have also allowed for measuring and representing an individual's behavior in their past, current, and immediate contexts, as well as how they engage within their environment. | In any case, these techniques enable the positioning of the four factors of an individual’s behavior along each of their continua. They have also allowed for measuring and representing an individual's behavior in their past, current, and immediate contexts, as well as how they engage within their environment. | ||

The use of the factor model includes | The use of the factor model includes trait and type models in recruitment, coaching, and team building (see below). It helps to take the analysis to jobs, refining the behaviors expected in them, and bringing greater rigor to understanding how a person will fit the job or how the job needs to adjust to them. The factor model offers greater sophistication and precision in representing behaviors than the trait and type models, enabling its use in organizational development by combining and analyzing multiple profiles across different levels of the individual, job, team, company, and industry. | ||

The factor model is the one among the three that offers the greatest capacity for developing people. As discussed below, our brain and senses generally first use the type and trait models. Those two easily preempt what might otherwise come from a factor model, until it’s learned and used. | The factor model is the one among the three that offers the greatest capacity for developing people. As discussed below, our brain and senses generally first use the type and trait models. Those two easily preempt what might otherwise come from a factor model, until it’s learned and used. | ||

On a 2-dimensional map, the factor model can | ==Adaptation Efforts== | ||

On a 2-dimensional map, the factor model can indicate where one is situated and where one needs to go, as well as the effort required to get from one location to the other. | |||

Similarly | Similarly, for behaviors, when going from A to B, the four factors together, within the profile, once measured, will inform what the behaviors are at the beginning and the end. Since the measures are behavioral, the measure wil also tell how this will happen. | ||

By comparison, the trait model can only indicate how close one is to the target location, but only imprecisely in its surroundings. And the type model only indicates whether one is within the region of the target location. Additionally, the two models cannot determine the effort required to go from A to B, nor how that journey will unfold. | |||

=Trait Model= | =Trait Model= | ||

| Line 105: | Line 98: | ||

==Representation== | ==Representation== | ||

[[File:Trait_San Francisco.png|right|250px]] | |||

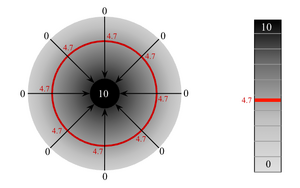

With most techniques, the further the measurement is from the targeted trait, the more different it may be, in many ways. This is shown in the map representation on the right, where the red rim indicates the distance to the targeted behavior. The trait’s measure may be anywhere on the rim. | |||

The intensity of a trait is typically represented on a decile scale. The maximum value of 10 indicates that the trait most probably and intensely applies to the person. The null value indicates that it doesn’t apply at all. The more the person is characterized by the trait, the more intense and the higher the measure is on the scale. As in the example on the right, 4.7 indicates the trait’s intensity on the decile scale. | The intensity of a trait is typically represented on a decile scale. The maximum value of 10 indicates that the trait most probably and intensely applies to the person. The null value indicates that it doesn’t apply at all. The more the person is characterized by the trait, the more intense and the higher the measure is on the scale. As in the example on the right, 4.7 indicates the trait’s intensity on the decile scale. | ||

The illustration to the left better shows that values away from the target are not at the opposite end of a continuum. They may be when the techniques actually measure factors and represent them as traits. | [[File:Factor_Circular and Bar.png|center|300px]] | ||

The illustration to the left better shows that values away from the target are not at the opposite end of a continuum. They may be when the techniques actually measure factors and represent them as traits. | |||

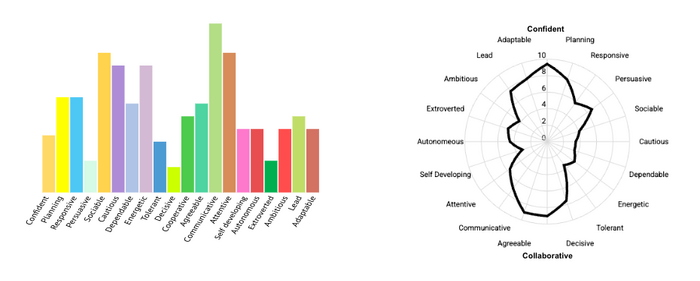

As shown below, traits measuring social behaviors often come in groups, represented as a bar (left) or a spider chart (right). The higher the bar, the more intense the trait is. The two charts give a different impression of the traits' proximity. Traits that are close and on the same side of the spider chart appear closer than those on the other side. This is also how systems using this representation organize the traits around a wheel. | As shown below, traits measuring social behaviors often come in groups, represented as a bar (left) or a spider chart (right). The higher the bar, the more intense the trait is. The two charts give a different impression of the traits' proximity. Traits that are close and on the same side of the spider chart appear closer than those on the other side. This is also how systems using this representation organize the traits around a wheel. | ||

[[File:Trait_basic_multiple spider.png|center|700px]] | |||

The charts give the impression that traits are distinct, but | The charts give the impression that traits are distinct, but treating them as factors reveals that they overlap and should be regrouped. The tendency has thus been to keep the number of traits to a minimum, close to four or five, as it emerged from factor model studies. | ||

Everyone develops a sense of what most traits mean. But a trait’s measure will be defined and analyzed differently by different people. Additionally, a concept can manifest in various ways, a phenomenon that cannot be captured by a single trait. | |||

Everyone develops a sense of what most traits mean. But a trait’s measure will be defined and analyzed differently by different people. Additionally, a concept can manifest in various ways, a phenomenon that cannot be captured by a single trait. | |||

==Measure== | ==Measure== | ||

A trait is measured on a continuum represented by a line with one pole, or a vector generally pointing upward, that | [[File:Trait_Hot not Hot.png|right|100px]] | ||

A trait is measured on a continuum represented by a line with one pole, or a vector generally pointing upward, that locates how close the measure is to the phenomenon of interest as conceptualized by a person or a system. | |||

The phenomenon of interest is at the top of the vector; its absence is at the bottom, with a null value, suggesting that the phenomenon may not occur at all or in a way that’s totally off focus. | The phenomenon of interest is at the top of the vector; its absence is at the bottom, with a null value, suggesting that the phenomenon may not occur at all or in a way that’s totally off focus. | ||

| Line 121: | Line 122: | ||

The trait model, with its continuum and bottom value, applies to many physical phenomena, such as mass, force, weight, length, speed, acceleration, mechanical power, and electrical power. It also applies to many concepts in social sciences, such as skills, competencies, abilities, experience, interests, and even cognitive abilities. | The trait model, with its continuum and bottom value, applies to many physical phenomena, such as mass, force, weight, length, speed, acceleration, mechanical power, and electrical power. It also applies to many concepts in social sciences, such as skills, competencies, abilities, experience, interests, and even cognitive abilities. | ||

==Traits’ Measurement and Use== | ==Traits’ Measurement and Use== | ||

Traits are used in recruitment, coaching, personal development, and to characterize what’s expected in jobs. They are also used for clinical assessment. For instance, the following are traits used in recruitment and coaching: Agreeable, Authoritative, Charismatic, Courageous, Creative, Exuberant, Flexible thinking, Honest, Leader, Loyal, Modest, Outgoing, Team | Traits are used in recruitment, coaching, personal development, and to characterize what’s expected in jobs. They are also used for clinical assessment. For instance, the following are traits used in recruitment and coaching: Agreeable, Authoritative, Charismatic, Courageous, Creative, Exuberant, Flexible thinking, Honest, Leader, Loyal, Modest, Outgoing, Team player, etc. | ||

When required by management, standardized surveys help recruiters save time by measuring traits expected for jobs and in candidates. Does one want to know whether a candidate can demonstrate leadership or creativity? The assessment technique will provide the answer. However, what’s really tested is the candidate's understanding of the concept being measured and | When required by management, standardized surveys help recruiters save time by measuring traits expected for jobs and in candidates. Does one want to know whether a candidate can demonstrate leadership or creativity? The assessment technique will provide the answer. However, what’s really tested is the candidate's understanding of the concept being measured and its impact on their Effective behavior<ref>This is the terminology of GRI’s adaptive profiles, which designates the behaviors effectively expressed by a person and most likely seen by observers. This profile is distinct from the natural and role behaviors measured with the Natural and Role profiles.</ref>. However, the trait model cannot speak to the effort required to sustain it. | ||

Clinicians are trained to understand and diagnose traits observed in clinical practice. Recruiters are also trained to interpret traits, but in work-related behaviors. Some techniques may measure both clinical behaviors and behaviors in the “normal” range, while others focus only on work behaviors and avoid clinical traits, enabling their use by non-clinicians. | Clinicians are trained to understand and diagnose traits observed in clinical practice. Recruiters are also trained to interpret traits, but in work-related behaviors. Some techniques may measure both clinical behaviors and behaviors in the “normal” range, while others focus only on work behaviors and avoid clinical traits, enabling their use by non-clinicians. | ||

| Line 132: | Line 133: | ||

==Adaptation Efforts== | ==Adaptation Efforts== | ||

In | The trait model can inform about how close one is to a targeted destination. In our example on the right, the destination is Union Square in San Francisco. But the departure may be anywhere, including the Pacific Ocean, Stockton, Sonoma, or Santa Cruz, which are within a 80 mile radius. The effort required to reach the destination may vary widely, but the model cannot inform about it. | ||

In social behaviors, as evidenced by a factor model with measures of adaptation and engagement, successful development will be reflected in how individuals perceive their adaptation<ref>We refer to how people perceive to adapt as the role behavior, represented in the adaptive profile with the Role profile.</ref> and how they ultimately show up<ref>We refer to how people effectively show up as the effective behavior, which combines how people naturally express themselves at flow (the Natural profile), with how they perceive to adapt (the Role profile). It is represented in the adaptive profile with the Effective profile.</ref>. | |||

In social behaviors, as evidenced by a factor model with measures of adaptation and engagement, successful development will be reflected in how individuals perceive their adaptation and how they ultimately show up. | |||

The development will probably not affect the person’s natural behavior, which is relatively stable, and if the adaptation is impactful and engaging over time. | The development will probably not affect the person’s natural behavior<ref>We refer to how people naturally and consistently show up at flow over time as the natural behavior. It is represented in the adaptive profile with the Natural profile.</ref>, which is relatively stable, and if the adaptation is impactful and engaging over time. | ||

The trait models, by design, cannot—on the basis of the | The trait models, by design, cannot—on the basis of the measure—evidence the efforts candidates or employees make to adapt their behavior to a job, from an emotional, cognitive, and social-behavioral standpoint, nor the amount and quality of support needed for the change to occur. | ||

==Factors versus Traits== | ==Factors versus Traits== | ||

| Line 151: | Line 151: | ||

A factor model shows that "Low in patience" is its own active state. A trait model simply labels someone as "Not patient," failing to capture the active nature of their behavior. It ignores the "low end" as a distinct quality, and loses qualitative data. | A factor model shows that "Low in patience" is its own active state. A trait model simply labels someone as "Not patient," failing to capture the active nature of their behavior. It ignores the "low end" as a distinct quality, and loses qualitative data. | ||

Modern researchers address the problem of the “low end” by using bipolar factor names (e.g., "Neuroticism vs. Emotional Stability") to ensure that both ends of the continuum have descriptive power. But they often fail to do so because the measures are represented in ways that cannot capture all the meaning along the continuum, which, by design, are antagonistic when they are on both sides, making them difficult to use. In the geolocation analogy, moving West isn't just "failing to move East." It is a specific direction with its own coordinates. Trait models "collapse" the scale, treating the zero point as a void rather than a distinct direction. | Modern researchers address the problem of the “low end” by using bipolar factor names (e.g., "Neuroticism vs. Emotional Stability") to ensure that both ends of the continuum have descriptive power. But they often fail to do so because the measures are represented in ways that cannot capture all the meaning along the continuum, which, by design, are antagonistic when they are on both sides, making them difficult to use. In the geolocation analogy, moving West isn't just "failing to move East." It is a specific direction with its own coordinates. Trait models "collapse" the scale, treating the zero point as a void rather than a distinct direction. | ||

=Type | |||

=Type Model= | |||

The type model is probably the most comprehensible and widely used, even without any sophisticated formal or statistics-based assessment technique. | The type model is probably the most comprehensible and widely used, even without any sophisticated formal or statistics-based assessment technique. | ||

Types help answer questions about whether a phenomenon exists or doesn’t, such as with hot temperature: Is it hot? Or with competences: is this person competent? Unlike factors and traits, which have continua, types have none. By doing so, the measurement of types disregards anything that doesn’t characterize and is distant from the phenomenon of interest. | Types help answer questions about whether a phenomenon exists or doesn’t, such as with hot temperature: Is it hot? Or with competences: is this person competent? Unlike factors and traits, which have continua, types have none. By doing so, the measurement of types disregards anything that doesn’t characterize and is distant from the phenomenon of interest. | ||

| Line 158: | Line 160: | ||

==Representation== | ==Representation== | ||

[[File:Type_San Francisco.png|right|250px]] | |||

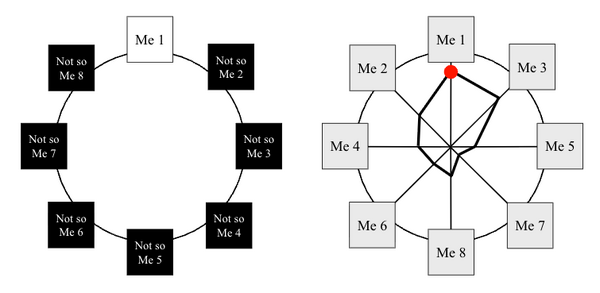

Types only provide a rough estimate of a characteristic, either it be competence or behavior. This is represented here with the red square on the map where you get an estimate of a person being somehow in the region of San Francisco, but without knowing the exact location. | Types only provide a rough estimate of a characteristic, either it be competence or behavior. This is represented here with the red square on the map where you get an estimate of a person being somehow in the region of San Francisco, but without knowing the exact location. | ||

| Line 171: | Line 174: | ||

The results are presented on the left as types, and on the right as traits. But we see type first and trait second, because types are easier to capture and use as on the left. It’s no effort for the brain, but also for the immediate deductions made from the types being measured. When combined, the same limitations apply to understanding traits: only one side of the continuum is revealed, and the other is ignored. | The results are presented on the left as types, and on the right as traits. But we see type first and trait second, because types are easier to capture and use as on the left. It’s no effort for the brain, but also for the immediate deductions made from the types being measured. When combined, the same limitations apply to understanding traits: only one side of the continuum is revealed, and the other is ignored. | ||

[[File:Type_circular representation.png|center|600px]] | |||

==Measure== | ==Measure== | ||

[[File:Type_temperature_simple.png|right|120px]] | |||

A type is a measure that is represented by a square that includes all the elements used to conceptualise the phenomenon of interest by a person or a technique. The phenomenon of focus is the center white square. Others that are not are outside in the outer black square. | A type is a measure that is represented by a square that includes all the elements used to conceptualise the phenomenon of interest by a person or a technique. The phenomenon of focus is the center white square. Others that are not are outside in the outer black square. | ||

| Line 178: | Line 183: | ||

The measure of a type may contain nuances, but this is not of concern for the representation and use of types. In comparison, the factor and trait models will reveal nuances that differ from those of a type assessment, especially from the factor model. | The measure of a type may contain nuances, but this is not of concern for the representation and use of types. In comparison, the factor and trait models will reveal nuances that differ from those of a type assessment, especially from the factor model. | ||

As for traits, types can be any individual characteristics one may think of. But unlike traits, types have no intensity. As with traits, factors will reveal how types are expressed and learned, with additional nuances that cannot be revealed by the type measurement. | As for traits, types can be any individual characteristics one may think of. But unlike traits, types have no intensity. As with traits, factors will reveal how types are expressed and learned, with additional nuances that cannot be revealed by the type measurement. | ||

==Types’ Measurement and Use== | ==Types’ Measurement and Use== | ||

| Line 202: | Line 207: | ||

Type models fail factor analysis because they assume a bimodal distribution of human behavior: One is either one of two categories of "Type A" or a "Type B," or is like in one room or another. With the geolocation analogy, a Type model divides the world into two halves: "The East" and "The West." Anyone at 1° West is grouped with someone at 179° West. A Factor model gives the exact longitude. It recognizes that 1° West is actually much more similar to 1° East than it is to 179° West. | Type models fail factor analysis because they assume a bimodal distribution of human behavior: One is either one of two categories of "Type A" or a "Type B," or is like in one room or another. With the geolocation analogy, a Type model divides the world into two halves: "The East" and "The West." Anyone at 1° West is grouped with someone at 179° West. A Factor model gives the exact longitude. It recognizes that 1° West is actually much more similar to 1° East than it is to 179° West. | ||

Soms techniques measure dimensions along continuums, but then reduce their representation to types. They do that, because it’s easier to think in term of types than continuums, but is not appropriate when requiring nuances as for instance in personal and organizational development. | Soms techniques measure dimensions along continuums, but then reduce their representation to types. They do that, because it’s easier to think in term of types than continuums, but is not appropriate when requiring nuances as for instance in personal and organizational development. | ||

Summary | |||

=Summary= | |||

The three types of techniques are summarized in the table below. | The three types of techniques are summarized in the table below. | ||

{|class="wikitable" style="margin: auto;" | |||

Type | ! !! Type !! Trait !! Factor | ||

Trait | |- | ||

Factor | | Representation<br/>Locating Social Behavior || [[File:Type_San Francisco.png|center|200px]]Behaviors are roughly measured. || [[File:Trait_San Francisco.png|center|200px]]The distance to a targeted behavior is measured. || [[File:Factor_San Francisco.png|center|200px]]Behaviors are precisely measured, including the distance to an objective. | ||

Representation | |- | ||

Locating Social Behavior | | Measurement || [[File:Type_Representation.png|center|100px]]Measure a rough location. Being in or out. || [[File:Trait_Representation.png|center|100px]]Measure approximate distance to the target. || [[File:Factor_Representation.png|center|200px]]Reveals precise location with nuances. | ||

|- | |||

Behaviors are roughly measured. | | Adapting Behavior, Development || A rough estimate of where the adaptation starts and ends, but not how it happens, nor the effort it takes to sustain the effort. || Understanding how distant the development is at the start and the end, but not how it happens, nor the effort it takes to sustain the effort. || Understanding where the development starts, where it ends, how it happens, and the effort it takes to sustain it. | ||

|- | |||

The distance to a targeted behavior is measured. | | Typical Usage || Coaching, Team Building, Counselling || Recruitment, vocational guidance, and other uses of types. || Management, leadership, organizational development, and other uses of types and traits. | ||

|- | |||

Behaviors are precisely measured, including the distance to an objective. | | Typically Measured || Up to a few dozen types. || Up to a few dozen traits. || Up to seven factors. | ||

Measurement | |- | ||

| Users || Coaches || Recruiters, clinicians, and coaches || Executives, managers, recruiters, clinicians and coaches | |||

Measure a rough location. Being in or out. | |- | ||

| Emergence || 1950s || 1910s ||2010s | |||

|} | |||

Reveals precise location with nuances. | |||

Adapting Behavior, Development | |||

A rough estimate of where the adaptation starts and ends, but not how it happens, nor the effort it takes to sustain the effort. | |||

Understanding how distant the development is at the start and the end, but not how it happens, nor the effort it takes to sustain the effort. | |||

Understanding where the development starts, where it ends, how it happens, and the effort it takes to sustain it. | |||

Typical | |||

Usage | |||

Coaching, Team Building, Counselling | |||

Recruitment, vocational guidance, and other uses of types. | |||

Management, leadership, organizational development, and other uses of types and traits. | |||

Typically Measured | |||

Up to a few dozen types. | |||

Up to a few dozen traits. | |||

Up to seven factors. | |||

Users | |||

Coaches | |||

Recruiters, clinicians, and coaches | |||

Executives, managers, recruiters, clinicians and coaches | |||

Emergence | |||

1950s | |||

1910s | |||

2010s | |||

The factor approach, with roots in research dating back to the era of Taylor, has progressively emerged since the 1950s. With social behavior, a major obstacle to their use has been the availability of trait and types models that are more immediate to understand and use but however have drawbacks that this article discusses. | The factor approach, with roots in research dating back to the era of Taylor, has progressively emerged since the 1950s. With social behavior, a major obstacle to their use has been the availability of trait and types models that are more immediate to understand and use but however have drawbacks that this article discusses. | ||

| Line 258: | Line 240: | ||

The real competing models to the three models, though, are executives’ and managers’ private techniques. Social behavior is the component of personality that’s the most universal, prevalent, intuitive, and subjective, and the one that takes the longest to educate. By bringing unparalleled precision and utility, including at a strategic level, the factor model provides the missing piece for social skills metrics to enhance decision making and communication. | The real competing models to the three models, though, are executives’ and managers’ private techniques. Social behavior is the component of personality that’s the most universal, prevalent, intuitive, and subjective, and the one that takes the longest to educate. By bringing unparalleled precision and utility, including at a strategic level, the factor model provides the missing piece for social skills metrics to enhance decision making and communication. | ||

=Notes= | |||

[[Category:Articles]] | |||

[[Category:Assessment]] | |||

Latest revision as of 06:30, 10 February 2026

Introduction

For decades, researchers and the personality assessment industry have studied and refined various methods for measuring personality in organizations. These methods are used for hiring, personal development, coaching, and more, including in clinical settings. We at GRI have reviewed these methods by analyzing their effects and benefits on individual and organizational performance, how they were developed, and by studying their users: traditional users like human resources managers, recruiters, coaches, and clinicians, as well as managers and executives.

In social matters, unlike in technology, as the history of assessment techniques shows, understanding their true potential develops slowly. This extended process may be due to a combination of factors: the abstract nature of the concepts being measured, the effort needed to learn these techniques, and the emotional attachment people develop toward them.

Assessment techniques can reveal their real capabilities through actual cases that genuinely matter. These cases usually come from organizations that care not only about performance in finance and production but also about how these outcomes are delivered from behavioral, cognitive, and emotional perspectives.

Using both qualitative and quantitative methods has helped us gain a detailed understanding of assessment techniques' capabilities and limitations: what they truly measure, how these measures are represented and used, and the questions they seek to answer. These topics are discussed below.

The Three Models

Three models clearly emerge from analyzing assessment techniques used in organizations and research labs that account for the majority of them. The three models are the following:

- Factor models. The factor approach emerged in the 1950s but did not gain widespread acceptance until research from the 1970s to the 1990s promoted a limited number of factors to explain behaviors.

- Trait models. These models were among the first to be used in psychiatry and clinical practice in the late 1800s. They were soon employed for large-scale recruitments and later for executive search.

- Type models. Although the first typologies date back to ancient times, their statistical evaluation is more recent, and their use has grown significantly with the rise of coaching in the late 1980s.

The three models offer different understandings of how people function from behavioral, emotional, and cognitive standpoints. Although each can be useful for addressing questions about people, they also have limitations and should be used wisely. Seeing people in context, or not, and with varying nuances, the three models ultimately carry a different vision of how people can be understood, how they possibly show up, grow, and perform.

Measurement and Representation

The three models, Factor, Trait, and Type, are used to both measure and represent behaviors, but the two aspects, measurement and representation, need to be considered separately, because a technique may use one model for measurement, but its representation may be based on one or a combination of the other two models.

For instance, some techniques measure factors and are thus factor-based. Whatever scales they use, which may vary greatly between the decile and standard deviation scales, they convert the measures of factors into traits or types and use the results as such, rather than using the factors themselves. The same happens with techniques that measure traits, which are represented as types.

The techniques end up being used as they are represented, but not for what they measure. Because of the combinations we see among the models, we differentiate them based on how they are both measured and represented.

Adaptation

Adaptation is an important aspect of what the three models deal with, because the object of their measure and representation, behavior, is in constant flux. Additionally, there is always an expectation, from the persons themselves, someone else, including management or HR, or from the organization at large, to behave in a certain way and adapt behavior accordingly.

Adaptation is an important aspect of what the three models deal with, because the object of their measure and representation, behavior, is in constant flux. Additionally, there are always expectations to behave in a certain way and to adapt accordingly, from the person themselves, from someone else, including management, or from the organization at large.

This important aspect of adaptation has repercussions for how one envisions a person’s growth, provides understanding and support, and ultimately, how the person takes on an assignment or a job and performs, including on an emotional level. Development happens differently for everyone, an aspect revealed with varying degrees of accuracy by the three models. This aspect is discussed below for each.

Factor Model

A factor model helps position a phenomenon along a continuum, represented by a line extending from one end to the other in two opposite directions.

A factor helps answer questions about how the phenomenon will develop along the continuum. For instance, with skills: how can this person develop or lose that skill? Or with localisation of a person on a map: how does one go from A to B or away from B. Or temperature: how can this temperature be increased or decreased?

In the behavioral domain, the factor model provides answers to questions about how people behave and how they adapt their behavior.

When adequately designed and represented, the factor model also applies at multiple levels, not only the individual level but also the job, team, company, and industry levels. This helps understand how individuals relate to their environment and how they adapt to it.

Representation

A factor model represents how an object or person can be situated on a two-dimensional map using latitude and longitude, as shown below with the red dot on Union Square in San Francisco.

A third factor, altitude, would help locate an object or person in space. Another factor, time, would add a fourth dimension to their location. As with geolocation, social behaviors may be located and represented by a limited number of factors.

Using factor analysis, words and expressions depicting social behavior can be grouped into four clusters. Each cluster contains a latent hidden factor that can be represented by a continuum, like the longitude and latitude. A person’s factors can then be located on four continuums, with a standard deviation scale, as shown in the illustration below[1]. Like latitude and longitude, which can locate an object on a map, the four factors add nuance to one another to describe a person’s social behavior. An individual’s specific behavior will be located by combining the four factors and analyzing them together.

A unique profile can be created by connecting the four factors with lines, as shown below. This presentation of the four factors next to each other helps evidence their mutual influence and relative intensities. The visual characteristic of the profile, its shape, instantly combines the four factors, and, once learned, can gather the full meaning of the combinations. One can then use the profiles and continue learning from them and the people they represent.

The relevance of the profiles spans across various individual and organizational levels. As we do with the adaptive profiles at GRI, three profiles like the above combine, one representing a person’s behavior, the adaptation of the person to the environment, and how the two translate into the effective behaviors: the behavior most probably observed by others.

The profiles can be used to represent the behaviors expected in a job, from a team, and from a company, or to describe behaviors at an industry and societal level. At all these levels, the words and expressions used to describe behaviors can be regrouped into the same clusters, as for people, and represented using the same four factors.

When designed this way, the measures and representations from the assessment technique help analyze differences in social behavior across levels, to understand the efforts required for adaptation, and to envision how the adaptation will unfold.

The above representation of the four factors together has been adopted, with minor variations, by several techniques since the 1950s. Some evolved with the representation of types and traits, keeping the factor model under the hood. Others, like GRI, both measure and use factor representations, bringing the power of the profiles and their precision closer to strategic decision-making.

Measure

A factor is a measure on a continuum represented by a horizontal line and two poles, or more precisely, vectors that run in opposite directions, which can locate various expressions of a phenomenon that are close, distant, at opposite ends to each other, and at different levels of intensity. The two extremities are opposite and extreme expressions of the phenomenon, with a neutral value between them, represented by a triangle.

For instance, how hot or cold it is can be represented on a continuum, as illustrated below. The following adjectives: glacial, freezing, chilly, cool, lukewarm, tepid, torrid, steaming, roasting, boiling, etc, could locate the temperature on the continuum at different levels of intensity.

When estimating room temperature, the neutral value may be close to the body temperature, while cold and hot may be moderately, very, or extremely distant from it. The red dot in the illustration indicates where a temperature measurement or best estimate may be.

The scale used by an instrument may be similar to the one above, which duplicates the standard deviation scale we use at GRI for behaviors. Interval scales are also often used in personality assessments to measure behavioral intensity.

As discussed below, most individual and group characteristics used in organizations, such as competencies, skills, abilities, and experience, have generally been represented by traits and types. However, social behaviors and emotions, like finding a location on a map, can be more precisely defined in terms of their factors.

Factors’ Measurement and Use

Factors have typically been measured using adjective lists, whose analysis was at the origin of their discovery, and through open scenarios in which participants decide whether certain adjectives are part of their life experiences. Other techniques use questionnaires with forced-choice scenarios, a technique more common in trait assessments.

In any case, these techniques enable the positioning of the four factors of an individual’s behavior along each of their continua. They have also allowed for measuring and representing an individual's behavior in their past, current, and immediate contexts, as well as how they engage within their environment.

The use of the factor model includes trait and type models in recruitment, coaching, and team building (see below). It helps to take the analysis to jobs, refining the behaviors expected in them, and bringing greater rigor to understanding how a person will fit the job or how the job needs to adjust to them. The factor model offers greater sophistication and precision in representing behaviors than the trait and type models, enabling its use in organizational development by combining and analyzing multiple profiles across different levels of the individual, job, team, company, and industry.

The factor model is the one among the three that offers the greatest capacity for developing people. As discussed below, our brain and senses generally first use the type and trait models. Those two easily preempt what might otherwise come from a factor model, until it’s learned and used.

Adaptation Efforts

On a 2-dimensional map, the factor model can indicate where one is situated and where one needs to go, as well as the effort required to get from one location to the other.

Similarly, for behaviors, when going from A to B, the four factors together, within the profile, once measured, will inform what the behaviors are at the beginning and the end. Since the measures are behavioral, the measure wil also tell how this will happen.

By comparison, the trait model can only indicate how close one is to the target location, but only imprecisely in its surroundings. And the type model only indicates whether one is within the region of the target location. Additionally, the two models cannot determine the effort required to go from A to B, nor how that journey will unfold.

Trait Model

The trait model is the most widely used in recruitment applications and clinical psychology. A trait can be any individual characteristic that you may think about, labeled with one word or a short expression.

Traits help answer questions about the attainment or proximity to a phenomenon or a concept, such as with hot temperature: How hot is it out there? Or with skills: How much skilled is this person? Or with creativity: How much creative is this person?

By doing so, trait measures focus on a phenomenon of interest, disregard the occurrences or expressions that are distant, and which, compared to the factor model, are eventually on the other side of the continuum.

Traits are easy to understand and use because they eventually correspond to how questions are naturally asked and answered. Traits are omnipresent. Except for clinical applications, traits usually require little explanation, can be learned fast, or may only require a reminder of their definition from the Internet.

Representation

With most techniques, the further the measurement is from the targeted trait, the more different it may be, in many ways. This is shown in the map representation on the right, where the red rim indicates the distance to the targeted behavior. The trait’s measure may be anywhere on the rim.

The intensity of a trait is typically represented on a decile scale. The maximum value of 10 indicates that the trait most probably and intensely applies to the person. The null value indicates that it doesn’t apply at all. The more the person is characterized by the trait, the more intense and the higher the measure is on the scale. As in the example on the right, 4.7 indicates the trait’s intensity on the decile scale.

The illustration to the left better shows that values away from the target are not at the opposite end of a continuum. They may be when the techniques actually measure factors and represent them as traits.

As shown below, traits measuring social behaviors often come in groups, represented as a bar (left) or a spider chart (right). The higher the bar, the more intense the trait is. The two charts give a different impression of the traits' proximity. Traits that are close and on the same side of the spider chart appear closer than those on the other side. This is also how systems using this representation organize the traits around a wheel.

The charts give the impression that traits are distinct, but treating them as factors reveals that they overlap and should be regrouped. The tendency has thus been to keep the number of traits to a minimum, close to four or five, as it emerged from factor model studies.

Everyone develops a sense of what most traits mean. But a trait’s measure will be defined and analyzed differently by different people. Additionally, a concept can manifest in various ways, a phenomenon that cannot be captured by a single trait.

Measure

A trait is measured on a continuum represented by a line with one pole, or a vector generally pointing upward, that locates how close the measure is to the phenomenon of interest as conceptualized by a person or a system.

The phenomenon of interest is at the top of the vector; its absence is at the bottom, with a null value, suggesting that the phenomenon may not occur at all or in a way that’s totally off focus.

In the example on the right, the focus is on “how hot is it?” which is represented at the top of the vector. The bottom values, which may indicate whether it’s cold, freezing, or just tepid, are irrelevant to answering the question.

The trait model, with its continuum and bottom value, applies to many physical phenomena, such as mass, force, weight, length, speed, acceleration, mechanical power, and electrical power. It also applies to many concepts in social sciences, such as skills, competencies, abilities, experience, interests, and even cognitive abilities.

Traits’ Measurement and Use

Traits are used in recruitment, coaching, personal development, and to characterize what’s expected in jobs. They are also used for clinical assessment. For instance, the following are traits used in recruitment and coaching: Agreeable, Authoritative, Charismatic, Courageous, Creative, Exuberant, Flexible thinking, Honest, Leader, Loyal, Modest, Outgoing, Team player, etc.

When required by management, standardized surveys help recruiters save time by measuring traits expected for jobs and in candidates. Does one want to know whether a candidate can demonstrate leadership or creativity? The assessment technique will provide the answer. However, what’s really tested is the candidate's understanding of the concept being measured and its impact on their Effective behavior[2]. However, the trait model cannot speak to the effort required to sustain it.

Clinicians are trained to understand and diagnose traits observed in clinical practice. Recruiters are also trained to interpret traits, but in work-related behaviors. Some techniques may measure both clinical behaviors and behaviors in the “normal” range, while others focus only on work behaviors and avoid clinical traits, enabling their use by non-clinicians.

Trait assessments are typically used before and after development to test a person’s learning of a new concept. Will the behavior change being learned be consistent over time and be reflected in how people act, decide, and emotionally respond? The difference in scores between the first and second measures will tell how much the person learned the concept. However, as with candidates, the technique cannot speak about the effort required to sustain the trait being developed.

Adaptation Efforts

The trait model can inform about how close one is to a targeted destination. In our example on the right, the destination is Union Square in San Francisco. But the departure may be anywhere, including the Pacific Ocean, Stockton, Sonoma, or Santa Cruz, which are within a 80 mile radius. The effort required to reach the destination may vary widely, but the model cannot inform about it.

In social behaviors, as evidenced by a factor model with measures of adaptation and engagement, successful development will be reflected in how individuals perceive their adaptation[3] and how they ultimately show up[4].

The development will probably not affect the person’s natural behavior[5], which is relatively stable, and if the adaptation is impactful and engaging over time.

The trait models, by design, cannot—on the basis of the measure—evidence the efforts candidates or employees make to adapt their behavior to a job, from an emotional, cognitive, and social-behavioral standpoint, nor the amount and quality of support needed for the change to occur.

Factors versus Traits

Factor models are often understood as Trait models because factor analysis solved the cumbersome problem of early trait theory by turning thousands of descriptors into a scientific system of measurement. It provided the mathematical evidence that personality includes stable, universal, enduring characteristics rather than temporary states or rigid categories.

Factors are factors; they are not traits. Factors have different attributes and potential than traits. As introduced above, factors are defined by two opposing poles or vectors.

Some techniques measure factors but represent them as traits, considering the entire axis as the trait. But the axis isn't just the high end; it should bring sensitivity to the underlying dimension, something the factor model does. Trait models create a linguistic "shorthand" that makes it seem as if only one end matters.

For example, if the factor is "Patient” vs. Impatient", being “low" in patience isn't an absence of something; it's the presence of a different, opposing behavior (impatience). As presented above, a factor can be viewed as longitude (East vs. West), while a trait is unipolar and can be viewed as a "fuel tank." You either have a lot of "patience" or very little. In the trait view, "Impatience" isn't a destination; it's just an empty tank of Patience.

A factor model shows that "Low in patience" is its own active state. A trait model simply labels someone as "Not patient," failing to capture the active nature of their behavior. It ignores the "low end" as a distinct quality, and loses qualitative data.

Modern researchers address the problem of the “low end” by using bipolar factor names (e.g., "Neuroticism vs. Emotional Stability") to ensure that both ends of the continuum have descriptive power. But they often fail to do so because the measures are represented in ways that cannot capture all the meaning along the continuum, which, by design, are antagonistic when they are on both sides, making them difficult to use. In the geolocation analogy, moving West isn't just "failing to move East." It is a specific direction with its own coordinates. Trait models "collapse" the scale, treating the zero point as a void rather than a distinct direction.

Type Model

The type model is probably the most comprehensible and widely used, even without any sophisticated formal or statistics-based assessment technique. Types help answer questions about whether a phenomenon exists or doesn’t, such as with hot temperature: Is it hot? Or with competences: is this person competent? Unlike factors and traits, which have continua, types have none. By doing so, the measurement of types disregards anything that doesn’t characterize and is distant from the phenomenon of interest. Like traits, types are easy to understand, probably easier, because how questions are asked and answered come even more naturally and spontaneously with types. Types are easy to learn and use, though they cannot convey nuances as the factor and trait models can.

Representation

Types only provide a rough estimate of a characteristic, either it be competence or behavior. This is represented here with the red square on the map where you get an estimate of a person being somehow in the region of San Francisco, but without knowing the exact location.

If you like to go from A to B on that red map you can’t possibly know, because you donùt have the information. Or if you come from another location, you may only endup somehow in the region, including the Pacific Ocean.

By design, types cannot capture important nuances. This becomes evident when comparing results of types with those of trait and factor models: those two reveal characteristics that types can’t. If you only use types, you can’t reqlly know until you try, and as in our example, may end up in the water. The measures of types suggest that those rough characteristics get attached to people and are likely to persist over time. But that’s far from reality and what what everyone can experience on their own. As for competences, behaviors develop and grow. People adapt, and eventually change, or not. Some béhaviors may be engaging, others may be lessm differently so for everyone.

Having a picture of whether someone is competent and exhibits a particular behavior type today cannot capture the picture of how they will be competent and show up tomorrow and beyond. The type being measured is only a far-from-perfect indicator of competence and behavior at the time of assessment. The first impression of being of a type subsists and further misguides consistent development. Types may inform about a person’s modus operandi, but inconsistently, due to their limitations.

Some systems combine the type and trait models to inform about a person's type’s representativeness and intensity, as traits do, as shown in the example below on the right.

The results are presented on the left as types, and on the right as traits. But we see type first and trait second, because types are easier to capture and use as on the left. It’s no effort for the brain, but also for the immediate deductions made from the types being measured. When combined, the same limitations apply to understanding traits: only one side of the continuum is revealed, and the other is ignored.

Measure

A type is a measure that is represented by a square that includes all the elements used to conceptualise the phenomenon of interest by a person or a technique. The phenomenon of focus is the center white square. Others that are not are outside in the outer black square.

In the example on the right, the focus is on answering the question “Is it hot?” The characteristics that qualify as hot are in the square. Others are out. The considerations differ from those of the factor and trait models, which address the development or proximity of the phenomenon. The measure of a type may contain nuances, but this is not of concern for the representation and use of types. In comparison, the factor and trait models will reveal nuances that differ from those of a type assessment, especially from the factor model.

As for traits, types can be any individual characteristics one may think of. But unlike traits, types have no intensity. As with traits, factors will reveal how types are expressed and learned, with additional nuances that cannot be revealed by the type measurement.

Types’ Measurement and Use

Types, like traits, are generally measured with forced-choise scenarios surveys.

Types have been used in personal development and coaching to form a first impression of a person: gauge who they are, and establish a connection. Factor and trait models are used this way, too, each revealing additional precisions and capabilities. When taken at the organizational level, types are used to regroup people into categories, typically a 2x2 matrix, and have a first understanding of a group’s dynamique and of people who may fit into them.

But they lack the nuances needed to, for instance, better characterize what is expected of a person in a job or what happens at a team level. The limitations and imprecision of type measurements prevent making any meaningful deductions that’s valid at individual and job levels. Types are used for team building, which, through their far-from-perfect descriptions, enables people to think about behavioral differences. At a minimum, a team-building exercise helps challenge assumptions that focus exclusively on cognitive abilities or other characteristics that are more evident but less relevant to understanding social interactions.

Types tap into people’s curiosity, are easy to start a discussion with, and benefit from what we’ve called art GRI medium effects: the capacity of a technique to help engage people in discussion. Soem people may not otherwise share without the type used as a medium, which can be a first great accomplishment.

Adaptation Efforts

With social behaviors, types provide an approximate estimate of individual characteristics, but without more nuances, fail to inform what it takes to adapt the behaviors to a job demand, from an emotional, cognitive, and social-behavioral standpoint, nor the amount and quality of support needed for the change to occur.

In the map analogy, the location of someone’s behavior is broad. When going somewhere like San Francisco, the departure may be anywhere within the red square on the map. As for the trait model, the departure may be in the Pacific Ocean, in Sonoma, or Santa Clara Counties, all of which are 40 to 80 miles distant. Or it may be in San Francisco and even in Union Square, the targeted destination in our example: there is no possible indication of the distance to the target, as with the trait and factor models. You may well already be at the destination, but the model cannot tell and only provides a rough sense that you are around.

Factors versus Types

Unlike Types models, which roughly describe someone’s characteristics in a square, Factor models provide their coordinates on the human spectrum. When applying Factor models to types, people’s behavior don't cluster into "types." Instead, they fall on a continuum. Applying a standard deviation scale, most, around two thirds, fall in the middle of the continuum. The "type" is an arbitrary cut-off on the Factor scale, with a divide between the two halves that looks like an empty space rather than being filled with most people.

Type models fail factor analysis because they assume a bimodal distribution of human behavior: One is either one of two categories of "Type A" or a "Type B," or is like in one room or another. With the geolocation analogy, a Type model divides the world into two halves: "The East" and "The West." Anyone at 1° West is grouped with someone at 179° West. A Factor model gives the exact longitude. It recognizes that 1° West is actually much more similar to 1° East than it is to 179° West.

Soms techniques measure dimensions along continuums, but then reduce their representation to types. They do that, because it’s easier to think in term of types than continuums, but is not appropriate when requiring nuances as for instance in personal and organizational development.

Summary

The three types of techniques are summarized in the table below.

| Type | Trait | Factor | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Representation Locating Social Behavior |

Behaviors are roughly measured. | The distance to a targeted behavior is measured. | Behaviors are precisely measured, including the distance to an objective. |

| Measurement | Measure a rough location. Being in or out. | Measure approximate distance to the target. | Reveals precise location with nuances. |

| Adapting Behavior, Development | A rough estimate of where the adaptation starts and ends, but not how it happens, nor the effort it takes to sustain the effort. | Understanding how distant the development is at the start and the end, but not how it happens, nor the effort it takes to sustain the effort. | Understanding where the development starts, where it ends, how it happens, and the effort it takes to sustain it. |

| Typical Usage | Coaching, Team Building, Counselling | Recruitment, vocational guidance, and other uses of types. | Management, leadership, organizational development, and other uses of types and traits. |

| Typically Measured | Up to a few dozen types. | Up to a few dozen traits. | Up to seven factors. |

| Users | Coaches | Recruiters, clinicians, and coaches | Executives, managers, recruiters, clinicians and coaches |

| Emergence | 1950s | 1910s | 2010s |

The factor approach, with roots in research dating back to the era of Taylor, has progressively emerged since the 1950s. With social behavior, a major obstacle to their use has been the availability of trait and types models that are more immediate to understand and use but however have drawbacks that this article discusses.

The factor model uniquely serves management and organizational development by offering a nuanced snapshot of individual behaviors, including most preferred and predictable behaviors, the efforts required to adapt, and engage in the job.

It also provides a refined understanding of the behaviors expected at the job, team, and organizational levels, which can be represented the same way as with people, helping to see and fill the gaps between the levels.

With critical nuances and representations that other models cannot handle, the factor model can better serve executives and managers in developing their social skills, coaches and recruiters to work more effectively with them, and researchers investigating and testing new models. In a similar way, type models have helped coaches, and trait models clinicians and recruiters for decades to serve management and organizational needs, but with limited capabilities.

The real competing models to the three models, though, are executives’ and managers’ private techniques. Social behavior is the component of personality that’s the most universal, prevalent, intuitive, and subjective, and the one that takes the longest to educate. By bringing unparalleled precision and utility, including at a strategic level, the factor model provides the missing piece for social skills metrics to enhance decision making and communication.

Notes

- ↑ These paragraphs are a very condensed introduction of personality factors as they emerged over several decades of research, and have proven to be the most effective way to measure and represent social behavior.

- ↑ This is the terminology of GRI’s adaptive profiles, which designates the behaviors effectively expressed by a person and most likely seen by observers. This profile is distinct from the natural and role behaviors measured with the Natural and Role profiles.

- ↑ We refer to how people perceive to adapt as the role behavior, represented in the adaptive profile with the Role profile.

- ↑ We refer to how people effectively show up as the effective behavior, which combines how people naturally express themselves at flow (the Natural profile), with how they perceive to adapt (the Role profile). It is represented in the adaptive profile with the Effective profile.

- ↑ We refer to how people naturally and consistently show up at flow over time as the natural behavior. It is represented in the adaptive profile with the Natural profile.