Performance by Values: Difference between revisions

| (34 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[File:Performance_Values.png|right| | [[File:Performance_Values.png|right|450px]] | ||

=Introduction= | |||

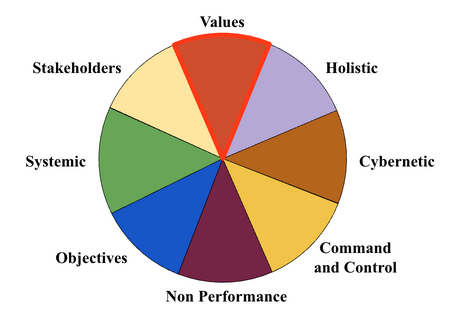

Performance by | Performance models based on values extend stakeholder models by explaining organizational performance in terms of individual values and preferences. These models have become increasingly important in our research at GRI for analyzing performance<ref>[[Performance_Models|See here an overview of performance models.]]</ref>, as they more closely address social behavior than other approaches. | ||

At an individual level, values are typically defined as the fundamental principles, beliefs, and ideals | At an individual level, values are typically defined as the fundamental principles, beliefs, and ideals a person considers essential in their life. Values are expressed, observed, and developed through social behavior. | ||

At the organizational level, values are the core beliefs and principles an organization regards as essential for guiding its actions, decisions, and social behavior. In both cases, the concept of values encompasses broad aspects of social behavior that, unlike any other abstract concepts, can be observed, measured, and compared at different levels. | |||

=Generalities= | =Generalities= | ||

Unlike other stakeholder approaches that focus on one specific variable and method with narrow applications, the approach of performance by values is broad, practical, and includes behaviors that can easily and objectively be described, measured, and shared. The framework is applicable to a variety of situations, stakeholders, and industries in different countries and cultures. | |||

Behavioral values can be regrouped along two dimensions and represented in a 2x2 grid, which then provides a framework for analyzing how an organization and its members perform. Along those lines, the competing value model is the most thought-out model for the approach of performance based on values. It provides the foundational logic for its establishment and deployment, something that the GRI model greatly learned from. | |||

However, the subjectivity of these two concepts of values and preferences is a significant obstacle. This is first reviewed below. Understanding that preferences and values typically compete opens up new ways to understand, manage, and enhance performance. | However, the subjectivity of these two concepts of values and preferences is a significant obstacle. This is first reviewed below. Understanding that preferences and values typically compete opens up new ways to understand, manage, and enhance performance. | ||

When discussing values, preferences, and behaviors, GRI’s terminology is included in this article within brackets for those already | When discussing values, preferences, and behaviors, GRI’s terminology is included in this article within brackets for those already familiar with it, to help them understand this article. It will display, such as [High 1] or [High 4, with 4 higher than 3]. For others, please ignore. | ||

=Performance and Subjectivity= | =Performance and Subjectivity= | ||

Unless being objectified, performance as a concept is primarily subjective, a challenge faced not only when being analyzed through individual preferences and values, but also through the objectives being set for the organization and its units, or through the stakeholders or constituencies of the organizations. | Unless being objectified, performance as a concept is primarily subjective, a challenge faced not only when being analyzed through individual preferences and values, but also through the objectives being set for the organization and its units, or through the stakeholders or constituencies of the organizations<ref>Van de Ven, A. H., Ferry, D. (1980). Measuring and Assessing organizations. New York: Wiley.<br/>Bluedorn, A. C. (1980). Cutting the Gordian knot: A critique of the effectiveness tradition in organizational research. Sociology and Social Research, 64, 477-496<br/>Connoly, T., Colon E. M., Deutch, S. J. (1980). Organizational effectiveness: a multiple constituency approach. Academy of Management review, 5, 211-218.</ref>. | ||

Studies conducted on the preferences of individuals and stakeholders are symptomatic of the problems posed by subjectivity when assessing performance. A major problem is that most people cannot identify their own preferences. What they usually report corresponds to their implicit theories or past behaviors that are plausible, but not to the preferences held by the individuals being assessed. | Studies conducted on the preferences of individuals and stakeholders are symptomatic of the problems posed by subjectivity when assessing performance. A major problem is that most people cannot identify their own preferences. What they usually report corresponds to their implicit theories or past behaviors that are plausible, but not to the preferences held by the individuals being assessed<ref>Nisbet, R. E., Wilson, T. (1977). Telling more than we can know: Verbal reports on mental processes; Psychological Review, 134, 231-259.</ref>. Research has evidenced a weak correlation between the knowledge of implicit preferences and motivational factors on one hand, and the preferences or actions that were selected as important from a behavioral standpoint on the other hand<ref>Slovic, P., Lichtenstein, S. (1971). Comparison of Bayesian and regression approaches to the study of information processing in judgement. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 6, 649-744.</ref>. | ||

While trying to differentiate the 'theories in action' from the 'theories in use', another study found that the theories in people's minds do not correspond with the theories they put into action<ref>Argyris, C, Schon, D. (1978). Organizational learning: A theory of action perspective. Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley.</ref>. When lists of criteria are presented to individuals, this other study found it difficult to select the criteria that people consider important or those that are not<ref>Gross, E., Grambsch, P. V. (1968). University goals and academic power. Washington, D. C.: American Council on Education. | |||

</ref>. Different techniques have been devised to solve the problem of identifying performance criteria, such as: | |||

While trying to differentiate the 'theories in action' from the 'theories in use', another study found that the theories in people's minds do not correspond with the theories they put into action. | |||

When lists of criteria are presented to individuals, this other study found it difficult to select the criteria that people consider important or those that are not. Different techniques have been devised to solve the problem of identifying performance criteria, such as: | |||

<ul> | <ul> | ||

<li>Capturing policies</li> | <li>Capturing policies<ref>Hammond, K. R., McClelland, G. H., Mumpower, J. (1980) Human judgement and decision making: Theories, methods, and procedures. New York : Praeger.</ref></li> | ||

<li>Nominal groups or the Delphi technique</li> | <li>Nominal groups or the Delphi technique<ref>Delbecq, A. L, Van de Ven, A. H., Gustafson, D. H. (1975). Group techniques for program planning. Glenview, Ill.: Scott Foresman.</ref></li> | ||

<li>Multi-attribute utilities</li> | <li>Multi-attribute utilities<ref>Huber, G. P. (1974). Methods for quantifying subjective probabilities and multi-attribute utilities. Decision Sciences, 5, 3-31.</ref></li> | ||

</ul> | </ul> | ||

However, each of these techniques only serves to weigh a preference order. They rely on individuals’ ability to specify preferences with precision. They cannot ensure that the performance or effectiveness criteria identified a priori by individuals or implicitly held by them are the most important. | However, each of these techniques only serves to weigh a preference order. They rely on individuals’ ability to specify preferences with precision. They cannot ensure that the performance or effectiveness criteria identified a priori by individuals or implicitly held by them are the most important. Not only do people have difficulty identifying performance criteria, but their preference for a particular criterion can change over time<ref>McDonald, J. (1975). The game of business. Garden City, N.Y.: Anchor Press.<br/>Quinn, R. E., Cameron, K. S. (1982). Life cycles and shifting criteria of effectiveness: Some preliminary evidence. Management Science, 27.<br/>Miles, R. H., Cameron, K. S. (1982). Coffin nails and corporate strategies. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.</ref>. The relationships between the criteria at two different times are unclear; in fact, performance in the past may not be a good predictor of effectiveness in the present and the future. | ||

Not only do people have difficulty identifying performance criteria, but their preference for a particular criterion can change over time. The relationships between the criteria at two different times are unclear; in fact, performance in the past may not be a good predictor of effectiveness in the present and the future. | |||

=The Means for Reaching Objectives= | =The Means for Reaching Objectives= | ||

| Line 39: | Line 35: | ||

Failure to achieve objectives then raises the question of the means that have not made it possible to achieve them. A variation of means calls into question the relevance of the objectives. | Failure to achieve objectives then raises the question of the means that have not made it possible to achieve them. A variation of means calls into question the relevance of the objectives. | ||

The dilemma between means and ends has been analyzed as a conflict between short and long-term perspectives. It opens up for discussions and arbitration to a point that may be described as optimal. | The dilemma between means and ends has been analyzed as a conflict between short and long-term perspectives<ref>Lawrence, P. R., Lorsch, J. W. (1967). Organization and Environment. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.</ref>. It opens up for discussions and arbitration to a point that may be described as optimal<ref>Katz D., Kahn, R.L. (1978). The social psychology of organization. New York: Willey. Originally published in 1966.</ref>. | ||

At the organizational level, the notions of objectives and means are tightly linked. They are also linked to individuals' preferences or values. Both personally and organizationally, practical concerns arise to consider these two aspects together and as interdependent. | At the organizational level, the notions of objectives and means are tightly linked. They are also linked to individuals' preferences or values. Both personally and organizationally, practical concerns arise to consider these two aspects together and as interdependent. | ||

| Line 45: | Line 42: | ||

Several performance criteria can be seen as in competition or paradoxical rather than being compatible or congruent. To be effective and to exist, an organization must possess attributes that are, at the same time, all present and operate in concert, while being contradictory or even exclusive. | Several performance criteria can be seen as in competition or paradoxical rather than being compatible or congruent. To be effective and to exist, an organization must possess attributes that are, at the same time, all present and operate in concert, while being contradictory or even exclusive. | ||

For example, the following attributes are found simultaneously in organizations: | For example, the following attributes are found simultaneously in organizations<ref>Cameron, K. S. (1986). Effectiveness as Paradox: Consensus and Conflict in Conceptions of Organizational Effectiveness. Vol. 32, No. 5, pp 539-553.</ref>: | ||

<ol> | <ol> | ||

<li>A weak coupling of attributes that encourages initiative, innovation, and functional autonomy [Low 3, high 1, low 4], at the same time as a strong coupling of attributes that encourages rapid execution, the implementation of innovation, and functional reciprocity [low 3, low 1, high 4].</li> | <li>A weak coupling of attributes that encourages initiative, innovation, and functional autonomy [Low 3, high 1, low 4], at the same time as a strong coupling of attributes that encourages rapid execution, the implementation of innovation, and functional reciprocity [low 3, low 1, high 4].</li> | ||

<li>The high specialization of roles, which reinforces expertise and efficiency [low 3, high 4], as well as the generalist roles, which reinforce flexibility and interdependence [1 higher than 4, Low 1].</li> | <li>The high specialization of roles, which reinforces expertise and efficiency [low 3, high 4], as well as the generalist roles, which reinforce flexibility and interdependence [1 higher than 4, Low 1].</li> | ||

<li>The continuity of leadership, which allows stability, long-term planning, and institutional memory [high 4, high 3, low 1] at the same time as the recruitment of new leaders, which allows for increased innovation and adaptability [high 1, low 4].</li> | <li>The continuity of leadership, which allows stability, long-term planning, and institutional memory [high 4, high 3, low 1], at the same time as the recruitment of new leaders, which allows for increased innovation and adaptability [high 1, low 4].</li> | ||

<li>Processes of amplifying deviant phenomena that encourage productive conflicts and energizing productive oppositions for the organization [high 1], as well as processes of reducing deviant phenomena that encourage the need for harmony and consensus to generate trust and circulate information [low 1, high 2].</li> | <li>Processes of amplifying deviant phenomena that encourage productive conflicts and energizing productive oppositions for the organization [high 1], as well as processes of reducing deviant phenomena that encourage the need for harmony and consensus to generate trust and circulate information [low 1, high 2].</li> | ||

<li>Increased research to make decisions that allow access to more information, increased presence, varied sources of stimulation [low 3, high 2], as well as the creation of inhibitors to stop the information overload that reduces the amount of information for decision-makers and leads to convergence in decision-making [low 2].</li> | <li>Increased research to make decisions that allow access to more information, increased presence, varied sources of stimulation [low 3, high 2], as well as the creation of inhibitors to stop the information overload that reduces the amount of information for decision-makers and leads to convergence in decision-making [low 2].</li> | ||

<li>The disengagement from past strategies which allowed for the emergence of new perspectives and innovation, and focusses the definition of new problems [high 1, Low 4], to variations of old problems, as well as the reintegration and reinforcement of the basic aspects that consolidate the adhesion to the specific corporate identity, mission, and strategies from the past [high 2, high 4, low 1].</li> | <li>The disengagement from past strategies which allowed for the emergence of new perspectives and innovation, and focusses the definition of new problems [high 1, Low 4], to variations of old problems, as well as the reintegration and reinforcement of the basic aspects that consolidate the adhesion to the specific corporate identity, mission, and strategies from the past [high 2, high 4, low 1].</li> | ||

</ol> | </ol> | ||

These criteria are those that overlap several studies aimed at assessing an organization’s performance. The result is a ranking of performance values along three dimensions: | =The Competing Value Models= | ||

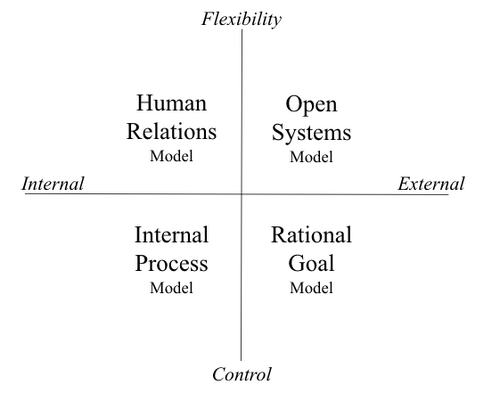

In response to the problems posed by the competition and paradox between performance criteria, the performance model based on competing values offers a synthesis of the possible links between an organization's preferences/values and those of its stakeholders<ref>Quinn, R. E., Rohrbaugh J. (1983). A Spatial Model of Effectiveness Criteria: towards a Competing Values Approach to Organizational Analysis. Management Science. Vol. 29, No. 3, pp. 363-377. | |||

</ref>. | |||

The starting point of the competing values models is the arrangement of about thirty criteria evaluated by a group of experts using multivariate techniques. These criteria are those that overlap several studies aimed at assessing an organization’s performance. The result is a ranking of performance values along three dimensions: | |||

<ul> | <ul> | ||

<li>Structure: flexible versus control</li> | <li>Structure: flexible versus control</li> | ||

| Line 68: | Line 67: | ||

The "Focus" dimension contrasts internal and external approaches within stakeholder models. These two competing values are fundamental to an organization’s existence. With an External focus, the organization functions as a logically structured tool aimed at acquiring resources and achieving goals. The focus is on maintaining the organization’s competitiveness in a dynamic environment [low 1, high 2, high 3, low 4]. Conversely, with an Internal focus, the organization is seen as a socio-technical system. Its members have unique feelings, interests, preferences, and values that must be considered within their work environment [high 1, low 2, low 3, high 4]. While the internal focus addresses micro-level aspects, the external focus emphasizes macro-level aspects. | The "Focus" dimension contrasts internal and external approaches within stakeholder models. These two competing values are fundamental to an organization’s existence. With an External focus, the organization functions as a logically structured tool aimed at acquiring resources and achieving goals. The focus is on maintaining the organization’s competitiveness in a dynamic environment [low 1, high 2, high 3, low 4]. Conversely, with an Internal focus, the organization is seen as a socio-technical system. Its members have unique feelings, interests, preferences, and values that must be considered within their work environment [high 1, low 2, low 3, high 4]. While the internal focus addresses micro-level aspects, the external focus emphasizes macro-level aspects. | ||

[[File:Performance_Competing_Values.png|right| | [[File:Performance_Competing_Values.png|right|500px]] | ||

As discussed above, the dimension that opposes means to ends refers to the approaches of objectives and systems. Organizations strive to achieve goals through the management of both animated (people) and inanimate (things) means that help them reach their objectives, especially those means that become functionally autonomous, i.e., that function as organizational objectives. This third component of means-ends was later integrated into the other two dimensions: Flexibility/Control and Internal/External. These last two dimensions sufficiently account for the four models of organizational performance represented on the right. | As discussed above, the dimension that opposes means to ends refers to the approaches of objectives and systems. Organizations strive to achieve goals through the management of both animated (people) and inanimate (things) means that help them reach their objectives, especially those means that become functionally autonomous, i.e., that function as organizational objectives<ref>Georgopoulos, B. S., Tannenbaum, A. S. (1957). A study of Organizational Effectiveness. American Sociological Review, 22, 534-540.</ref>. This third component of means-ends was later integrated into the other two dimensions: Flexibility/Control and Internal/External<ref>Quinn, R. E. (1988) Beyond rational management. Mastering the Paradoxes and Competing Demands of High Performance. San Francisco, California, Jossey-Bass.</ref>. These last two dimensions sufficiently account for the four models of organizational performance represented on the right. | ||

<ol> | <ol> | ||

| Line 82: | Line 81: | ||

By facilitating an analysis of both the objectives to be achieved and the means to be pursued, the values model can be considered the most comprehensive analytical framework for analyzing and assisting in developing performance. | By facilitating an analysis of both the objectives to be achieved and the means to be pursued, the values model can be considered the most comprehensive analytical framework for analyzing and assisting in developing performance. | ||

The framework enables articulating practical actions in organizations by considering both the means and the objectives, allowing intervention methods to analyze potential shortcomings and optimize the organization's functioning. | The framework enables articulating practical actions in organizations by considering both the means and the objectives, allowing intervention methods to analyze potential shortcomings and optimize the organization's functioning<ref>Quinn, R. E. (1988) Beyond rational management. Mastering the Paradoxes and Competing Demands of High Performance. San Francisco, California, Jossey Bass.</ref>. | ||

=Extending Grid Analysis to Other Models= | =Extending Grid Analysis to Other Models= | ||

The competing value model can be compared to other models that operate at different levels and for various applications, but nevertheless use similar dimensions, enabling the comparison of human dynamics | The competing value model can be compared to other models that operate at different levels and for various applications, but nevertheless use similar dimensions, enabling the comparison of human dynamics and how stakeholders connect with the organization at these different levels. | ||

This includes the AGIL framework elaborated at a societal level by Parsons and Shils , where the two axes of analysis are closely aligned. The adaptive functions (A) parallel the open systems model, the goal attainment functions (G) align with the rational goals model, the integration functions (I) compare with the internal processes model, and the latency and maintenance functions (L) relate to the human relations model. | This includes the AGIL framework elaborated at a societal level by Parsons and Shils<ref>Parsons, T., Shils, E. A. (2001). Toward a general theory of action.: theoretical foundations for the social science. New York: The Free Press. First published in 1951.</ref>, where the two axes of analysis are closely aligned. The adaptive functions (A) parallel the open systems model, the goal attainment functions (G) align with the rational goals model, the integration functions (I) compare with the internal processes model, and the latency and maintenance functions (L) relate to the human relations model. | ||

Analyzing organizations as dynamic systems, Katz and Kahn's open systems model presents a classification based on functions along two axes: internal vs. external, and Economical/instrumental vs. political/integrative. The adaptive category parallels the open systems model, the productive category aligns with the rational goals model, the maintenance category compares with the internal processes model, and the integrative category relates to the human relations model. | Analyzing organizations as dynamic systems, Katz and Kahn's open systems model<ref>Katz D., Kahn, R.L. (1978). The social psychology of organization. New York: Wiley & Sons. Originally published in 1966.</ref> presents a classification based on functions along two axes: internal vs. external, and Economical/instrumental vs. political/integrative. The adaptive category parallels the open systems model, the productive category aligns with the rational goals model, the maintenance category compares with the internal processes model, and the integrative category relates to the human relations model. | ||

Other models have used a similar 2x2 grid representation with two comparable axes, but different topics than the above, including the following: | Other models have used a similar 2x2 grid representation with two comparable axes, but for covering different topics than the above, including the following: | ||

<ul> | <ul> | ||

<li>Situational leadership (Hersey, Blanchard & Johnson)<ref></ref></li> | <li>Situational leadership (Hersey, Blanchard & Johnson)<ref>Hersey, P., Blanchard, K. H., Jhonson, D. E. (1996). Management of organizational behavior. Utilizing human resources. Prentice Hall. 6th Edition. First published in 1969.</ref></li> | ||

<li>Four leadership styles (Likert)<ref></ref></li> | <li>Four leadership styles (Likert)<ref>Likert, R. (1967). The Human Organization. Its management and value. New York: McGraw-Hill.</ref></li> | ||

<li>Four leadership styles (Bass)<ref></ref></li> | <li>Four leadership styles (Bass)<ref>Bass B. M. (1990). Bass and Stogdill’s Handbook of Leadership: theory, research, and managerial application. New York: Free Press. First published in 1974.</ref></li> | ||

<li>Human resources role (Ulrich)<ref></ref></li> | <li>Human resources role (Ulrich)<ref>Ulrich, D. (1997). Human resource champions: the next agenda for adding value and delivering results. Boston: Harvard Business School Press</ref></li> | ||

<li>Teams’ dynamics (Kemp)<ref></ref></li> | <li>Teams’ dynamics (Kemp)<ref>Kemp, C. G. (1970). Perspectives on Group Process. A foundation for counselling with Groups. Boston, Houghton Mifflin. First published in 1964.</ref></li> | ||

<li>Organizational research (Scott)<ref></ref></li> | <li>Organizational research (Scott)<ref>Scott, W. R. (2003) Organizations : rational, natural and open systems. Upper Saddle River, N. J.: Prentice Hall.</ref></li> | ||

<li>Management styles (Blake & Mouton)<ref></ref></li> | <li>Management styles (Blake & Mouton)<ref>Blake R.R., Mouton J.S. (1987). The 3rd dimension of management. Organization editions. Translated from: The Managerial Grid III: the key to leadership excellence, 1964.</ref></li> | ||

<li>Psychoanalysis of Organizations (Kets de Vries and Miller)<ref></ref></li> | <li>Psychoanalysis of Organizations (Kets de Vries and Miller)<ref>Kets de Vries, M. F. R. (2000). The Clinical Paradigm: Manfred Kets De Vries’s Reflections on Organizational Therapy; An Interview by Erik van de Loo. European Management Journal. Vol 18, No; 1, p 2-21<br/>Kets de Vries, M. F. R., Miller, D. (1984). The Neurotic Organization : Diagnosing and Changing Counterproductive Styles of Management. San Francisco : Jossey-Bass.</ref></li> | ||

</ul> | </ul> | ||

| Line 110: | Line 109: | ||

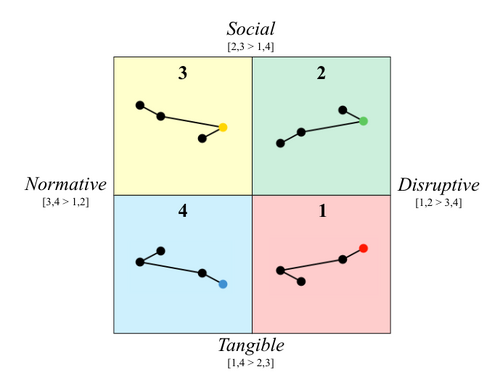

GRI’s grid emerged from the necessity to find correspondence between individual behaviors and behaviors found at other levels in positions, teams, and organizations at large, and other models that were showing similarities, as discussed above. The use of two dimensions and axes provided the most comprehensible way for establishing this correspondence. | GRI’s grid emerged from the necessity to find correspondence between individual behaviors and behaviors found at other levels in positions, teams, and organizations at large, and other models that were showing similarities, as discussed above. The use of two dimensions and axes provided the most comprehensible way for establishing this correspondence. | ||

[[File:Performance_Values_GRI_Grid.png|right|500px]] | |||

As for other comparable models, including the competing-value model, GRI’s grid is used for diagnosing performance at different levels and provides a first-level understanding of the behaviors, values, and preferences of people in groups. The behaviors associated with each model, human relations, open systems, internal processes, and rational goals, are correlated in behavioral terms with those represented in the adaptive profiles. | As for other comparable models, including the competing-value model, GRI’s grid is used for diagnosing performance at different levels and provides a first-level understanding of the behaviors, values, and preferences of people in groups. The behaviors associated with each model, human relations, open systems, internal processes, and rational goals, are correlated in behavioral terms with those represented in the adaptive profiles. | ||

<ul> | <ul> | ||

| Line 116: | Line 116: | ||

</ul> | </ul> | ||

The four models formed from these factor combinations are a simplified representation of four types of behaviors at a group level. The GRI typical profiles that illustrate the four dimensions are indicated | The four models formed from these factor combinations are a simplified representation of four types of behaviors at a group level. The GRI typical profiles that illustrate the four dimensions are indicated on the right. | ||

Although useful | Although useful for gaining an approximate overall understanding of behavioral values for a given group of people, a typology or grid is ineffective for other applications, including when needing to zoom in on a particular individual. This aspect is discussed below and reviewed in other articles dealing with those applications, for instance, organizational and leadership development or recruitment. | ||

=Beyond Grid Analyzes= | |||

Understanding that people show a vast range of behaviors, rather than only four types, and may require efforts to adapt, rather than adapting at will, calls for a more granular analysis and measures than what the four quadrants can tell. Notably: | Understanding that people show a vast range of behaviors, rather than only four types, and may require efforts to adapt, rather than adapting at will, calls for a more granular analysis and measures than what the four quadrants can tell. Notably: | ||

Teams and organizations require a specific set of behaviors. We call this the Team Behavior Indicator or TBI, which is made out of the same behavior factors as people, allowing for comparisons. | <ul> | ||

<li>Teams and organizations require a specific set of behaviors. We call this the Team Behavior Indicator or TBI, which is made out of the same behavior factors as people, allowing for comparisons.</li> | |||

Positions eventually require a specific set of behaviors beyond the TBI within the same team or organization. We call this the Position Behavior Indicator or PBI, which is made out of the same behavior factors as people and teams, allowing for comparisons. | <li>Positions eventually require a specific set of behaviors beyond the TBI within the same team or organization. We call this the Position Behavior Indicator or PBI, which is made out of the same behavior factors as people and teams, allowing for comparisons.</li> | ||

People’s behavior may show similarly or differently in a group, homogeneously or heterogeneously. We refer to it as quiet diversity, sometimes desirable, others not, depending on the context. | <li>People’s behavior may show similarly or differently in a group, homogeneously or heterogeneously. We refer to it as quiet diversity, sometimes desirable, others not, depending on the context.</li> | ||

</ul> | |||

How distant individual behaviors are from their positions and teams, being engaged or disengaged, will call for some adjustments within the organization and personal development to maximize individual and group performance. | How distant individual behaviors are from their positions and teams, being engaged or disengaged, will call for some adjustments within the organization and personal development to maximize individual and group performance. | ||

Although two dimensions are most of the time satisfactory for analyses at a team and organizational level, more refinements are needed when analyzing individuals, jobs, and the fit between the two, using then four factors rather than only two dimensions. A more granular representation of behavior values than what a 2x2 grid can allow will evidence whether the behaviors are opposed and eventually exclusive rather than complementing each other. | |||

Although two dimensions are most of the time satisfactory for analyses at a team and organizational level, more refinements are needed when analyzing individuals, jobs, and the fit between the two, using then four factors rather than only two dimensions. | |||

A more granular representation of behavior values than what a 2x2 grid can allow will evidence whether the behaviors are opposed and eventually exclusive rather than complementing each other. | |||

=Avoiding Contradictions, Clarifying Expectation= | =Avoiding Contradictions, Clarifying Expectation= | ||

| Line 140: | Line 137: | ||

As we evidence at GRI with the adaptive profiles, behaviors can conflict in an ever-changing environment. At times, conflicts can exceed tolerance thresholds that lead to reorganizations and a new, different perception of what constitutes success and performance. | As we evidence at GRI with the adaptive profiles, behaviors can conflict in an ever-changing environment. At times, conflicts can exceed tolerance thresholds that lead to reorganizations and a new, different perception of what constitutes success and performance. | ||

The identification and measurement of performance criteria begins with a series of value judgments that are usually conflicting and ends with what is essentially a political decision. In this context, a more precise understanding of the behavioral values that influence the decision | The identification and measurement of performance criteria begins with a series of value judgments that are usually conflicting and ends with what is essentially a political decision. In this context, a more precise understanding of the behavioral values that influence the decision helps clarify the potential performance of each stakeholder and what is expected from them and their organization. | ||

=References= | =References= | ||

Latest revision as of 13:54, 2 January 2026

Introduction

Performance models based on values extend stakeholder models by explaining organizational performance in terms of individual values and preferences. These models have become increasingly important in our research at GRI for analyzing performance[1], as they more closely address social behavior than other approaches.

At an individual level, values are typically defined as the fundamental principles, beliefs, and ideals a person considers essential in their life. Values are expressed, observed, and developed through social behavior.

At the organizational level, values are the core beliefs and principles an organization regards as essential for guiding its actions, decisions, and social behavior. In both cases, the concept of values encompasses broad aspects of social behavior that, unlike any other abstract concepts, can be observed, measured, and compared at different levels.

Generalities

Unlike other stakeholder approaches that focus on one specific variable and method with narrow applications, the approach of performance by values is broad, practical, and includes behaviors that can easily and objectively be described, measured, and shared. The framework is applicable to a variety of situations, stakeholders, and industries in different countries and cultures.

Behavioral values can be regrouped along two dimensions and represented in a 2x2 grid, which then provides a framework for analyzing how an organization and its members perform. Along those lines, the competing value model is the most thought-out model for the approach of performance based on values. It provides the foundational logic for its establishment and deployment, something that the GRI model greatly learned from.

However, the subjectivity of these two concepts of values and preferences is a significant obstacle. This is first reviewed below. Understanding that preferences and values typically compete opens up new ways to understand, manage, and enhance performance.

When discussing values, preferences, and behaviors, GRI’s terminology is included in this article within brackets for those already familiar with it, to help them understand this article. It will display, such as [High 1] or [High 4, with 4 higher than 3]. For others, please ignore.

Performance and Subjectivity

Unless being objectified, performance as a concept is primarily subjective, a challenge faced not only when being analyzed through individual preferences and values, but also through the objectives being set for the organization and its units, or through the stakeholders or constituencies of the organizations[2].

Studies conducted on the preferences of individuals and stakeholders are symptomatic of the problems posed by subjectivity when assessing performance. A major problem is that most people cannot identify their own preferences. What they usually report corresponds to their implicit theories or past behaviors that are plausible, but not to the preferences held by the individuals being assessed[3]. Research has evidenced a weak correlation between the knowledge of implicit preferences and motivational factors on one hand, and the preferences or actions that were selected as important from a behavioral standpoint on the other hand[4].

While trying to differentiate the 'theories in action' from the 'theories in use', another study found that the theories in people's minds do not correspond with the theories they put into action[5]. When lists of criteria are presented to individuals, this other study found it difficult to select the criteria that people consider important or those that are not[6]. Different techniques have been devised to solve the problem of identifying performance criteria, such as:

However, each of these techniques only serves to weigh a preference order. They rely on individuals’ ability to specify preferences with precision. They cannot ensure that the performance or effectiveness criteria identified a priori by individuals or implicitly held by them are the most important. Not only do people have difficulty identifying performance criteria, but their preference for a particular criterion can change over time[10]. The relationships between the criteria at two different times are unclear; in fact, performance in the past may not be a good predictor of effectiveness in the present and the future.

The Means for Reaching Objectives

The question of performance is a question of organizational necessity concerning objectives and means, but it also reflects the individual preferences, needs, or values of stakeholders. The analysis of performance by objectives and by the system converges in two situations. In one case, the objectives have been examined, and now the focus is on the means to achieve them. In the other case, when considering the means, it raises the question of what kind of objectives are needed and achievable.

Failure to achieve objectives then raises the question of the means that have not made it possible to achieve them. A variation of means calls into question the relevance of the objectives.

The dilemma between means and ends has been analyzed as a conflict between short and long-term perspectives[11]. It opens up for discussions and arbitration to a point that may be described as optimal[12].

At the organizational level, the notions of objectives and means are tightly linked. They are also linked to individuals' preferences or values. Both personally and organizationally, practical concerns arise to consider these two aspects together and as interdependent.

Competition Between Values

Several performance criteria can be seen as in competition or paradoxical rather than being compatible or congruent. To be effective and to exist, an organization must possess attributes that are, at the same time, all present and operate in concert, while being contradictory or even exclusive. For example, the following attributes are found simultaneously in organizations[13]:

- A weak coupling of attributes that encourages initiative, innovation, and functional autonomy [Low 3, high 1, low 4], at the same time as a strong coupling of attributes that encourages rapid execution, the implementation of innovation, and functional reciprocity [low 3, low 1, high 4].

- The high specialization of roles, which reinforces expertise and efficiency [low 3, high 4], as well as the generalist roles, which reinforce flexibility and interdependence [1 higher than 4, Low 1].

- The continuity of leadership, which allows stability, long-term planning, and institutional memory [high 4, high 3, low 1], at the same time as the recruitment of new leaders, which allows for increased innovation and adaptability [high 1, low 4].

- Processes of amplifying deviant phenomena that encourage productive conflicts and energizing productive oppositions for the organization [high 1], as well as processes of reducing deviant phenomena that encourage the need for harmony and consensus to generate trust and circulate information [low 1, high 2].

- Increased research to make decisions that allow access to more information, increased presence, varied sources of stimulation [low 3, high 2], as well as the creation of inhibitors to stop the information overload that reduces the amount of information for decision-makers and leads to convergence in decision-making [low 2].

- The disengagement from past strategies which allowed for the emergence of new perspectives and innovation, and focusses the definition of new problems [high 1, Low 4], to variations of old problems, as well as the reintegration and reinforcement of the basic aspects that consolidate the adhesion to the specific corporate identity, mission, and strategies from the past [high 2, high 4, low 1].

The Competing Value Models

In response to the problems posed by the competition and paradox between performance criteria, the performance model based on competing values offers a synthesis of the possible links between an organization's preferences/values and those of its stakeholders[14].

The starting point of the competing values models is the arrangement of about thirty criteria evaluated by a group of experts using multivariate techniques. These criteria are those that overlap several studies aimed at assessing an organization’s performance. The result is a ranking of performance values along three dimensions:

- Structure: flexible versus control

- Focus: external versus internal

- Practical: Means versus Ends

The first dimension, Structure, contrasts with the dimensions of control and flexibility. While some scholars value authority, structure, coordination, control, formalization, and integration [low 1, low 2, high 3, high 4], others prioritize diversity, individual initiative, spontaneity, flexibility, and organizational adaptability [high 1, high 2, low 3, low 4]. The difference between mechanistic and bureaucratic organizations and entrepreneurial organizations lies in this opposition between control and flexibility.

The "Focus" dimension contrasts internal and external approaches within stakeholder models. These two competing values are fundamental to an organization’s existence. With an External focus, the organization functions as a logically structured tool aimed at acquiring resources and achieving goals. The focus is on maintaining the organization’s competitiveness in a dynamic environment [low 1, high 2, high 3, low 4]. Conversely, with an Internal focus, the organization is seen as a socio-technical system. Its members have unique feelings, interests, preferences, and values that must be considered within their work environment [high 1, low 2, low 3, high 4]. While the internal focus addresses micro-level aspects, the external focus emphasizes macro-level aspects.

As discussed above, the dimension that opposes means to ends refers to the approaches of objectives and systems. Organizations strive to achieve goals through the management of both animated (people) and inanimate (things) means that help them reach their objectives, especially those means that become functionally autonomous, i.e., that function as organizational objectives[15]. This third component of means-ends was later integrated into the other two dimensions: Flexibility/Control and Internal/External[16]. These last two dimensions sufficiently account for the four models of organizational performance represented on the right.

- The human relations model places importance on flexibility and internal aspects. It emphasizes criteria such as those indicated in the upper left-hand corner: cohesion, morale, and human resource development.

- The open system model places importance on flexibility and externalities, emphasizing flexibility, responsiveness, growth, acquisition of external resources, and support.

- The rational goal model focuses on controlling and outward planning, goal setting, productivity, and efficiency.

- The internal process model places importance on information management, communication, stability, and control. This model imposes an organized work situation with sufficient coordination and distribution of information to provide actors with a sense of continuity and security.

In the competing values framework, the models of rational goals and internal processes are not as distinctly differentiated from each other as are the different models. The most distant models are across the diagonal, between the rational goals model, compared to the human relations on one hand, and between the open systems contrasted with the internal processes on the other.

By facilitating an analysis of both the objectives to be achieved and the means to be pursued, the values model can be considered the most comprehensive analytical framework for analyzing and assisting in developing performance. The framework enables articulating practical actions in organizations by considering both the means and the objectives, allowing intervention methods to analyze potential shortcomings and optimize the organization's functioning[17].

Extending Grid Analysis to Other Models

The competing value model can be compared to other models that operate at different levels and for various applications, but nevertheless use similar dimensions, enabling the comparison of human dynamics and how stakeholders connect with the organization at these different levels.

This includes the AGIL framework elaborated at a societal level by Parsons and Shils[18], where the two axes of analysis are closely aligned. The adaptive functions (A) parallel the open systems model, the goal attainment functions (G) align with the rational goals model, the integration functions (I) compare with the internal processes model, and the latency and maintenance functions (L) relate to the human relations model.

Analyzing organizations as dynamic systems, Katz and Kahn's open systems model[19] presents a classification based on functions along two axes: internal vs. external, and Economical/instrumental vs. political/integrative. The adaptive category parallels the open systems model, the productive category aligns with the rational goals model, the maintenance category compares with the internal processes model, and the integrative category relates to the human relations model.

Other models have used a similar 2x2 grid representation with two comparable axes, but for covering different topics than the above, including the following:

- Situational leadership (Hersey, Blanchard & Johnson)[20]

- Four leadership styles (Likert)[21]

- Four leadership styles (Bass)[22]

- Human resources role (Ulrich)[23]

- Teams’ dynamics (Kemp)[24]

- Organizational research (Scott)[25]

- Management styles (Blake & Mouton)[26]

- Psychoanalysis of Organizations (Kets de Vries and Miller)[27]

The competing value model also provides comparable grids for analyzing managers, companies' units, development, and industries. All models include behaviors that are broadly found in individuals and organizations. The two axes and the 2x2 grids allow for the comparison of behaviors between models and a comprehensive description of stakeholders and organizations that can then be used to analyze their performance.

Extending the Grid Analysis to GRI

GRI’s grid emerged from the necessity to find correspondence between individual behaviors and behaviors found at other levels in positions, teams, and organizations at large, and other models that were showing similarities, as discussed above. The use of two dimensions and axes provided the most comprehensible way for establishing this correspondence.

As for other comparable models, including the competing-value model, GRI’s grid is used for diagnosing performance at different levels and provides a first-level understanding of the behaviors, values, and preferences of people in groups. The behaviors associated with each model, human relations, open systems, internal processes, and rational goals, are correlated in behavioral terms with those represented in the adaptive profiles.

- The vertical dimension Flexibility/Control corresponds to the factors 2 and 3 of the GRI, being both high or low.

- The horizontal dimension External/Internal corresponds to the factors 1 and 4 of the GRI, being both high or low.

The four models formed from these factor combinations are a simplified representation of four types of behaviors at a group level. The GRI typical profiles that illustrate the four dimensions are indicated on the right.

Although useful for gaining an approximate overall understanding of behavioral values for a given group of people, a typology or grid is ineffective for other applications, including when needing to zoom in on a particular individual. This aspect is discussed below and reviewed in other articles dealing with those applications, for instance, organizational and leadership development or recruitment.

Beyond Grid Analyzes

Understanding that people show a vast range of behaviors, rather than only four types, and may require efforts to adapt, rather than adapting at will, calls for a more granular analysis and measures than what the four quadrants can tell. Notably:

- Teams and organizations require a specific set of behaviors. We call this the Team Behavior Indicator or TBI, which is made out of the same behavior factors as people, allowing for comparisons.

- Positions eventually require a specific set of behaviors beyond the TBI within the same team or organization. We call this the Position Behavior Indicator or PBI, which is made out of the same behavior factors as people and teams, allowing for comparisons.

- People’s behavior may show similarly or differently in a group, homogeneously or heterogeneously. We refer to it as quiet diversity, sometimes desirable, others not, depending on the context.

How distant individual behaviors are from their positions and teams, being engaged or disengaged, will call for some adjustments within the organization and personal development to maximize individual and group performance.

Although two dimensions are most of the time satisfactory for analyses at a team and organizational level, more refinements are needed when analyzing individuals, jobs, and the fit between the two, using then four factors rather than only two dimensions. A more granular representation of behavior values than what a 2x2 grid can allow will evidence whether the behaviors are opposed and eventually exclusive rather than complementing each other.

Avoiding Contradictions, Clarifying Expectation

Judging an organization’s performance involves questions of behavioral values, preferences, and interests. Selecting some behaviors for an organization tends to impose a particular perspective, potentially obscuring other behaviors. Looking at behavioral values in groups invites considering the possible contradictions in each organization. The arbitration at play should be seen as a dynamic process, not a static one.

As we evidence at GRI with the adaptive profiles, behaviors can conflict in an ever-changing environment. At times, conflicts can exceed tolerance thresholds that lead to reorganizations and a new, different perception of what constitutes success and performance.

The identification and measurement of performance criteria begins with a series of value judgments that are usually conflicting and ends with what is essentially a political decision. In this context, a more precise understanding of the behavioral values that influence the decision helps clarify the potential performance of each stakeholder and what is expected from them and their organization.

References

- ↑ See here an overview of performance models.

- ↑ Van de Ven, A. H., Ferry, D. (1980). Measuring and Assessing organizations. New York: Wiley.

Bluedorn, A. C. (1980). Cutting the Gordian knot: A critique of the effectiveness tradition in organizational research. Sociology and Social Research, 64, 477-496

Connoly, T., Colon E. M., Deutch, S. J. (1980). Organizational effectiveness: a multiple constituency approach. Academy of Management review, 5, 211-218. - ↑ Nisbet, R. E., Wilson, T. (1977). Telling more than we can know: Verbal reports on mental processes; Psychological Review, 134, 231-259.

- ↑ Slovic, P., Lichtenstein, S. (1971). Comparison of Bayesian and regression approaches to the study of information processing in judgement. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 6, 649-744.

- ↑ Argyris, C, Schon, D. (1978). Organizational learning: A theory of action perspective. Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley.

- ↑ Gross, E., Grambsch, P. V. (1968). University goals and academic power. Washington, D. C.: American Council on Education.

- ↑ Hammond, K. R., McClelland, G. H., Mumpower, J. (1980) Human judgement and decision making: Theories, methods, and procedures. New York : Praeger.

- ↑ Delbecq, A. L, Van de Ven, A. H., Gustafson, D. H. (1975). Group techniques for program planning. Glenview, Ill.: Scott Foresman.

- ↑ Huber, G. P. (1974). Methods for quantifying subjective probabilities and multi-attribute utilities. Decision Sciences, 5, 3-31.

- ↑ McDonald, J. (1975). The game of business. Garden City, N.Y.: Anchor Press.

Quinn, R. E., Cameron, K. S. (1982). Life cycles and shifting criteria of effectiveness: Some preliminary evidence. Management Science, 27.

Miles, R. H., Cameron, K. S. (1982). Coffin nails and corporate strategies. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall. - ↑ Lawrence, P. R., Lorsch, J. W. (1967). Organization and Environment. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

- ↑ Katz D., Kahn, R.L. (1978). The social psychology of organization. New York: Willey. Originally published in 1966.

- ↑ Cameron, K. S. (1986). Effectiveness as Paradox: Consensus and Conflict in Conceptions of Organizational Effectiveness. Vol. 32, No. 5, pp 539-553.

- ↑ Quinn, R. E., Rohrbaugh J. (1983). A Spatial Model of Effectiveness Criteria: towards a Competing Values Approach to Organizational Analysis. Management Science. Vol. 29, No. 3, pp. 363-377.

- ↑ Georgopoulos, B. S., Tannenbaum, A. S. (1957). A study of Organizational Effectiveness. American Sociological Review, 22, 534-540.

- ↑ Quinn, R. E. (1988) Beyond rational management. Mastering the Paradoxes and Competing Demands of High Performance. San Francisco, California, Jossey-Bass.

- ↑ Quinn, R. E. (1988) Beyond rational management. Mastering the Paradoxes and Competing Demands of High Performance. San Francisco, California, Jossey Bass.

- ↑ Parsons, T., Shils, E. A. (2001). Toward a general theory of action.: theoretical foundations for the social science. New York: The Free Press. First published in 1951.

- ↑ Katz D., Kahn, R.L. (1978). The social psychology of organization. New York: Wiley & Sons. Originally published in 1966.

- ↑ Hersey, P., Blanchard, K. H., Jhonson, D. E. (1996). Management of organizational behavior. Utilizing human resources. Prentice Hall. 6th Edition. First published in 1969.

- ↑ Likert, R. (1967). The Human Organization. Its management and value. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- ↑ Bass B. M. (1990). Bass and Stogdill’s Handbook of Leadership: theory, research, and managerial application. New York: Free Press. First published in 1974.

- ↑ Ulrich, D. (1997). Human resource champions: the next agenda for adding value and delivering results. Boston: Harvard Business School Press

- ↑ Kemp, C. G. (1970). Perspectives on Group Process. A foundation for counselling with Groups. Boston, Houghton Mifflin. First published in 1964.

- ↑ Scott, W. R. (2003) Organizations : rational, natural and open systems. Upper Saddle River, N. J.: Prentice Hall.

- ↑ Blake R.R., Mouton J.S. (1987). The 3rd dimension of management. Organization editions. Translated from: The Managerial Grid III: the key to leadership excellence, 1964.

- ↑ Kets de Vries, M. F. R. (2000). The Clinical Paradigm: Manfred Kets De Vries’s Reflections on Organizational Therapy; An Interview by Erik van de Loo. European Management Journal. Vol 18, No; 1, p 2-21

Kets de Vries, M. F. R., Miller, D. (1984). The Neurotic Organization : Diagnosing and Changing Counterproductive Styles of Management. San Francisco : Jossey-Bass.