Disruptive vs Normative Behaviors: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

|||

| (6 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[File:Performance_Individual.png|right| | [[File:Performance_Individual.png|right|400px]] | ||

This article aims to | This article aims to provide some information on two fundamental tendencies that can be read from the adaptive profiles: normative behaviors versus disruptive behaviors. It contains GRI's terminology that requires a basic understanding of the adaptive profiles<ref>[[Performance_at_Heart|See here for a brief definition of an adaptive profile and some key concepts it contains.]]</ref>. | ||

=Generalities= | =Generalities= | ||

Behaviors that characterize how we communicate, socialize, and interact can be analyzed through a limited number of factors<ref>Saucier, G. (2003). An Alternative Multi-language Structure for Personality Attributes. European Journal of Personality. Vol. 17, p. 179-205.</ref>. This result comes from work initially undertaken by Allport & Allport<ref>Allport F. H., Allport G. W. (1921). Personality Traits: their classification and measurement. The Journal of Abnormal Psychology and Social Psychology. Vol 16., p 7-40.</ref>, Thurstone<ref>Thurstone L. L. (1934). The Vectors of Mind. Psychological Review, Vol. 41, p. 1-32.<br/>Thurstone L. L. (1959). The measurement of Values. The University of Chicago Press.</ref>, Allport & Odbert<ref>Allport, G. W., & Odbert, H. S. (1936). Trait names: A psycho-lexical study. Psychological Monographs, 47, 1–171.</ref>, and others who researched adjective lexicons and the concept of personality. Factor analysis leads to a relatively small number of transposable factors between cultures for describing behavior. | Behaviors that characterize how we communicate, socialize, and interact can be analyzed through a limited number of factors<ref>Saucier, G. (2003). An Alternative Multi-language Structure for Personality Attributes. European Journal of Personality. Vol. 17, p. 179-205.</ref>. This result comes from work initially undertaken by Allport & Allport<ref>Allport F. H., Allport G. W. (1921). Personality Traits: their classification and measurement. The Journal of Abnormal Psychology and Social Psychology. Vol 16., p 7-40.</ref>, Thurstone<ref>Thurstone L. L. (1934). The Vectors of Mind. Psychological Review, Vol. 41, p. 1-32.<br/>Thurstone L. L. (1959). The measurement of Values. The University of Chicago Press.</ref>, Allport & Odbert<ref>Allport, G. W., & Odbert, H. S. (1936). Trait names: A psycho-lexical study. Psychological Monographs, 47, 1–171.</ref>, and others who researched adjective lexicons and the concept of personality. Factor analysis leads to a relatively small number of transposable factors between cultures for describing behavior. | ||

The four factors measured by GRI, called factors 1, 2, 3, and 4<ref>The factors are purposely called by numbers to avoid biases and misunderstandings attached to labelling</ref>, can be compared with the findings from Marston<ref>Marston W. M. (2002. Emotions of Normal People. Routledge. First published in 1928.</ref>, Burt<ref>Burt, C. L. (1950). The factorial study of emotions. In M. L. Reymert, Ed., Feelings and Emotions. New York: McGraw-Hill. Pp. 531-551.</ref>, and Clarke<ref>Clarke W. V. (1956). Personality Profile of Self-Made Company Presidents. The Journal of Psychology. 41, p. 413-418.</ref> on the feelings and emotions of normal people. These factors also align with the dimensions identified in sociological studies, such as those of Parsons<ref>Parsons T. (1951). The Social System. New York: The Free Press.<br/>Parsons T. (1964). Social structure and personality. New York: The Free Press.</ref>, Parsons & Shils<ref>Parsons, T., Shils, E. A. (2001). Toward a general theory of action.: theoretical foundations for the social science. New York: The Free Press. First published in 1951.</ref>, and Katz & Khan<ref>Katz D., Kahn, R. L. (1978). The social psychology of organization. New York: Wiley. Originellement publié en 1966.</ref>. They were evidenced by studies on the five-factor approach conducted by Goldberg<ref>Goldberg, L. R. (1990). An alternative "description of personality": The Big-Five factor structure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59, 1216-1229.</ref>, Costa & McCrae<ref>Costa P. T., McCrae R. R. (1992). Four ways five factors are basic. Personality and Individual Differences, Vol. 13, p. 653-665.</ref>, Saucier, Thalmayer, and Payne<ref>Saucier, G., Thalmayer A. G., Payne D. L. (2010). A Basic Bivariate Structure of Personality Attributes Evident Across Nine Languages. Unpublished.</ref>, and other more recent studies on the optimal number of personality factors<ref>De Raad, B., Barelds, D. P. H., Timmerman, M. E., de Roover, K., Mlačić, B., Church, A. T. (2014). Towards a Pan-cultural Personality Structure: Input from 11 psychological Studies. European Journal of Personality, 28, 497-510.</ref>. | The four factors measured by GRI, called factors 1, 2, 3, and 4<ref>The factors are purposely called by numbers to avoid biases and misunderstandings attached to labelling. [[Operationalizing_Performance | See here for basic information about the adaptive profiles.]]</ref>, can be compared with the findings from Marston<ref>Marston W. M. (2002. Emotions of Normal People. Routledge. First published in 1928.</ref>, Burt<ref>Burt, C. L. (1950). The factorial study of emotions. In M. L. Reymert, Ed., Feelings and Emotions. New York: McGraw-Hill. Pp. 531-551.</ref>, and Clarke<ref>Clarke W. V. (1956). Personality Profile of Self-Made Company Presidents. The Journal of Psychology. 41, p. 413-418.</ref> on the feelings and emotions of normal people. These factors also align with the dimensions identified in sociological studies, such as those of Parsons<ref>Parsons T. (1951). The Social System. New York: The Free Press.<br/>Parsons T. (1964). Social structure and personality. New York: The Free Press.</ref>, Parsons & Shils<ref>Parsons, T., Shils, E. A. (2001). Toward a general theory of action.: theoretical foundations for the social science. New York: The Free Press. First published in 1951.</ref>, and Katz & Khan<ref>Katz D., Kahn, R. L. (1978). The social psychology of organization. New York: Wiley. Originellement publié en 1966.</ref>. They were evidenced by studies on the five-factor approach conducted by Goldberg<ref>Goldberg, L. R. (1990). An alternative "description of personality": The Big-Five factor structure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59, 1216-1229.</ref>, Costa & McCrae<ref>Costa P. T., McCrae R. R. (1992). Four ways five factors are basic. Personality and Individual Differences, Vol. 13, p. 653-665.</ref>, Saucier, Thalmayer, and Payne<ref>Saucier, G., Thalmayer A. G., Payne D. L. (2010). A Basic Bivariate Structure of Personality Attributes Evident Across Nine Languages. Unpublished.</ref>, and other more recent studies on the optimal number of personality factors<ref>De Raad, B., Barelds, D. P. H., Timmerman, M. E., de Roover, K., Mlačić, B., Church, A. T. (2014). Towards a Pan-cultural Personality Structure: Input from 11 psychological Studies. European Journal of Personality, 28, 497-510.</ref>. | ||

=Disruptive Behaviors= | =Disruptive Behaviors= | ||

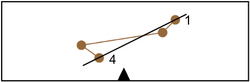

For these disruptive behaviors, the profiles show a high factor 1 (to the right), a low factor 4 (to the left) lower than factor 1 (to the left of factor 1). Cf. Figure 1. | For these disruptive behaviors, the profiles show a high factor 1 (to the right), a low factor 4 (to the left) lower than factor 1 (to the left of factor 1). Cf. Figure 1. | ||

[[File:Disruptive Profile.png|center| | [[File:Disruptive Profile.png|center|250px]] | ||

<center>''Figure 1 - Disruptive Behavior.''</center> | <center>''Figure 1 - Disruptive Behavior.''</center> | ||

| Line 31: | Line 29: | ||

These behaviors also correspond to personal efficacy in situations of change<ref>Hill, T., Smith, N. D., Mann, M. F. (1987). Role of self-efficacy expectations in predicting the decision to use advanced technologies: The case of computers. Journal of Applied Psychology, 72 (2), 307-313.</ref>, in environments where it is necessary to resist in order to accept negative feedback<ref>Nease A., Mudget B., Quinones M. (1999). Relationships among feedback sign, self-efficacy, and acceptance of performance feedback. Journal of Applied Psychology. Vol. 84, No. 5, p 806-814.</ref>, or in situations where it is necessary to show persistence in order to perform over time in the face of adversity<ref>Lent, R. W., Brown, S. D., Larkin, K. C. (1987). Comparison of three theoretically-derived variables predicting career and academic behaviour: Self-efficacy, interest congruence, and consequential thinking. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 34, 293-298.</ref> or to demonstrate stronger-than-average performance<ref>Luthans F., Stajkovic A., Luthans B. C., Luthans K. W. (1998). Applying Behavioral Management in Eastern Europe. European Management Journal. Vol. 16, No. 4, p. 466-475.</ref>. Disruptive behavior is partially located in the Extraversion and Neuroticism dimensions and inversely in the Agreeable and Conscientious dimensions of the five-factor approach, without an exact correspondence, particularly regarding the clinical aspects of the dimensions, which are out of focus for GRI. | These behaviors also correspond to personal efficacy in situations of change<ref>Hill, T., Smith, N. D., Mann, M. F. (1987). Role of self-efficacy expectations in predicting the decision to use advanced technologies: The case of computers. Journal of Applied Psychology, 72 (2), 307-313.</ref>, in environments where it is necessary to resist in order to accept negative feedback<ref>Nease A., Mudget B., Quinones M. (1999). Relationships among feedback sign, self-efficacy, and acceptance of performance feedback. Journal of Applied Psychology. Vol. 84, No. 5, p 806-814.</ref>, or in situations where it is necessary to show persistence in order to perform over time in the face of adversity<ref>Lent, R. W., Brown, S. D., Larkin, K. C. (1987). Comparison of three theoretically-derived variables predicting career and academic behaviour: Self-efficacy, interest congruence, and consequential thinking. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 34, 293-298.</ref> or to demonstrate stronger-than-average performance<ref>Luthans F., Stajkovic A., Luthans B. C., Luthans K. W. (1998). Applying Behavioral Management in Eastern Europe. European Management Journal. Vol. 16, No. 4, p. 466-475.</ref>. Disruptive behavior is partially located in the Extraversion and Neuroticism dimensions and inversely in the Agreeable and Conscientious dimensions of the five-factor approach, without an exact correspondence, particularly regarding the clinical aspects of the dimensions, which are out of focus for GRI. | ||

=Normative | =Normative Behaviors= | ||

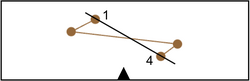

For these normative behaviors, factor 4 is high (to the right of the profile), and factor 1 is low (to the left of the profile) and higher than factor 1 (to the right of factor 1). See Figure 3 below. | For these normative behaviors, factor 4 is high (to the right of the profile), and factor 1 is low (to the left of the profile) and higher than factor 1 (to the right of factor 1). See Figure 3 below. | ||

[[File:Normative Profile.png|center| | [[File:Normative Profile.png|center|250px]] | ||

<center>''Figure 3 – Normative Behavior''</center> | <center>''Figure 3 – Normative Behavior''</center> | ||

Latest revision as of 22:02, 31 August 2025

This article aims to provide some information on two fundamental tendencies that can be read from the adaptive profiles: normative behaviors versus disruptive behaviors. It contains GRI's terminology that requires a basic understanding of the adaptive profiles[1].

Generalities

Behaviors that characterize how we communicate, socialize, and interact can be analyzed through a limited number of factors[2]. This result comes from work initially undertaken by Allport & Allport[3], Thurstone[4], Allport & Odbert[5], and others who researched adjective lexicons and the concept of personality. Factor analysis leads to a relatively small number of transposable factors between cultures for describing behavior.

The four factors measured by GRI, called factors 1, 2, 3, and 4[6], can be compared with the findings from Marston[7], Burt[8], and Clarke[9] on the feelings and emotions of normal people. These factors also align with the dimensions identified in sociological studies, such as those of Parsons[10], Parsons & Shils[11], and Katz & Khan[12]. They were evidenced by studies on the five-factor approach conducted by Goldberg[13], Costa & McCrae[14], Saucier, Thalmayer, and Payne[15], and other more recent studies on the optimal number of personality factors[16].

Disruptive Behaviors

For these disruptive behaviors, the profiles show a high factor 1 (to the right), a low factor 4 (to the left) lower than factor 1 (to the left of factor 1). Cf. Figure 1.

Factor 1 expresses the need to have authority and influence people and events. People with a high factor 1 are confident, independent, innovative, and enterprising. People with a very high 1 can be perceived as arrogant, egocentric, or belligerent. A High 1 needs a competitive environment that rewards entrepreneurship and the ability to take on challenges.

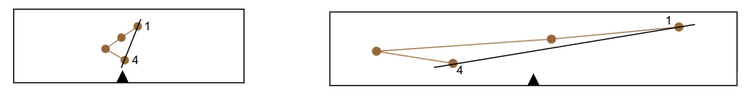

Unlike High 4s (see below with Normative behavior), a Low 4 is seen as casual, independent, carefree, or unabashed. A very Low 4 can be seen as rebellious, unruly, disrespectful, and neglectful. Low 4s need little structure and few rules. The wider the profile, the more the disruptive behaviors described above are evidently expressed. Conversely, the narrower the profile, the fewer disruptive behaviors described above are observed (Cf. Figure 2).

Entrepreneurs and change agent leaders have disruptive profiles as they strongly need to leave an imprint on discussions, decisions, and their environment. The authoritarian behaviors described by Adler[17] and Adorno[18] are part of this disruptive tendency. They also correspond to those of the β factor of the approach with two theoretical constructs or meta-features of Digman[19] found in numerous studies, including that of Hogan, with the notion of popularity.[20]

Personal innovation or the will to change[21], along with a high-risk tolerance[22], are characteristics of these profiles. By being spontaneously inclined to take risks, these people also engage more spontaneously in innovative, disruptive behaviors[23], such as technological innovations[24].

These behaviors also correspond to personal efficacy in situations of change[25], in environments where it is necessary to resist in order to accept negative feedback[26], or in situations where it is necessary to show persistence in order to perform over time in the face of adversity[27] or to demonstrate stronger-than-average performance[28]. Disruptive behavior is partially located in the Extraversion and Neuroticism dimensions and inversely in the Agreeable and Conscientious dimensions of the five-factor approach, without an exact correspondence, particularly regarding the clinical aspects of the dimensions, which are out of focus for GRI.

Normative Behaviors

For these normative behaviors, factor 4 is high (to the right of the profile), and factor 1 is low (to the left of the profile) and higher than factor 1 (to the right of factor 1). See Figure 3 below.

A high 4 expresses the propensity to conform to rules and structures, the opposite of being informal and uninhibited when factor 4 is low. This factor accentuates the need for details and rules. A very High factor 4 can be perceived as inflexible and anxious to do everything perfectly.

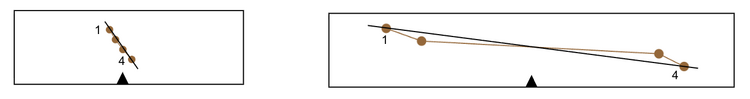

Unlike High 1s, Low 1s are modest, devoted, and even discreet. When factor 1 is very low, the person can be seen as docile and withdrawn. A Low 1 prefers to work with a team and in an environment free of conflicts. The wider this profile, the more the normative behaviors are intensely expressed. Conversely, the narrower the profile, the more the normative behaviors are difficult to evidence. See figure 4 below.

The characteristics of the normative profile are close to those described in the literature for the conscientiousness dimension of the five-factor approach. People with these profiles are disciplined, organized, task-oriented, and rule-bound. This dimension has shown links with performance in structured environments where ambiguity, uncertainty, and rapid adaptation to change are absent[29].

We also find the Agreeableness dimension of the five-factor approach in this normative profile. According to this dimension, people are kind, cooperative, generous, and courteous. They are loyal. Positive relationships between performance have been demonstrated with the two factors, Conscientiousness and Agreeableness, in positions requiring frequent interaction and cooperation[30]. The Agreeableness dimension of the five-factor approach showed a strong link with the propensity to be positive, to be engaged in conversations other than those relating to work, and to provide empathetic support to others on an emotional level. These conversations tend to reinforce the personal values of others[31].

This normative profile matches the descriptions of the α dimension described by Digman[32], as opposed to the β dimension of the above disruptive profile. The α dimension suggests a strong social desirability to say socially acceptable things about oneself and others. The normative profile portrays socially acceptable behaviors. Unlike hostility, an undesirable social trait, kindness, conscientiousness, containing impulses, and containing aggressiveness have always been subject to rules of social conduct.

Notes

- ↑ See here for a brief definition of an adaptive profile and some key concepts it contains.

- ↑ Saucier, G. (2003). An Alternative Multi-language Structure for Personality Attributes. European Journal of Personality. Vol. 17, p. 179-205.

- ↑ Allport F. H., Allport G. W. (1921). Personality Traits: their classification and measurement. The Journal of Abnormal Psychology and Social Psychology. Vol 16., p 7-40.

- ↑ Thurstone L. L. (1934). The Vectors of Mind. Psychological Review, Vol. 41, p. 1-32.

Thurstone L. L. (1959). The measurement of Values. The University of Chicago Press. - ↑ Allport, G. W., & Odbert, H. S. (1936). Trait names: A psycho-lexical study. Psychological Monographs, 47, 1–171.

- ↑ The factors are purposely called by numbers to avoid biases and misunderstandings attached to labelling. See here for basic information about the adaptive profiles.

- ↑ Marston W. M. (2002. Emotions of Normal People. Routledge. First published in 1928.

- ↑ Burt, C. L. (1950). The factorial study of emotions. In M. L. Reymert, Ed., Feelings and Emotions. New York: McGraw-Hill. Pp. 531-551.

- ↑ Clarke W. V. (1956). Personality Profile of Self-Made Company Presidents. The Journal of Psychology. 41, p. 413-418.

- ↑ Parsons T. (1951). The Social System. New York: The Free Press.

Parsons T. (1964). Social structure and personality. New York: The Free Press. - ↑ Parsons, T., Shils, E. A. (2001). Toward a general theory of action.: theoretical foundations for the social science. New York: The Free Press. First published in 1951.

- ↑ Katz D., Kahn, R. L. (1978). The social psychology of organization. New York: Wiley. Originellement publié en 1966.

- ↑ Goldberg, L. R. (1990). An alternative "description of personality": The Big-Five factor structure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59, 1216-1229.

- ↑ Costa P. T., McCrae R. R. (1992). Four ways five factors are basic. Personality and Individual Differences, Vol. 13, p. 653-665.

- ↑ Saucier, G., Thalmayer A. G., Payne D. L. (2010). A Basic Bivariate Structure of Personality Attributes Evident Across Nine Languages. Unpublished.

- ↑ De Raad, B., Barelds, D. P. H., Timmerman, M. E., de Roover, K., Mlačić, B., Church, A. T. (2014). Towards a Pan-cultural Personality Structure: Input from 11 psychological Studies. European Journal of Personality, 28, 497-510.

- ↑ Adler, A. (1939). Social interest. New York: Putnam.

- ↑ Adorno T. W. and others (1950). The authoritarian personality, New York, Harper.

- ↑ Ibid, Digman, 1997.

- ↑ Ibid, Hogan, 1982.

- ↑ Hurt, H. T., Joseph, K., Cooed, C. D. (1997). Scales for the measurement of innovativeness. Human Communication Research, 4, 58-65

- ↑ Bommer, M., Jalajas, D. S. (1999). The threat of organizational downsizing on the innovative propensity of R&D professionals. R & D Management, 29, 27-34.

- ↑ Agarwal, R., Prasad, J. (1998). The antecedents and consequences of user perceptions in information technology adoption. Decision Support Systems, 22, 15-29.

- ↑ Thatcher, J. B., Perrewé, P. L. (2000). An empirical examination of computer self-efficacy: The role of personality and anxiety. Presented at the Southern Management Association Meetings Proceedings, Orlando, FL.

Agarwal, R., Prasad, J. (1998). A conceptual and operational definition of personal innovativeness in the domain of information technology. Information Systems Research, 9, 204-215. - ↑ Hill, T., Smith, N. D., Mann, M. F. (1987). Role of self-efficacy expectations in predicting the decision to use advanced technologies: The case of computers. Journal of Applied Psychology, 72 (2), 307-313.

- ↑ Nease A., Mudget B., Quinones M. (1999). Relationships among feedback sign, self-efficacy, and acceptance of performance feedback. Journal of Applied Psychology. Vol. 84, No. 5, p 806-814.

- ↑ Lent, R. W., Brown, S. D., Larkin, K. C. (1987). Comparison of three theoretically-derived variables predicting career and academic behaviour: Self-efficacy, interest congruence, and consequential thinking. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 34, 293-298.

- ↑ Luthans F., Stajkovic A., Luthans B. C., Luthans K. W. (1998). Applying Behavioral Management in Eastern Europe. European Management Journal. Vol. 16, No. 4, p. 466-475.

- ↑ LePine, J. A., Colquitt, J. A., Erez, A. (2000). Adaptability to changing task contexts: Effects of general cognitive ability, consciousness, and openness to experience. Personnel Psychology, 53, 563-593.

- ↑ Witt, L. A., Burke, L. A., Barrick, M. R., Mount, M. K. (2002). The interactive effects of conscientiousness and agreeableness on job performance. Journal of Applied Psychology. Vol. 87. No. 1. p. 164-169.

- ↑ Zellars, K. L., Perrewé, P. L. (2001). Affective personality and the content of emotional social support: Coping in organizations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 459-467.

- ↑ Ibid, Digman, 1997.