Hypotheses Formulation: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[File:GRI Model_detailed.png|right|350px]] | |||

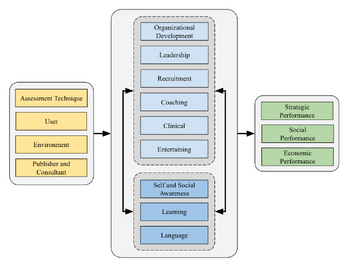

The hypotheses of the general framework were formulated to answer the specific question on the relationship between the “Use of assessment techniques” and “Performance”. The operational content of the theoretical concepts "Use of assessment technique" was clarified during the analysis of the uses by considering nine categories: “Organizational Development”, “Leadership”, “Recruitment”, “Coaching”, “Clinical”, “Entertaining”, “Self and Social Awareness”, “Learning,” and “Language”. | The hypotheses of the general framework were formulated to answer the specific question on the relationship between the “Use of assessment techniques” and “Performance”. The operational content of the theoretical concepts "Use of assessment technique" was clarified during the analysis of the uses by considering nine categories: “Organizational Development”, “Leadership”, “Recruitment”, “Coaching”, “Clinical”, “Entertaining”, “Self and Social Awareness”, “Learning,” and “Language”. | ||

Revision as of 16:23, 23 September 2025

The hypotheses of the general framework were formulated to answer the specific question on the relationship between the “Use of assessment techniques” and “Performance”. The operational content of the theoretical concepts "Use of assessment technique" was clarified during the analysis of the uses by considering nine categories: “Organizational Development”, “Leadership”, “Recruitment”, “Coaching”, “Clinical”, “Entertaining”, “Self and Social Awareness”, “Learning,” and “Language”.

To operationally define the relationship between the “Use of assessment techniques” and “Performance,” we say that there is agreement when, over time, performance increases, while the “Use of assessment techniques” increases too. Conversely, there is disagreement when the performance decreases or does not change, while the “Use of the assessment technique” increases.

The confrontation between the concepts of “Use of assessment technique” constructed inductively and the literature (obtained deductively) forms provisional refutable and confirmable hypotheses to be tested[1]. The hypotheses are formulated in such a way that they make it possible to account validly for the relationship between the “Use of assessment technique” and “Performance”. The formulation of hypotheses was made to satisfy the criteria of plausibility, verifiability, precision, generalization, and communicability[2].

Practical and Theoretical Uses

Six primary uses of a practical nature have been identified. They are the uses in “Organizational Development”, “Leadership,” “Coaching,” “Recruitment,” “Clinical,” and “Entertaining.”

Three uses of a theoretical nature have been identified: “Self and Social Awareness,” “Learning,” and “Language”. Of a more abstract nature, these three uses are present transversally in the six practical uses.

Use in Organizational Development

Among the various uses of assessment techniques, those at an organizational level appear to be the most significant and impactful. New information for analyzing teams, departments, companies, and their management during mergers, acquisitions, and reorganizations that is accurate helps make important decisions on people and their organization, which typically need to happen fast and will have important repercussions on future development, engagement, and performance.

Envisioning the jobs to be filled with more accuracy, at all levels of a company, including for its executives and directors, is strategic for what the organization is in need of and how it will later function. The characteristics of individuals who will be recruited and managed in those jobs will need to be consistent and align with the vision and strategic intent. This naturally happens with characteristics such as experience or diplomas. It happens similarly with other characteristics that can be predictive of and help in leveraging performance.

In behavioral terms, with GRI for comparisons with individuals’ adaptive profiles, we refer to those characteristics at a job level as a PBI (Position Behavior Indicator), or at a team or company level as a TBI (Team Behavior Indicator). The use of those indicators has proven to be valuable for guiding recruitment and organizational development by executives and managers.

As a general rule, a better understanding of individual variables is necessary to analyze group phenomena and find effective creative solutions, as research in Agent-Based Models (ABMs) highlights[3].

Given the importance of the relationships between macro and micro phenomena[4] and the capacity of assessment techniques to bring more objective quality information about people at these two levels, one can suppose that the use for organizational development has a strong and positive impact on performance. These observations make it possible to construct the following Hypothesis 1.

Hypothesis 1: The agreement between the use of the assessment technique and performance is more likely if the technique is used in organizational development.

Use in Leadership Development

The following uses of the assessment technique fall into this category: employee motivation and engagement, day-to-day communication, management (technical and people), goal setting, feedback, periodic review, employee onboarding, management meetings, exit management, and employees’ personal development. Although some aspects may be handled by HR and team members, the responsibility falls to the leader or manager of the organization, regardless of its size. For leaders of leaders, the use of leadership applies, to a minimum, to close team members. The ability to deal with conflicts and to manage organizational change are important parts of this category.

The analysis of the effects and use of assessment techniques clearly sets apart the uses in leadership from those that have traditionally been delegated to human resources and organizational development specialists. The effects on leaders when using the information on their own and the effects for the organization differentiate this category from those of recruitment and organizational development.

Research by Kouzes and Posner on leadership clearly demonstrates the need for people and social skills in a leadership role, regardless of their style. A leader first needs social awareness and to find their strength before going out to take on some challenges; Among other things, they need to inspire a shared vision, enable others to act, and encourage the heart[5], which all call for people skills that better quality assessment techniques can assist with.

The importance of a leader’s personal characteristics and style: democratic, autocratic, participative, charismatic, etc., that of the people they lead, and the characteristics of the environment in which they operate have been covered by numerous studies on leadership and management[6]. How relevant those characteristics are depends on the situation[7] and thus the capacity to analyze the fit between the two, and for a leader to know how to adapt[8]. More precise information from assessment techniques offers new insights and augments the capacity of a leader to build the leadership of their team members, and in return helps team members' leadership to build that of their leader[9].

Other research provides evidence that a leader’s most complicated challenges are adaptive challenges that require people to adapt their behavior and change their values, beliefs, priorities, and loyalties[10]. Those, again, should benefit from more objective and accurate information on people’s development.

All the above elements suggest that the link between the use of an assessment technique on leadership is fundamental and has a positive effect on performance. These observations make it possible to construct the following Hypothesis 2.

Hypothesis 2: The agreement between the use of the assessment technique and the performance is more likely if the technique is used in leadership.

Use in Recruitment

“Recruitment” includes the process of selection, sourcing, search, interview, skills assessment, management of high potentials, succession planning, career development, promotion. In large organizations, these aspects are handled by human resources departments. They are shared with leadership and managers with whom they work closely. In smaller organizations, management is more involved, especially when the HR department is only focused on payroll and compliance. Unlike leadership, those aspects can all be outsourced and are increasingly augmented by AI agents.

Assessment techniques have long been used for mass recruitment since the beginning of the 20th century, for executive search since the 1980s, and similarly for promotions in large organizations. The use of mass recruitment is the one that has been most studied in research, asking for compliance with EEOC and ADA requirements, work-relatedness, minimum reliability, and validity. When these conditions are verified, the assessment technique provides incremental value to the other success factors to contribute to individual and organizational performance.

Additionally, while interviewing and making selection decisions, the information from the assessment technique can be combined by the interviewer with other information that is subjective, and is outside the scope of HR processes and AI automation.

As we have observed at GRI, the result of the assessment technique is used at the recruitment stage to quickly help adapt the job to people, or the opposite, help adapt people to the job. The information quality, its relatedness to the job, and the person’s behavior adaptability, are all critical elements for making this decision. The above observations make it possible to construct the following Hypothesis 3.

Hypothesis 3: The agreement between the use of the assessment technique and the performance is more likely if the assessment technique is used in recruitment.

Use in Coaching

Coaching has been on the rise since the late 1990s and has used assessment techniques early on, the most notorious one being the Myers-Briggs Typology Indicator or MBTI. Although the first phase of our research didn’t include this category in teh early 2000s, the evident use of assessment techniques in coaching and mentoring at all levels of an organization made them a natural candidate for the current revised framework.

Assessment techniques used by coaches are numerous[11], more recent than those in recruitment, but focused on individual personal development, team building, and other specific interventions such as conflict resolutions that are a natural continuation of a coaching service. Coaching is delivered typically remotely following a positive psychology or solution-focused format[12]. Techniques generally used by coaches include 360-degree feedback and personality assessments that are typologies (ie, Extroversion or Introversion), which characteristics differ from trait assessments used in recruitment. GRI’s factor approach is a distinct third category that we’ve also seen successfully used by coaches for their clients’ self-efficacy.

Coaching, however, is rarely involved with recruitment, which may be at the root of some challenges coaches are dealing with. It remains distinct from leadership development, as it focuses on personal development at work and in life rather than the organization being led and its outcome. Mentoring, which, rather than guiding leaders, provides them with experience, advice, and wisdom[13], may use techniques, but more rarely so.

The primary impact of coaching and mentoring, as far as the use of assessment techniques may help, is the enhancement of self-efficacy, with self and social awareness—another independent variable of the present framework—happening concomitantly. Studies have consistently evidenced moderately positive effects on individual-level outcomes and personal efficacy[14]. Although not being the focus, the repercussions of increased self-efficacy may subsequently impact an organization’s performance. For this reason, the following Hypothesis 4 was constructed:

Hypothesis 4: The agreement between the use of the assessment technique and the performance is more likely if the technique is used in coaching.

Use in Clinical Settings

Behavioral, mental health, occupational health, work-related stress, stress management, anxiety, depression, emotional exhaustion, burnout, physical health, and well-being services provided to employees, commonly referred to as the Employee Assistance Programs (EAP), are increasingly a standard part of corporate offerings to employees. Assessment techniques were devised and used for clinical practice in the late 1890s. They have been greatly refined over the years and continue to be used by clinicians to diagnose and provide therapy and counselling.

Use of health services has dramatically increased in companies since the pandemic, with new digital capabilities provided by mobile phones, video conferencing platforms, and, more recently, the assistance of AI agents. The services may sometimes extend to development and coaching on a variety of topics, but remain distinct from coaching, with their traditional focus on clinical therapy and counseling. Those services have repeatedly proved to be effective in helping cure mental health issues, consequently improve work effectiveness[15], and lessen a major inefficiency and expense of the modern economy[16].

We’ve observed at GRI psychiatrists and clinicians progressively using different assessment techniques than traditional ones, such as the Myers-Briggs Typology Indicator (MBTI) or the Enneagram. Those assessments have allowed them to get insights about their patients that were not available from traditional techniques, and were useful for diagnosing individual challenges, work-related issues, and counseling solutions. More nuanced information from assessment techniques, whether provided and used within or outside the organization by EAPs, should assist in improving mental health, removing systemic factors originating from the workplace, enhancing a person’s self-awareness, efficacy, and consequently the organization’s performance. These observations make it possible to construct the following Hypothesis 5:

Hypothesis 5: The agreement between the use of the assessment technique and the performance is more likely if the technique is used in clinical settings.

Use in Entertaining

Assessment techniques literally measure any concept one may want to assess. They provide results, which, regardless of their quality, may impress many. They give the impression of carrying some truth, as numbers and statistics by the publisher show, regardless of the seriousness of those statistics. Does one like to know the kind of hero or genius they are? An application will provide the answer in no time. With AI, one can now quickly devise, test, and deploy new techniques.

The current revised framework includes three parallel assessment techniques: 1) Personal techniques, those of everyone, that are subjective and that statistics can never check; 2) Common techniques that companies may refer to for analyzing culture fit, and 3) Esoteric techniques that are as old as the beginning of time. Those assessments are all commonly used in organizations and compete with other assessment techniques.

Assessment techniques at large continue to attract curiosity: what may this other technique tell about me? Participants may ask. They are still popular in magazines, including astrology, although the Internet has helped take the experience online with more interactivity, color, and faster results. They help to entertain discussions, and as such are used as a medium, of which the coach or consultant using the technique is part, regardless of the validity, reliability, or seriousness of the technique. In a large group presentation, answering an assessment technique helps jumpstart conversations and raises the interest of participants.

Although no statistics about the entertaining effect and its relationship to performance are available, the impact on the assessment techniques’ uses and users can easily be observed. It is distinct from other uses and needs to be considered. These observations make it possible to construct the following Hypothesis 6:

Hypothesis 6: The agreement between the use of the assessment technique and the performance is more likely if the technique has an entertaining effect.

Use in Self and Social Awareness

Assessment techniques are used in feedback sessions or with reports to provide participants with information they can use for their personal development. The information helps them understand their potential strengths, communication style, decision-making, career development, and more. Techniques greatly vary in the way the measures are taken, presented, and used. Their quality varies. In any case, they serve as indicators for self-awareness. Further, the information is applied to others to more effectively and objectively know them. To various degrees, this understanding connects the individual information to their function in their team and company. They help be positive about one’s capacity and others’ to perform in their own distinct way.

Discussions about knowledge of Self and Others are central in the field of social sciences. Philosophy, psychology, sociology, anthropology, and ethnology naturally have their say on the question. Self-awareness is central to the personal development and self-discovery market, an estimated $48 billion market in 2024.

Information from assessment techniques can potentially provide guidance for future growth, evidence adaptive challenges, and conditions for improving engagement. They can also provide the means to resolve those issues, avoid and not repeat them in the future. Consequently, the use of self and social awareness helps the implementation of the assessment technique in a large scope of practical applications at an individual and group level, while increasing the impact on performance. These observations make it possible to construct the following Hypothesis 7:

Hypothesis 7: The agreement between the use of the assessment technique and the performance is more likely if the technique improves self and social awareness.

Use in Learning

The process of learning differs between assessment techniques. Online publishers require no training or certification from anyone. The learning and accreditation responsibility falls on their clients. Online resources are abundant. Publishers of assessments used in coaching require consultants and coaches to be certified; Clinical assessments’ publishers will only sell to accredited clinical psychologists. Private techniques obviously require no training, as they are techniques we have been trained in since birth. Common techniques are learned effortlessly through onboarding and by leaving the company’s culture. As for esoteric techniques, the market is filled with books and opportunities to refine one’s learning about them.

The learning, either light or deep, is the starting point for using the assessment technique. The type, depth, and number of applications being learned and used depend on the “Assessment technique” capabilities, the “Publisher” business model, and the “Environment” of the organisation, which more or less supports the learning and use. In the present framework, the four have been analyzed as antecedent variables.

At GRI, we experienced that the training was a critical element for using the adaptive profiles consistently in their different applications, including for leadership and organizational development; unlike in other models, the new assessment technique competes with the leaders’ private techniques. For learning to happen, it requires not only relevance to their ongoing agenda but also real examples, interest in people, impeccable process and logic of the learning, and a little time.

In many instances, one-on-one coaching and mentoring have replaced leadership training delivered in groups. However, interactions between managers during training group (T-group) sessions have proven their value in knowledge acquisition. These sessions have used simple assessment techniques based on typology, as coaching does today. Research conducted on sensitivity training[17] has long evidenced the positive impact of training courses delivered to leaders. Adequately built, the assessment technique brings value for leadership training and becomes foundational.

Learning skills with a new assessment technique occurs over time through practice, much like how it happens in cooking, sports, or playing a new musical instrument. The learning is not an overnight process. The use of new skills is reinforced through their use, sharing with others, and enriching them in the operational field. The capability of continuously building one's skills on the assessment increases the effectiveness of its deployment in practical uses and its impact on the organization’s performance. These observations make it possible to construct the following Hypothesis 8:

Hypothesis 8: The agreement between the use of the assessment technique and the performance is more likely if its learning is nuanced and deep, rather than superficial, and continues over time.

Use in Language

Among the characteristics of assessment techniques, the language and signs created by the technique stand out as incommensurable, as the reading from the literature suggests[18].

Mead’s work[19] gives great importance to signs for the construction of a person and their relationship with the system. Moreover, the functional aspect of signs has not been better analyzed than by Pierce’s work[20] which focused on the symbol itself and its place in the inference process. Viewed from this angle, the assessment techniques’ results can be effective for quickly learning, memorizing, recalling, and building new inferences and skills with other variables on the spot.

The results produced by the assessment techniques have different qualities, including reports with short and long narratives, traits with numbers and scatter charts, typologies with words or letters like ESTJ for the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator, or D, I, S, C for the DISC system. With GRI, we opted for profiles that could concentrate meaning about people’s behaviors in the workplace, based on four factors. Four factors are sufficient to represent up to 90% of people’s behavior.

Once learned, the symbolic language produced by the assessment technique is used to leverage knowledge, communication, and decision-making for the individual and the organization. The more condensed, nuanced, precise, memorable, and shareable the results are, the more they reduce communication’s ambiguity, improve decision-making, and participate in improving other practical uses and their impact on performance. These observations make it possible to construct the following Hypothesis 9:

Hypothesis 9: The agreement between the use of the assessment technique and the performance is more likely if the results and language created facilitate their practical use.

Causes of Use

The analysis of the causal factors made it possible to specify the antecedent variables influencing the use of assessment techniques: the properties of the “Assessment technique”, the qualities, role and interests of “Individuals” using the technique, the organization, its culture and the social “Environment” where the assessment technique is used, and the business model of the “Publisher and consultant.”

The properties of the assessment technique and the business model of the publisher are critical elements that influence and precede their use. There is no measurement of any concept and production of results for any use without the technique itself. The business model of the publisher and consultant influences the autonomy, quality, and resources that enable the deployment. Assessment techniques possess different qualities that limit or enable their use.

Not everyone is interested and willing to accept that a new assessment technique challenges their private techniques or other techniques they already use. Every person and every organization has their beliefs on human nature, about how people and their organizations do what they do, and why. They may change if asked by their company or when challenged by practical outcomes. Adaptive profiles of individuals and organizations can tell how an assessment technique will deploy with more or less process, consensus, communication, and at different speeds. Characteristics of the environment and people progress as the deployment of the assessment technique makes its way in the organization. These observations make it possible to construct the following Hypothesis 10:

Hypothesis 10: The practical and theoretical use of the assessment technique is all the more probable if the assessment technique, publisher, environment, and individual user have appropriate characteristics.

Notes

- ↑ Zaltman, G, Pinson, C., Angelmar, R. (1973). Metatheory and Consumer Research, New York, Holt, Rinehart and Wintson.

- ↑ Mace G, Pétry F. (2000). Guide d’élaboration d’un projet de recherche en science sociales. DeBoeck Université.

The criteria of plausibility, verifiability, precision, generalization, and communicability are discussed in a separate note here. - ↑ Macy M. W., Willer R. (2002). From Factors to Actors: Computational Sociology and Agent-Based Modeling. Annual Review of Sociology, 28, 143-166.

Axtell, Robert L., and J. Doyne Farmer. 2025. "Agent-Based Modeling in Economics and Finance: Past, Present, and Future." Journal of Economic Literature 63 (1): 197–287. DOI: 10.1257/jel.20221319 - ↑ Alexander J. C., Giesen B., Münch R., Smelser N. (1987). The Micro-macro link. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- ↑ Kouzes, J. M., & Posner, B. Z. (2023). The leadership challenge: How to make extraordinary things happen in organizations (7th ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

- ↑ See for instance: Bass B. M. (1990). Bass and Stogdill’s Handbook of Leadership: theory, research, and managerial application. New York: Free Press.

- ↑ Hersey, P., Blanchard, K. H., Jhonson, D. E. (1996). Management of organizational behavior. Utilizing human resources. Prentice Hall. 6th Edition. First published in 1969.

- ↑ Vroom, V. H., Jago A. G. (2007). The Role of the Situation in Leadership. American Psychologist. Vol. 62, No. 1, p. 17-24.

- ↑ Ibid, Bass B. M. (1990).

- ↑ Heifetz, R. A., Linsky, M., & Grashow, A. (2009). The practice of adaptive leadership: Tools and tactics for changing your organization and the world. Harvard Business Review Press.

- ↑ Möeller, H., and Kotte, S. (2022). “Assessment in coaching” in International handbook of evidence-based coaching: theory, research and practice. eds. S. Greif, H. Möller, W. Scholl, J. Passmore, and F. Müller (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 55–64.

Passmore, J. (Ed.). (2012). Psychometrics in coaching: Using psychological and psychometric tools for development (2nd ed.). Kogan Page. - ↑ Sutton, J. (2020) Coaching styles explained: 4 different approaches. Psychology.com. https://positivepsychology.com/coaching-styles/

- ↑ Passmore, J., & Tee, D. (2021). Coaching researched: A coaching psychology reader. John Wiley & Sons.

- ↑ Theeboom, T., Beersma, B., and van Vianen, A. E. (2014). Does coaching work? A meta-analysis on the effects of coaching on individual level outcomes in an organizational context. J. Posit. Psychol. 9, 1–18. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2013.837499

Cannon-Bowers, J. A., Bowers, C., Carlson, M., Doherty, P., Evans, S., & Hall, G. (2023). Workplace coaching: A meta-analysis and recommendations for advancing the science of coaching. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, Article 1204166. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1204166 - ↑ Lyra (2025). State of Workforce Mental Health Report. A report from Mental Health Innovation Summit 2025. https://www.lyrahealth.com/resources/report/2025-state-of-workforce-mental-health-report/

Kuang, T., Guo, C., Ren, M., Fu, L., Li, C., Ma, S., & Li, R. (2025). The effectiveness of e-mental health interventions on stress, anxiety, and depression symptoms in healthcare professionals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health, 25(1), 1083. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-024-02565-6 - ↑ World Health Organization. (2024, September 2). Mental health at work. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-at-work

- ↑ Ibid, Bass B. M. (1990)

- ↑ Carnap, R. (1988). Meaning and Necessity. A study of Semantics and Modal Logic. The University of Chicago Press. 2nd Edition. First published in 1947.

Quine, W. V. (1960). Word and Object. The MIT Press.

Eco, U. (1979). A theory of Semiotics. Indiana University Press. Bloomington.

Eco, U. (1988). Le Signe. Histoire et analyse d'un concept. Editions Labor. Translate from: Segno, 1973.

Eco, U. (1995). The Search for the Perfect Language. Blackwell Publishers.

Hacking, I. (2001). Probability and Inductive Logic. Cambridge University Press.

Hacking, I. (2001). Why Language Matter To Philosophy? Cambridge University Press. 13th publication. First published in 1975.

Korzybski, A. (1933). Science and Sanity. Institute of General Semantics.

Hayakawa, S. I. (1939). Language in thought and action. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. - ↑ Mead G. H. (1934). Mind, Self and Society from the standpoint of a behaviorist. University of Chicago Press.

- ↑ Peirce, C. S. (1935) Philosophical Writings of Peirce. Selection of papers between 1931 and 1935 by J. S. Buchler New York, Dover Publications.