Language and Signs: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

m (→Introduction) |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

As the study of assessment techniques progressed over the past decades, it has become clearer that their effectiveness depends heavily on the quality of their metrics — not just the value of the measures themselves, but also how concisely and accurately they represent the object they measure. | As the study of assessment techniques progressed over the past decades, it has become clearer that their effectiveness depends heavily on the quality of their metrics — not just the value of the measures themselves, but also how concisely and accurately they represent the object they measure. | ||

The measures produced by assessment techniques can be analyzed as signs with the syntactic, semantic, or pragmatic approaches that have long been employed in other fields such as mathematics and physics. The quality of signs significantly influences how they can be learned, retained, and used alongside other information. The representation can either restrict or limit the use of the measures, or, alternatively, add value and facilitate their use. Their validity and utility depend on it. | The measures produced by assessment techniques can be analyzed as signs with the syntactic, semantic, or pragmatic approaches that have long been employed in other fields such as mathematics and physics. The quality of the signs significantly influences how they can be learned, retained, and used alongside other information. The representation can either restrict or limit the use of the measures, or, alternatively, add value and facilitate their use. Their validity and utility depend on it. | ||

In both syntactic and semantic approaches, signs are combined into sequences according to specific rules. The sign is examined based on what it represents, independent of its physical form (the signifier) and the meaning or idea it conveys (the signified). But syntactic and semantic analysis primarily applies to linguistic expressions such as words, phrases, and sentences. The scope of semiotics, the science of signs, is broader than language alone. Analyzed from a pragmatic standpoint, signs from assessment techniques involve guiding principles, beliefs, and the strength of inferences, which are essential to understanding decision-making and communication. | In both syntactic and semantic approaches, signs are combined into sequences according to specific rules. The sign is examined based on what it represents, independent of its physical form (the signifier) and the meaning or idea it conveys (the signified). But syntactic and semantic analysis primarily applies to linguistic expressions such as words, phrases, and sentences. The scope of semiotics, the science of signs, is broader than language alone. Analyzed from a pragmatic standpoint, signs from assessment techniques involve guiding principles, beliefs, and the strength of inferences, which are essential to understanding decision-making and communication. | ||

Revision as of 04:47, 12 November 2025

Introduction

As the study of assessment techniques progressed over the past decades, it has become clearer that their effectiveness depends heavily on the quality of their metrics — not just the value of the measures themselves, but also how concisely and accurately they represent the object they measure.

The measures produced by assessment techniques can be analyzed as signs with the syntactic, semantic, or pragmatic approaches that have long been employed in other fields such as mathematics and physics. The quality of the signs significantly influences how they can be learned, retained, and used alongside other information. The representation can either restrict or limit the use of the measures, or, alternatively, add value and facilitate their use. Their validity and utility depend on it.

In both syntactic and semantic approaches, signs are combined into sequences according to specific rules. The sign is examined based on what it represents, independent of its physical form (the signifier) and the meaning or idea it conveys (the signified). But syntactic and semantic analysis primarily applies to linguistic expressions such as words, phrases, and sentences. The scope of semiotics, the science of signs, is broader than language alone. Analyzed from a pragmatic standpoint, signs from assessment techniques involve guiding principles, beliefs, and the strength of inferences, which are essential to understanding decision-making and communication.

After a brief introduction to the signs, this article discusses the representations typically produced by assessment techniques and how looking at them as signs can reveal, before focusing on how meaning builds on adaptive profiles.

Generalities about Signs

Basically, everything that we can perceive and think about is a sign. A sign can be a musical note, the signs “+” or “$”, “50°F” to indicate temperature, a publicly displayed placard to advertise, any word, or text. The definition of sign: “an object, quality, or event whose presence or occurrence indicates the probable presence or occurrence of something else” can only be broad.

Signs have three fundamental components: how they show, what they indicate, and the rules they imply. For instance, for temperature, its measure is represented by a number on a continuous scale followed by a unit (degrees Celsius or Fahrenheit), such as 50°F. This representation indicates how extremely, very, or moderately cold or hot the temperature may be. Depending on the situation, we can infer how to dress, turn the room's temperature knob up or down, or, if it's our own, take medication if it's too high.

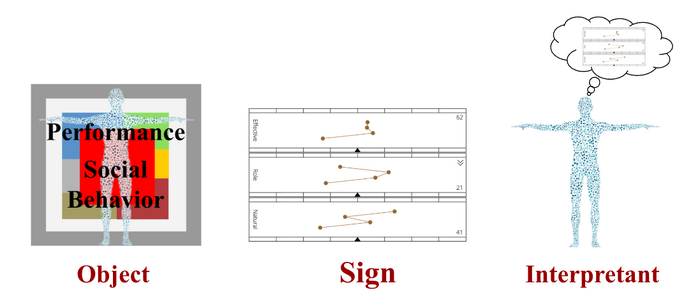

Although the number and quality of variables related to people in organizations are greater and more complex, the principles are the same as for temperature. For individual characteristics, measures appear in many different ways, pointing to very different outcomes, and leading to many different uses. With the adaptive profiles as signs, the object is individual performance and social behavior, and the interpretants are the organization’s stakeholders.

Users of the adaptive profile make use of their visual and linguistic aspects to combine them with other characteristics. Once trained, the profiles help with decision-making, skill development, interaction, and implementation in various managerial, recruitment, and organizational situations. This process illustrates what semiotics refers to as semiosis — the process of creating meaning with signs.

Quality of Signs

Results from assessment techniques can take many forms, such as histograms, diagrams, and spider charts. Some techniques produce written reports of one or more pages. Others produce notations on traits and factors, with labels and values. Still others produce four-letter codes, such as ISTJ or ENFP, as with the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI). In all cases, the tangible element of the sign — what it is — is its first component. The visual aspect of the measure as a sign, how it integrates with other characteristics and techniques, predisposes or restricts its use. The quality of what is measured is one thing; the representation of the measure is another. The two combined tell how the measure can be learned, used, and by whom. It also informs about the inherent limitations and restrictions of the results, what can be done with them, and who their potential users can be.

Indicating Facts and Action

The second element of signs is what they indicate: something, a fact, an event, or an action. In the case of GRI, the adaptive profile indicates social behavior—not skills, values, abilities, intelligence, experience, or interests—but the core aspect of personality that informs how people act, think, and feel. Not living in a vacuum, it also tells how individuals adapt and engage in their environment. Other systems indicate a trait, a type, or another individual characteristic, along with the limitations inherent in what the sign points to.

Assessment measures can be categorized based on whether they reflect qualities or actions. This distinction is crucial for understanding organizations where action plays a key role in social interactions, group dynamics, and value creation. Measures can refer to a quality, such as a skill in computer science. Others can directly indicate how people behave and perform. This makes them different because they can represent both individual and collective actions. In this case, there is no causal link between the sign and the action; the sign represents the action along with its associated effects. If we compare a sign of action to a territory, the territory to which the signs refer is the dynamic action itself and not a territory of qualities. The use of signs as indicators of action allows one to emphasize the action itself rather than the historical reasons and other cognitive, physiological, or social causes that may have led to it. The sign itself can be used to describe individual and social realities from a social-behavioral standpoint. As discussed earlier, the sign's quality will determine the action taken. For example, with GRI’s adaptive profile, the representation includes information on adaptation and engagement, suggesting additional steps the interpreter should take to enhance performance. It also indicates how to achieve this for the person whose sign or measure it is.

Rules Taken by Signs

The third component of signs is the rules, logic, and experiences gained with them. Those rules stem from the sign's indication (Second element) and its quality (First element).

In the context of people and their organizations, the rules built on signs correspond to what should be done in a "particular situation" due to a "specific characteristic" resulting from a "certain technique". These rules refer to options that are possible or to be avoided and are generally communicated by the technique’s publisher. They are generally contained in manuals or presented by facilitators during training. They correspond to the theoretical model underlying the assessment technique.

Manuals' content varies, also constrained by the quality of the sign. Some manuals explain how the assessment was built and provide statistics, but are not explicit about practical aspects of its use, such as how to use the results in recruitment or organizational development. Other manuals are more explicit about their use, but say little or nothing about the metric’s construction and its statistics. Still other techniques provide minimal information or none and simply defer to the theory on which they are built, with sometimes no real connection between the two, or only to the users' implicit theories, as when the measures boil down to labels and their values.

In the case of GRI, the adaptive profile provides information on how characteristics other than social behavior develop and are expressed. Some social behaviors are more desirable in certain jobs than others; lack of engagement (as measured and indicated) consumes energy. All these rules, and many others, stem from observations accumulated over years of using the adaptive profiles.

New signs indicating social behavior provide opportunities to learn and apply new rules. The process varies when the signs and their meanings already exist in the organization and the minds of those who work for it. Learning new rules on social behavior associated with new signs such as the adaptive profiles, doesn’t happen by reading textbooks but through training, interaction, and facilitation. It requires practice, in real, individual cases involving people participants know. This is how they start to bring meaning to the signs.

The same learning patterns can be seen in signs from other techniques, although with limitations inherent to the quality of those signs, which, as noted above, restrict their use to what is already known about those concepts, or to a few expert users and narrow applications. Signs Used by Assessment Techniques

Bar Graph

Bar graphs typically display the measures of behavioral traits and other concepts side by side. For instance, the Limra system calculates 14 traits, regroups them into three categories, and displays a bar graph for each trait. This representation cannot account for the overlap among traits. Decile scales, which are typically used to measure traits, compared to standard deviation scales, distort the representation of trait intensity, thereby affecting comparisons among traits, leading to misinterpretation. Additionally, the representation cannot account for the (emotional) effort required to adapt the trait. The reading of the measures and bar graphs may thus mislead analysis, judgment, and decision-making.

Typology

Typologies represent social behavior in categories. For instance, the Myers-Briggs Typology Indicator (MBTI) produces a four-letter code, such as ISTJ or ENFP. The four letters can only convey the combination of four types, each with its own limitations. As evidenced by the adaptive profiles, behaviors have intensity and can be represented with more nuances when understood along continuums, something the four-letter code cannot do by construction. The combination of the MBTI's four letters yields a maximum of 16 types, within which people's behaviors could be located. Social behavior is both relatively stable over time and adaptable to some degree. Those aspects cannot be rendered with the four letters and any typology. Thus, it limits their applications for understanding people to those three aspects: relative stability, adaptability, and behavioral intensity. The condensed nature of the four letters, however, eases their learning, understanding, and use, even if the measurement quality is limited and misleading.

Typologies are commonly used for coaching and team building; they are easy to understand and represent, but their representations limit their use to these applications. Their general validity and utility for any other applications are low.

Multiple-Typologies

With multiple typologies, several types — also called themes by some techniques — of a participant are ranked by order of intensity. For instance, CliftonStrength measures 34 themes, regrouped into four domains, and lists the five most intense themes. Those representations, by construction, present challenges similar to those of typologies, as they don’t evidence the intensity of each dimension with nuances along continuums. As noted above for typologies, social behavior is both relatively stable over time and adaptable to some degree, and these aspects cannot be captured by multiple typologies, thereby limiting their applicability. The condensed nature of the top themes, however, eases their learning, understanding, and use, even though their measurement quality can be misleading.

Spider Chart

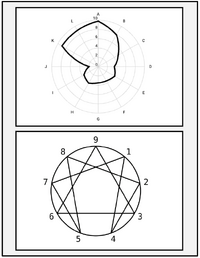

The layouts, in the form of spider or radar charts that use a central point from which multiple axes (spokes) radiate, each representing a different characteristic, limit the measures to two sides, usually with the null value on one side and 9 or 10 values on the other.

The measures’ limitations are the same as for bar graphs, although the representation in a spider chart is different. The figure on the right is one of the Enneagram, whose representation is close to a spider chart: in this representation, the values appear only on the outer circle; the measures’ limitations are closer to those of typologies (see below).

The limitations do not occur when the dimensions are measured with standard deviation scales that extend on either side, without such restrictions. Although measures presented on a spider chart are concentrated, which eases their reading, comparisons between the dimensions are difficult, especially when one dimension is on the other side of the chart, as is the case with the Enneagram.

Label

In producing traits and labels associated with values, the techniques rely on the interpretation that the end-user will produce from them. The technique and publisher’s rules remain distant from those of the user, because, in practice, any user has an idea of, for instance, extroversion, leadership, authority, delegation, etc.. Measures in this way only have the value of potentially questioning the user or reinforcing them regarding the intensity of a construct that they already assign meaning to. When a trait is measured by a technique that is clinical or too abstract, it forces the user to rely on their clinical expert for insights into its meaning.

Report

Reports offer another arrangement of nuances, though less concise than those from diagrams, charts, and histograms. They are subject to the same common-sense limitation described above for labels. The narratives are typically repetitive, hard to memorize. When written solely on the basis of personality assessments, they are all the more suspicious, as they provide generalizations and explanations on dimensions they don't assess. Each sentence is a fragmental interpretation of the dimensions being measured or should be, although the tendency for reports is to make suppositions beyond the capacity of what’s measured. Only repeated observations can reveal whether the narrative statements are valid, which is not possible without knowing which dimension they're coming from. When comparing with the adaptive profiles, statements of reports show as either neutral, imprecise and misleading, or valid, but the three being mixed together.

When an analysis focuses on organizational needs, recruitments, and job fit, rather than purely on the individual, the relationships between the person and the context are hard to analyze and impossible to quantify. That’s a major limitation when using reports for these applications.

Adaptive Profiles

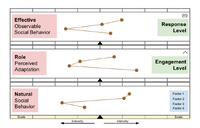

In GRI’s adaptive profile, the signs are reduced into profiles (Natural, Role, Effective), scales (Standard deviation), factors (1, 2, 3, 4), factor interactions (connections between factors), arrows (engagement level), and numbers (response levels) as it is illustrated here.

Building Meaning on Adaptive Profiles

The benefits of an assessment technique when used at a strategic level largely come from the quality of the signs being measured and their capacity to be learned and guide action at that level.

A sign can encapsulate and concentrate meaning, which can then serve as the basis for new, more effective guiding principles to be shared within the organization. Through the symbol, the representations and arguments conveyed can benefit from new experiences, discussions, and refutations, something that private techniques can’t do. Private techniques are everyone's semiotic process, remain subjective, and are not shared. Common and esoteric techniques are open to refutation; that’s probably why they rarely survive the test of time for organizational applications. The adaptive profile as a sign indicates performance and social behavior. The two aspects together help diagnose and provide solutions to improve individual and organizational performance. They require learning the signs and their related new representations, language, and rules — the three components of the sign.

The measures typically provided by assessment techniques relate to concepts that are available and used in common language, validating or refining a user’s concept but without conferring new symbolic or argumentative value.

For instance, the measures of “creativity”, “entrepreneurship”, and “strategic thinking” rely on the definitions the assessment's author gave them. A synthetic definition or an author's booklet may illustrate those constructs. Nevertheless, “creativity”, “entrepreneurship”, and “strategic thinking” have meanings beyond what the technique can assess. They occur in different ways, depending not only on the person being assessed but also on the context. The assessment ultimately leaves the user of the technique with their own private understanding, definitions, and rules, although the technique may point out and disqualify those with very low scores, which may be their only utility.

The same applies to the adjectives and expressions that characterize organizational action: communication, extroversion, initiative, etc.. Without new representations, meaning, and rules that can carry more value for the organization, and without appropriation by their interpreter, the measures rely only on the interpreters’ private understanding and rules.

The logic of signs applies not only to individual characteristics but also to the techniques that measure them — formal, semi-formal, and statistics-based techniques — for understanding their use in organizations. An assessment technique can potentially exist without being used. Its use may cover qualities and rules specific to the organization and vary from person to person. Their sign values help compare them, the characteristics they measure, and what the organization and individual users can do with them to improve performance.