Disruptive vs Normative Behaviors

The indications below aim to give general information on the profiles and behaviors analyzed with a factor-based approach, with two fundamental tendencies: normative behaviors versus disruptive behaviors.

Generalities

Behaviors that characterize how we communicate, socialize, and more generally act can be analyzed through a limited number of factors[1]. This result comes from work initially undertaken by Allport & Allport[2], Thurstone[3], Allport & Odbert[4], and others who researched adjective lexicons and the concept of personality. Factor analysis leads to a relatively small number of transposable factors between cultures for describing behavior.

The four factors measured by GRI, called factors 1, 2, 3, and 4 (see below), can be compared with the findings from Marston[5], Burt[6], and Clarke[7] on the feelings and emotions of normal people. These factors also align with the dimensions identified in sociological studies, such as those of Parsons[8], Parsons & Shils[9], and Katz & Khan[10]. They were evidenced by studies on the five-factor approach conducted by Goldberg[11], Costa & McCrae[12], Saucier, Thalmayer, and Payne[13], and other more recent studies on the optimal number of personality factors[14].

Disruptive Behaviors

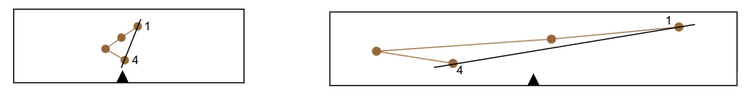

For these disruptive behaviors, the profiles show a high factor 1(to the right), a low factor 4 (to the left) lower than factor 1 (to the left). Cf. Figure 1.

Factor 1 expresses the need to have authority and influence people and events. People with a High factor 1 are confident, independent, innovative, and enterprising. People with a Very High 1 can be perceived as arrogant, ego-centric, or belligerent. A High 1 needs a competitive environment that rewards entrepreneurship and the ability to take on challenges.

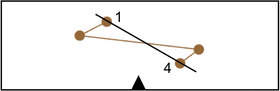

Unlike High 4s (see below), a Low 4 is seen as casual, independent, carefree, or unabashed. A very Low 4 can be seen as rebellious, unruly, disrespectful, and neglectful. Low 4s need little structure and few rules. The wider the profile, the more the disruptive behaviors described above are evidently expressed. Conversely, the narrower the profile, the fewer disruptive behaviors described above are observed (Cf. Figure 2).

Entrepreneurs and change agent leaders have disruptive profiles as they strongly need to leave an imprint on discussions, decisions, and their environment. The authoritarian behaviors of Adler and Adorno are part of this disruptive tendency. They also correspond to those of the β factor of the approach with two theoretical constructs or meta-features of Digman found in numerous studies, including that of Hogan, with the notion of popularity.

Personal innovation or the will to change, along with a high-risk tolerance, are characteristics of these profiles. By being spontaneously inclined to take risks, these people also engage more spontaneously in innovative, disruptive behaviors, such as technological innovations.

These behaviors also correspond to personal efficacy in situations of change, in environments where it is necessary to resist in order to accept negative feedback, or in situations where it is necessary to show persistence in order to perform over time in the face of adversity or to demonstrate stronger-than-average performance. Disruptive behavior is partially located in the Extraversion and Neuroticism dimensions and inversely in the Agreeable and Conscientious dimensions of the five-factor approach, without an exact correspondence, particularly regarding the clinical aspects of the dimensions, which are out of focus for GRI.

Normative behaviors

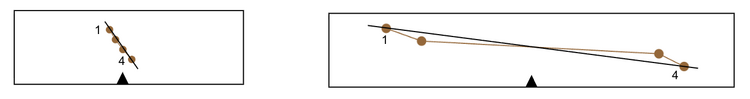

For these normative behaviors, factor 4 is high (to the right of the profile), and factor 1 is low (to the left of the profile) and higher than factor 1 (to the right of factor 1). See Figure 3 below.

A high 4 expresses the propensity to conform to rules and structures, the opposite of being informal and uninhibited when factor 4 is low. This factor accentuates the need for details. A High 4 needs rules. A very High factor 4 can be perceived as inflexible and anxious to do everything perfectly.

Unlike High 1s, Low 1s are modest, devoted, and even discreet. When factor 1 is very low, the person can be seen as docile and withdrawn. A Low 1 prefers to work with a team and in an environment free of conflicts. The wider this profile, the more normative behaviors are intensely expressed. Conversely, the narrower the profile, the more the normative behaviors are difficult to evidence. See figure 4 below.

The characteristics of the normative profile are close to those described in the literature for the conscientiousness dimension of the five-factor approach. People with these profiles are disciplined, organized, task-oriented, and rule-bound. This dimension has shown links with performance in structured environments where ambiguity, uncertainty, and rapid adaptation to change are absent.

We also find the Agreeableness dimension of the five-factor approach in this normative profile. According to this dimension, people are kind, cooperative, generous, and courteous. They are loyal. Positive relationships between performance have been demonstrated with the two factors, Conscientiousness and Agreeableness, in positions requiring frequent interaction and cooperation. The Agreeableness dimension of the five-factor approach showed a strong link with the propensity to be positive, to be engaged in conversations other than those relating to work, and to provide empathetic support to others on an emotional level. These conversations tend to reinforce the personal values of others.

This normative profile matches the descriptions of the α dimension described by Digman, as opposed to the β dimension of the above disruptive profile. The α dimension suggests a strong social desirability to say socially acceptable things about oneself and others. The normative profile portrays socially acceptable behaviors. Unlike hostility, an undesirable social trait, kindness, conscientiousness, containing impulses, and containing aggressiveness have always been subject to rules of social conduct.

Notes

- ↑ Saucier, G. (2003). An Alternative Multi-language Structure for Personality Attributes. European Journal of Personality. Vol. 17, p. 179-205.

- ↑ Allport F. H., Allport G. W. (1921). Personality Traits: their classification and measurement. The Journal of Abnormal Psychology and Social Psychology. Vol 16., p 7-40.

- ↑ Thurstone L. L. (1934). The Vectors of Mind. Psychological Review, Vol. 41, p. 1-32.

Thurstone L. L. (1959). The measurement of Values. The University of Chicago Press. - ↑ Allport, G. W., & Odbert, H. S. (1936). Trait names: A psycho-lexical study. Psychological Monographs, 47, 1–171.

- ↑ Marston W. M. (2002. Emotions of Normal People. Routledge. First published in 1928.

- ↑ Burt, C. L. (1950). The factorial study of emotions. In M. L. Reymert, Ed., Feelings and Emotions. New York: McGraw-Hill. Pp. 531-551.

- ↑ Clarke W. V. (1956). Personality Profile of Self-Made Company Presidents. The Journal of Psychology. 41, p. 413-418.

- ↑ Parsons T. (1951). The Social System. New York: The Free Press.

Parsons T. (1964). Social structure and personality. New York: The Free Press. - ↑ Parsons, T., Shils, E. A. (2001). Toward a general theory of action.: theoretical foundations for the social science. New York: The Free Press. First published in 1951.

- ↑ Katz D., Kahn, R. L. (1978). The social psychology of organization. New York: Wiley. Originellement publié en 1966.

- ↑ Goldberg, L. R. (1990). An alternative "description of personality": The Big-Five factor structure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59, 1216-1229.

- ↑ Costa P. T., McCrae R. R. (1992). Four ways five factors are basic. Personality and Individual Differences, Vol. 13, p. 653-665.

- ↑ Saucier, G., Thalmayer A. G., Payne D. L. (2010). A Basic Bivariate Structure of Personality Attributes Evident Across Nine Languages. Unpublished.

- ↑ De Raad, B., Barelds, D. P. H., Timmerman, M. E., de Roover, K., Mlačić, B., Church, A. T. (2014). Towards a Pan-cultural Personality Structure: Input from 11 psychological Studies. European Journal of Personality, 28, 497-510.