Research Methodology

Introduction

The constructivist approach used in this project emphasizes the importance of defining the epistemological position and the researcher’s background. These two aspects are introduced first. This article also covers the procedure and operational steps. A general question is gradually narrowed down to a specific question that can be operationalized. Those two questions are key steps that help build a framework. The project took place in three phases, which are described throughout the document. It resulted in the development of individual and organizational performance metrics that guided the analyses, the construction of the overall framework, and its implementation in organizations. These aspects of performance, which are part of the methodology, are also presented.

Epistemological Position

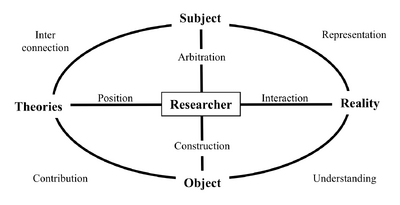

The methodology combines constructivist, positive, and interpretative approaches to grounded theory[1] . It is through field observations, inductively, that the uses of assessment techniques in general have been clarified. It is also from these observations that the variables and indicators of the framework have been developed, continuously combining theoretical elements and integrating them into analyses and processes in a deductive way. This approach was especially important when delving deeper into the concepts and variables used in the framework. The research process led by the researcher, in contact with the field and theories, makes it possible to gradually bring out the general question, the specific question, and beyond, the hypotheses, and the model with its variables and indicators, while seeking a field of validation. The researcher is thus at the intersection of different theoretical and empirical perspectives, of the subject being dealt with, and of the theoretical object being constructed. The research question emerges from the connection between empirical realism and theorization; understanding a phenomenon requires paying attention to all its expressions, meanings, and values. This involves active fieldwork, note-taking, and in-depth reading that directly or indirectly relates to the research question.

In conducting the project, the researcher faces two dualisms. The first dualism stems from the relationship between the research object and the researcher. The second dualism arises from a transactional relationship between the researcher and others in constructing knowledge. The aim of this double dualism is the creation of an emerging theory[2]. The processes linking these different poles to the researcher are illustrated below.

Other paradigms complement this constructivist process[3]: the hypothetico-deductive approach is combined with the empirical approach to develop a model and test it through case studies. From a positive perspective, the requirements of verifiability, confirmability, and refutability must be satisfied[4].

Following the interpretivist perspective, analyzing social situations and assessing individual and group performance have been improved through adaptive profiles. For the test cases, especially those used in Step 1 of the project, the leaders' profiles provided deeper insight into their leadership styles, decision-making, communication, and overall behaviors. The members of the sales and customer service teams were evaluated based on their adaptive profiles. More broadly, adaptive profiles help understand people in context, their lived experiences as they translate into action, and their perceptions of adapting. During interviews, having the interviewees’ adaptive profiles has helped ask more creative questions, refine the analysis, and, in turn, bring new perspectives. As the lead researcher, my own adaptive profile has increased my awareness of potential biases when observing in the field, interviewing people, taking notes, writing, and more broadly by conducting research according to its purpose and possible contributions.

Researcher Perspective

All social science research projects include a subjective dimension from their authors, which I like to acknowledge. But I first want to acknowledge that many, directly and indirectly, have participated in this project over the years, for their contribution through their work in growing, implementing, and testing the framework, whether being professors, doctors, consultants, clients, family, or friends. This work would not have been possible without them. I thus prefer to refer to myself as the lead researcher.

Exploring the World

I started this project when I did my PhD at the same time I was a company’s CEO of a technology startup. After completing my master's degree in mechanical engineering, I spent three years in an international corporation as an industrial engineer in France and then in Japan in a role that later became known in Silicon Valley as a technical evangelist. A six-month gap on my return from Japan for a world tour allowed me and my wife to live enriching experiences on a human level. Travelling the world certainly deepened my interest in humans' positive differences, and later, to envision GRI’s project as cross-cultural.

The company I founded grew rapidly and successfully through two VC rounds, with internal and external growth, for ten years before I sold it to an international group. It was at the helm of this company that I had my first leadership experiences. One of my observations was that leadership issues are both the most important and the most complex for the development of an organization. These issues can quickly become preponderant once the other technical, financial, and marketing aspects have been dealt with. I was directly confronted as a leader with the problems of recruiting salespeople who sell and others who don’t, the merger of teams during an acquisition of a company four times larger thant the original one, and many other human situations that all start-up founders are generally confronted with when growing a company at high speed, or anyone in a leadership position interested in the human aspect of organizations. My estimate of time spent on these aspects is close to Mintzberg's estimate of 85%[5].

I believe I made excellent recruitments and was proud of them. But I also experienced the frustration of the unplanned departure of great employees hunted by executive search to work for competitors, or of development efforts invested without success because of people’s unwillingness to participate in the efforts, execute a planned strategy, or even provide feedback.

The less relevant advice given to me, including from the board of directors or management group I was a member of, was certainly on the human side of the organization. Marketing, production, and other tangibles were easy. Social aspects, not. At the time, it was graphology that was used in addition to intuition, but everything was good to reassure about the quality of candidates and their management. Consulting, soon to become coaching in the 1990s, was useless for assisting in recruitment, but just fixing issues a posteriori, partially, and at high cost.

I had one day the opportunity to address these questions relating to social and human aspects with a colleague who used personality assessments with great satisfaction and was sufficiently receptive to his arguments, and finally convinced to get trained in this system. So I used a personality assessment as a CEO for two years before selling my business and starting a consultancy, being able to devote myself entirely to my new activity.

One of the implications of this experience is that I tried to make the most of spending a large part of my time in the field in contact with executives, human resources managers, other consultants, and in contact with large global companies, as well as small start-up and family businesses. This exploration field was an extremely varied and stimulating source of observation. It has been critical for building the first version of the framework during the thesis in phase 1 of this project, and later, to continue refining and enlarging it.

Because of my background as a company’s founder and CEO, although I socialized with many HRDs and human resources experts, I never felt particularly obliged to follow the generally adopted trend that assessment techniques are made for research, HR practitioners, clinicians, and coaches. The unpredictability of human problems in organizations and the unusual fact that executives may also use assessments, as I did, when this technique was traditionally in the hands of experts or gurus, are at the origin of the focus on leaders in phase 1 for my PhD thesis defended in 2006.

Much work continued after 2006, with the advent of new assessment techniques entering the market, new research findings in academia, an increased use of the Internet, and the acceleration of the coaching practice. I had moved to Silicon Valley in 2005, as part of a family project. With my wife, being a US native, and our four daughters, being Franco-American, we decided that Palo Alto was a better place for continuing their education. Combined with Silicon Valley being a buoyant place helped make the move.

The consequence for the project is that the observation field’s center of gravity changed from Paris to Palo Alto. Although the first large exploration field already included the USA and other countries, the new field would be influenced by the Bay Area’s business culture. The framework was used with a growing number of client organizations. Much that had happened in the assessment field in the Bay Area, events at Stanford, SV Forum, Vistage, Y Combinator, other organizations, and startups boosted by the Internet, provided new insights to strengthen the framework. The period from 2006 to 2011 corresponds to phase 2 of the project.

The creation of GRI (Growth Resources Institute) in 2012 provided new tooling for measuring individual and group performance, and opportunities to advance the project, refine it, test it, and build it as it is today. This event started the project’s phase 3. It’s during this period that the framework was further amended, reflecting new uses evidenced not only in the Bay Area but also in other countries where GRI had a footprint. As anticipated, the learning aspects of the symbolic language from the adaptive profiles had progressively taken more importance. During the pandemic, new technologies, also with the impulse from larger clients, helped improve the online and self-paced learning. This has had an important impact on the capabilities of the GRI’s framework to be deployed and tested at a global scale. The more recent advent of AI creeping into every aspect of assessment techniques urged me to formalize the general framework that had progressed over the years, and communicate about it.

General Question

The unpredictability of human behavior in organizations, the lack of objectivity when discussing these matters, and leaders’ challenges in navigating this subjective landscape are at the origin of the project.

How is it that people's behavior is difficult to predict? Why is an organization’s performance so sensitive to its leadership? How is it that some people have trouble making decisions, communicating, following rules, or taking risks without being able to anticipate these difficulties, and despite costly development programs that do not fix them? Why do some people manage to develop extraordinary talents without it being clearly a matter of intelligence or knowledge? Could the need for change, re-engineering, or high stress in organizations be better addressed earlier?

The practice of leadership often faces people-related challenges, much like a doctor at a patient's bedside. Leaders find themselves addressing unavoidable wounds. They tend to examine social issues more closely when these issues become awkward and begin affecting other areas such as sales, finance, marketing, or production. It seems that one trait of these challenges is how easily they can be concealed until they suddenly erupt and significantly damage the organization’s overall performance. These challenges, which are closely linked to psychological, sociological, and economic aspects, are certainly not new. Throughout history, even before the rise of companies, they have been issues faced by societies trying to protect themselves from internal and external destructive pressures. Organizations evolve alongside the challenges they encounter, guided by human knowledge.

Even though new statistics-based assessment techniques that emerged in the past decades seem to offer better quality results than astrology reports or a crystal ball, why do those more advanced techniques continue to be in the hands of gurus and HR experts whose role consists of printing reports? How might those techniques actually differ? Could they help better anticipate human and leadership challenges in organizations and solve them more effectively than no technique at all? Given the advances in psychology, neuroscience, organizational development — not to mention technology — we might question how progress in these fields has helped improve solutions for addressing leadership and organizational challenges.

In response to this general question, observing the variety of assessment techniques available on the market and noting progress gives hope. These techniques have been traditionally applied in a range of areas, including clinical cases, personal development, recruitment, and coaching. However, the quality of their results and the benefits they provide remain uncertain. The challenges appear to be both upstream, in strategic thinking, and downstream, in everyday execution of the strategy, with traditional techniques often unable to address these challenges directly. These aspects directly involve leaders.

During the first phase of this project, the general question directed attention to the use of personality assessments by leaders. This was taken in the specific question, which was operationalized and tested within the framework. The research demonstrated that factor-based approaches have clear advantages in representing and measuring individual and organizational performance. Leaders' use of these approaches allowed for better monitoring of two key performance components, called strategic and social, which have implications for economic performance. In phases 2 and 3, the above general question has stayed the same. However, in phase 3, it now includes a new measurement of performance with GRI that can be applied across individuals and organizations. Assessment techniques are everywhere in organizations. The most common one is everyone’s private subjective technique. Common techniques, esoteric techniques, and many others often compete with each other. The general question for phase 3 aimed to expand the specific question to include techniques and users, while still keeping the leaders' focus.

Specific Question

The transition from the general question to the specific research question follows the approach proposed by Mace and Pétry. The general question is too broad to serve as the focus of an investigation. During phase 1, it was necessary to rely on exploratory interviews with people from different organizations: executives, human resources managers, and consultants using personality assessments. Then, a new literature review was conducted with two main objectives: to evaluate the current state of knowledge accumulated by researchers on the studied subject in order to identify gaps, understand how the problem was expressed and addressed by other researchers, and propose a better conceptualization of the problem, if necessary. In parallel, the approach appeared to take a qualitative shift; my initial observations were summarized on one of the case studies of the testing field.

This work confirmed the abundance of discussions and controversies in the humanities and leadership involving the use of tools and personality assessments. The contrasts between behavioral and cognitive psychology, sociology and psychology, psychoanalysis and experimental psychology, and among different behavioral approaches, among others, leave many avenues open for exploration and analysis, while providing rich theoretical support. For conducting research projects, the positivist, constructivist, and interpretivist approaches enable scientific progress in both exploratory and confirmatory ways with substantial methodological support.

Field observations showed that leaders were utilizing personality assessments, even though these tools were increasingly adopted by coaches and human resources teams. This is evident even on a superficial level when personality assessment reports get into their hands. Depending on the techniques and business models of publishers, leaders also engage with these techniques through training and profiles rather than narratives and summaries. Based on these premises, the initial specific question was formulated in phase 1: How does the use of personality assessments by leaders impact an organization’s performance?

There have been many studies analyzing the relationship between assessment techniques in mass recruitment and clinical applications. There are also numerous studies on how the introduction of new techniques by managers relates to performance, such as those involving performance measures of various kinds by Kaplan and Norton. Given the gaps identified in the literature, the specific focus of phase 1 was on personality assessments and leadership use, and how their application relates to performance.

During phases 2 and 3, the exploration field continued to grow, including in the San Francisco Bay Area and new countries. The variety of uses, concepts, user types, and publishers of assessment techniques increased. The use of typology-based techniques by coaches and psychologists also grew. More leaders relied on assessment reports and summaries from practitioners or directly from publishers. While leaders’ use remained central to the project, incorporating other applications in coaching, clinical treatment, and entertainment helped highlight the differences among techniques and how their use and users affect performance. With an expanding body of literature on the theoretical foundations and broader access to exploration, the scope of the framework first initiated in phase 1, continued to expand. The main question for the overall framework evolved into:

The new question broadens the initial focus on personality assessment and leaders but still centers on performance. The approach remains guided by a concern for methodological accuracy, mutual enrichment between empirical and practical elements, and adding value to leadership and organizational development sciences. The semiotic aspects, although important to the project, were set aside in the specific question from the start. They had been discussed in several rounds between the formulation of the question and the development of the framework. However, it seemed beneficial to continue emphasizing these aspects through a hypothesis, to avoid making the specific question more complicated or too abstract and difficult to grasp.

Performance

The specific question was intentionally connected from the beginning to an idea of performance, without defining it too precisely, but through a relatively vague concept of an economic and social nature, based on a broad idea of productivity, efficiency, engagement, and being in flow. The notion of performance, even if vague at the start of phase 1, seemed crucial in guiding the project and giving it a nomothetic character, aimed at creating rules and a model leading to an understanding of performance. The concept of performance was gradually clarified throughout phase 1[6].

Performance and non-performance of individuals and social groups are subjective concepts, tied to their values, including social behavior values. The adaptive profiles clarify this point. The performance measures devised at GRI in phase 3 represent individual social behaviors—how people act, think, and feel about their actions—and highlight the eventual mismatch and need for behavioral adaptation as the environment, including leaders, expects individuals to behave. The measures invite leaders to more clearly and realistically envision their expectations in jobs, teams, and organizations using comparable terms to those measured at the individual level.

Ultimately, the adaptive profile’s symbolic representation becomes central to developing performance. The symbol produced by the assessment technique is used in various applications that this project highlights. It extends their use beyond typical recruitment and coaching uses, for strategic applications and day-to-day management. The symbol captures a certain view of performance and non-performance at both individual and group levels. It encompasses behavioral, affective, and cognitive aspects, showing how individuals and groups adapt and interact within the environment.

Based on the preliminary work of phases 1 and 2, GRI’s metrics were developed in phase 3 to improve performance measures and to analyze and more thoroughly compare other techniques, uses, and effects. As for phases 1 and 2, the general framework’s focus on performance makes it possible to channel the field observations on the use of assessment techniques, particularly when interviewing people, by various users, and in different situations.

Framework Building and Testing

The analysis of the use of the assessments, their chronology, their antecedents, their effects, and their role was originally carried out during phase 1 on a large exploration field made up of 500 companies and a little more than 1,100 individuals. By comparing observations with theories, the first framework was built, and the nine hypotheses with their variables and indices were identified.

From there, a procedure for testing the hypotheses through interviews with managers, as well as tools for analyzing groups of people and measuring performance, were developed. Two companies were selected to test the model built, as well as three managers for each of the companies on three hierarchical levels, starting from the general manager. The leaders were all trained in the personality assessment and involved at different levels in various uses of the assessment. The two companies were from different sectors. One was a subsidiary of an international pharmaceutical company, the other was a start-up specializing in customer loyalty products for banks.

The process adopted to form the use categories and the refinements and comparisons carried out on the two test companies made it possible to have a solid, relatively general model, based on well-identified variables and indicators. The model could then be reproduced by the semi-structured interview technique using an interview guide. The conclusions that could be drawn from the model were thus open to criticism and refutable.

When GRI started in 2012, we continued working with this model, refining it, and using it in other cases with other data collected, in a similar way, to validate or not the hypotheses on the use of personality assessment in organizations. We’ve used this model with the GRI and other techniques to contrast their use and their impact on performance.

Procedure and Operating Steps

Phase 1 development can be outlined in four steps spanning from October 2001 to June 2006. Before the project officially started in October 2001, some investigations had already been conducted in France and the United States on assessment techniques, management, and leadership. The psychometric aspects had already been studied.

- The first step spans from October 1, 2001, the start of the academic research, to September 2002. During this time, the general research question was defined. A specific question and an initial research plan were created. Content analysis helped clarify the concepts of assessment, personality, and leadership, and the theories that support the framework. The methodological and epistemological aspects of managing the research project were outlined during this period. A first report was drafted at the end of this initial step.

- During the second step, impasses encountered in the implementation of the specific question led to new questions, required rearrangement of the project, and then going backward in the development process to clarify the specific research question, which ended in being “How does the use of personality assessment by leaders increase the organization performance” Starting with “How”, the project positions the work in a logic of discovery of clues and exploration that is both empirical and theoretical. Due to the lack of research on the social object being studied: “the use of personality assessment by leaders”, an exploratory approach was necessary to describe the processes of use. The hypotheses were then formulated, and a first framework was built. In parallel, the theories related to the specific question began to be clarified. Team analysis tools were developed at this stage. The two case studies had already been negotiated. A second interim report was produced in May 2003, which more specifically presented the concepts of “assessing” and “personality” and initiated research on the process of “use”. Qualitative and quantitative information had already been collected. A first draft of the framework was drawn.

- The third step covers the period June 2003 to October 2004, during which the test of the hypotheses by a quasi-experimental approach on two cases was carried out. The interviews were conducted, transcribed, coded, and analyzed. The model, its variables, and its indicators were clarified, with a more elaborate definition of the concept of performance. A discussion and conclusions were initiated in the drafting of the pre-defense report.

- In the fourth step, the final report was drafted. It included the first criticisms of the project from professors and doctoral students in the research laboratory and corrected the issues raised during the pre-defence in November 2004. The analytic work and measures on organizational performance were more particularly studied during this last step, and taken within an analysis framework of symbols and social action. The editorial work made it possible to make a coherent presentation of the research work results.

Phase 2 covers the period of 2007 to 2011, during which the framework was applied, tested, and refined with new organizations. Observations of techniques, organizations, and users were broadened. The tools devised in step 1 for analyzing jobs and organizations were taken to the Internet.

Phase 3 began in 2012. During this phase, new performance metrics were developed and incorporated into the GRI platform. The platform, soon available in five languages, could then be used for deployment at affiliates and clients, along with training manuals also available in five languages. The survey was quickly translated and validated in 23 languages. A first technical report was published early on and updated over time, notably in 2024, with results on reliability over a 10-year span. Tools were added to the platform for remote learning of the adaptive profiles in 2020, and then self-paced in 2024. The books “Lead Beyond Intuition” and “Discover the Best in You” were released in February 2019, “The Missing Metric” in July 2022, and GRI’s wiki in 2025, all helping to expand the applications and reach of the adaptive profiles. The framework was gradually updated with new uses and users to form its current version.

Notes

- ↑ Glaser, B. G., Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of Grounded Theory: strategies for qualitative research. Aldine de Gruyter.

- ↑ Wacheux, F. (1996). Méthodes Qualitatives de Recherche en Gestion. Economica.

Ibid, Glaser, B. G., Strauss, A. L. (1967) - ↑ Girod-Seville M., Perret V. (1999). Fondements épistémologiques de la recherche. In R. A. Thiétart. Méthodes de recherche en management. pp. 13-33. Dunod.

- ↑ Popper, K. R. (1963). Conjectures and refutations: The growth of scientific knowledge. Harper & Row.

- ↑ Mintzberg H. (1975). Occupation: manager. Myths and realities. Harvard Business Review.

- ↑ See here a study of performance models, and how it led to the conceptualisation of performance used in the project.