Individual Characteristics

Introduction

This article presents the individual characteristics that underpin our assessments, decision-making, relationship-building, and performance characterization. Characteristics are major factors in the differentiation of individuals. Many characteristics are naturally used in forming judgments, but only a few become significant when considering people’s roles and their management in organizations.

The above aspects are discussed, as well as how the characteristics can be classified to improve performance. Individual characteristics are not only about individuals but also shape expectations for the positions people occupy, how decisions will be made, and how communication will occur. Once a position is occupied, individual characteristics define a model for that position.

Characteristics' Assessment

The quality of characteristics is closely linked to the techniques used to assess them. At a minimum, private techniques are the most basic and widespread methods employed by anyone. If not private, techniques may include those used informatively by organizations, esoteric techniques, and other approaches, such as semi-formal, formal, and statistical techniques[1].

The survey technique that uses a questionnaire and statistical analysis helps achieve a more effective and objective measurement of certain characteristics. It is considered objective because the results are obtained without relying on someone else’s judgment. The interpretation or analysis may involve judgment, but not the measurement itself. Most characteristics are straightforward and can be easily assessed through private techniques. However, other characteristics like abilities and social behavior are more complex and harder to define. They benefit from a standardized process, the use of metrics, and the application of statistics, similar to how any other tool enhances human capabilities.

The Big Seven

Individual characteristics are numerous, although some may be regrouped; only a few are generally considered for performance. As noted above, some are easy to define and assess, while others are less so, even though they are critical. The seven characteristics shown here are commonly used in organizations. They help focus attention when assessing someone for a job, especially when several assessors are involved. Social behavior at the center is the most obvious, visible, and present; however, harder to assess objectively. This characteristic has been at the center of GRI's research project phase 1, which aimed to improve and define performance when social behavior measures were used by leaders and managers. The seven characteristics are as follows, with brief definitions. They are then detailed one by one before other characteristics are discussed.

| Characteristic | Brief Description |

|---|---|

| Social Behavior | The way people act, adapt, and perform from a behavioral, emotional, and cognitive standpoint. |

| Intelligence | The general mental ability that accounts for a person’s intellectual agility, memory capacity, and verbal fluency. |

| Values | The beliefs and ideas people have and value the most. |

| Abilities | The specific mental and physical aptitudes to perform, which may partially be innate. |

| Interests | The preference, attraction, and excitement of working in a job, to learn and execute tasks. |

| Skills | The competences, technical or social, that are related to an occupation. |

| Experience | The skills that are gained from executing tasks or in jobs over time. |

Social Behavior

Social behavior is how people interact and adapt from a behavioral, emotional, and cognitive standpoints. This component of personality tells about how people function, interact, communicate, make decisions, manage, lead, learn, and more.

Social behavior is the characteristic that we assess the most spontaneously and naturally with our private techniques, but the hardest to get right and with nuances. As for measuring temperature, we may have a good intuition and sense of it, but getting to know the exact room temperature is hard. It requires having an indication of what “exact” and “right” mean, an objective measure with a reference point, and a scale.

Personality is a larger concept than social behavior, sometimes equated to behavior, but also including psychiatric and clinical behaviors. Or personality can include cognitive processes like intelligence that are not part of “social behavior” as we define it here. “Social behavior” includes a large scope of behaviors normally observed in people at work and in society, even if those behaviors are sometimes intense or extreme.

The understanding of social behavior can be approximated by some traits or types. Adaptive profiles from a factor-based approach, as we do at GRI, account for nuances, relative stability, and adaptation that other methods can’t. With appropriate metrics, the adaptive profile additionally informs about social behavior’s intensity, the efforts to adapt, motivation, and engagement in the job.

Social behavior is about achieving results and performing like actors on stage by playing a role. Employees and everyone else do the same, like actors, to meet the expectations in their jobs, as they see them. Mindset can also refer to social behavior, as long as it is clear that it relates to how people specifically think and feel about how they and others behave. Social behavior is omnipresent in our activities. We experience, live them, and have observed them since we were born. They are facing us constantly. When we discuss people, that’s what we talk about. We all have our own sense of how to assess social behavior with our own vocabulary, its nuances, and what we refer to as our private techniques.

Intelligence

Intelligence is a multifaceted concept, encompassing various theoretical frameworks and assessment techniques. It is commonly understood as involving cognitive, verbal and memory capabilities. General Mental Ability (GMA) or intelligence is often measured through standardized tests.

The assessment of intelligence has significantly advanced since the early 1900s with the development of surveys and more sophisticated statistical methods. Early pioneers like Binet and Simon developed scales that introduced the concept of mental age, which later evolved into the use of standard IQ scores that measure specific abilities such as verbal reasoning, numerical reasoning, non-verbal reasoning, and short-term memory. Other influential theories include Spearman's g-factor, which proposes a general intelligence factor alongside specific abilities, and Thurstone's identification of primary mental abilities. Subsequent research by various scholars further expanded the understanding of intelligence. Wechsler's scales, for example, distinguish between verbal, performance, and total IQs, moving beyond the earlier concept of mental age.

Hierarchical models have also emerged, combining different theoretical views to provide a broader understanding of intelligence. These models usually place a general intelligence factor at the top, with more specific factors and core abilities below. Besides traditional cognitive intelligence, the idea of emotional intelligence (EQ) has become more important, highlighting a person's social skills, empathy, and self-awareness. Additionally, Gardner's theory of Multiple Intelligences proposes that individuals have a wide variety of unique intelligences, challenging the idea of a single, universal measure of intelligence. In professional environments, proxy measures like educational achievements are often used to assess intelligence.

We can use our intellect to exert control over our social behavior, and we adapt thanks to it. But our ability to change our behavior in this way is limited. Although IQ is important in many jobs, and it is important to assess intelligence, how we behave and are motivated is distinct and uncorrelated to our IQ. Not only is this clear from research studies, but it is also demonstrated by the adaptive profiles. There is no single profile that is the smartest; anyone can be smart in their own way.

Values

Values are personal beliefs and principles that individuals consider important, shaping their attitudes, behaviors, and decisions across various areas of life, including work, society, religion, and politics. They act as an internal compass, establishing standards for what is viewed as appropriate and desirable.

The concept of value can be likened to interest, although values are generally considered more fundamental and widespread. When deeply rooted, values reflect strong preferences for certain activities and behaviors. In educational settings, values have been connected to academic choices and extracurricular involvement. While they are helpful for emphasizing desired behaviors, measuring values can be difficult because of their subjective and adaptable nature. For example, assigning "moral" values to someone in a particular context suggests their actions are consistent with a broad range of norms within that setting, often validated by selected examples from that individual.

Values, preferences, interests, and social behavior are interconnected. A person's value system offers guidelines for evaluating their own actions and those of others, shaping their attitudes and choices. This complex relationship between concepts is clarified by an individual's adaptive profile, which shows varying levels of behavior intensity and adaptation.

Personal values are also linked to cultural values and societal norms, with corporate values playing a crucial role in establishing expectations and shared understandings within organizations, particularly concerning social behaviors.

The value concept is further developed in this article here.

Abilities

In psychology, the concept of abilities is closely related to that of intelligence. Abilities, as for instance in Thurstone's theory, include verbal comprehension and memory. Mental abilities and cognitive functions like attention and language can be measured by assessment techniques.

In common language, abilities designate the manual or intellectual aptitudes to perform, which often imply inherent gifts or education. For example, a person might have a natural ability for an art, sports, or a language. With that definition, abilities tend to remain stable throughout life and influence how people process information and execute tasks. Abilities differ from skills in that skills are also developed through learning and practice. Abilities are more specific to certain roles, such as high verbal ability, which is valuable for writing, while spatial ability is important for an engineer working in computer-aided design, or being 6-feet tall is valuable for performing in basketball and volleyball.

Interests

Interests in executing some tasks and performing a job are the expression of a preference that excites attention and curiosity. In sports, for example, we speak of an interest in playing football or lacrosse. A person may be interested in working in one company or another, on an activity, with certain people, a team, and a manager, or under certain conditions. What’s more, interests grow over time. What a person is interested in builds through contact with others in real situations within organizations, through internships and apprenticeships, or by occupying and executing a job.

Interests can be of different natures, including social, financial, operational, and ethical. The way an organization balances and responds to these interests is critical for its success. Interest, engagement, and motivation work in concert for a person to perform in a job, overcome challenges, and deliver results efficiently. Interests—and lack of interest—is also informed by an adaptive profile from a behavioral standpoint, and the related emotions to perform in a job.

Skills

Skills refer to the dexterity, speed, precision, and efficiency with which actions or cognition are performed. A skilled person is someone who can perform quickly and well. Skills can be manual and behavioral (overt behavior), or intellectual (covert behavior). We can evidence skills, for instance, in software coding, consulting, mechanical engineering, and accounting as well as in plumbing, welding, painting, or gardening. A skill is flexible and can be taught, practiced, and improved over time.

A skill is measurable and can be demonstrated through qualifications, certifications, and performance assessments. The concept of skills is distinct from that of intelligence or abilities in that it implies that it is acquired through deliberate practice, education, and experience. It similarly applies to managerial and social skills that can be learned and acquired with appropriate context, tools, and learning process.

Experience

Unlike skills and behaviors learned in simulated or classroom settings, those gained through experience result from direct, concrete, and practical contact with facts or events. The reality, intensity, and diversity of those contacts give the skills and behaviors some nuances and meanings rooted in those situations. Being learned in the field, skills and behaviors derived from experience tend to be less general and more closely tied to specific contexts than those acquired more abstractly and deductively off the field.

Experience helps build an intuitive and nuanced appreciation of skills that allow one to act with ease, confidence, and speed. Experience can create agility, both physical and intellectual. Inexperience, on the other hand, may cause errors or delay execution, yet at the same time, it can also bring fresh insights and perspectives. A number of years of experience, however, cannot tell how skills were learned, expressed, or shared. Looking at experience, thus, always needs to be informed by how it builds, something that social behavior, as it is informed by an adaptive profile, can tell.

Experience is particularly important with managerial and social skills, often learned informally, through trial and error, by working with real people and situations. This kind of learning usually takes time. Experience is also essential for all expert manual or intellectual work that demands dexterity and precision. When learning social behavior with GRI’s adaptive profiles, creating meaning on symbols through real, practical, social experience is key, as it has been emphasized in the symbolic interactionism theory. Experience is also central to the concept of enactment, which designates the emergence of knowledge through the presence of individuals in the field.

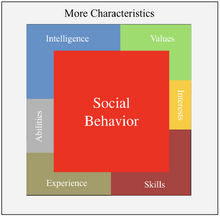

More Characteristics

The characteristics used in organizations are not limited to these seven. Depending on the industry, company, country, and local influences, other concepts are applied that, in some way, overlap with the seven. A brief definition is provided below, including which other concepts they most closely compare to.

Personality

Personality is a broad concept that includes social behavior, intelligence, abilities, etc., and clinical behavior that is assessed by therapists and psychiatrists. The history of personality assessment started from psychiatry and therapy, and later expanded to large-scale recruitments. For this reason and for these applications, personality has been measured with traits. Social behavior, however, accounts for people’s behavior in the “normal” range, which does not include clinical behaviors.[2]

Character

Like personality, character is a broad concept. It combines mental and ethical traits, such as honesty, courage, and integrity. Although character, values, and personality are three distinct concepts, they are interconnected. Personality is centered on how people act, values on beliefs, including moral ones, and character on mental and ethical qualities. All tend to explain how the others do. Social behavior overlaps with the three on how someone behaves, expresses themselves, and also thinks, and feels, including about their values and ethics.

Competences

The competence concept is a generic concept that combines skills, abilities, experiences, and more. Competency models focus on the management of knowledge and other characteristics acquired during training, most often, especially in large organizations, with HRMS (Human Resources Management System), Talent Management platforms, or Learning and development (L&D) platforms. Competency models are used by management and Human Resources to define, train, and use the competencies in recruitment, development, and succession planning. However, competency models underplay the emotions involved in developing behaviors and soft skills and often end up with lists of behavioral attributes that are conflicting. Competency management innately applies to technical rather than social skills.

Attitudes

Attitudes are considered to be antecedent to behaviors and of a cognitive, emotional, or sentimental nature or as a disposition to act. They may vary depending on the context or mood. Behaviors could be anticipated from the knowledge of someone’s attitudes. In everyday language, attitudes and behaviors are often used interchangeably. An attitude cannot be apprehended directly. Based on values and beliefs, attitudes are affected by the forces of the situation before being verbal or non-verbal behaviors and expressed. People most often act in accordance with their attitudes and intentions, which are themselves influenced by their values and motivation. Attitudes can be anticipated from affective, cognitive, and behavioral data as it is measured in the adaptive profile.

Aptitudes

An aptitude is the potential to perform certain activities, whether physical or mental, developed or undeveloped, in a particular domain. In psychology, the concept is close to that of abilities when viewed as inborn, or skills that can be developed by learning, or a combination of the two. In everyday language, aptitudes refer to the possibility of talents or skills for a person to occupy a position. Aptitude refers to a specific area: verbal, spatial, mechanical, business, management, critical thinking, logical reasoning, etc., that can be measured. Students get screened for aptitude through the SAT, GRE, GATE tests, or other certifications.

Knowledge

Knowledge is the information memorized by a person and the ability to use it when dealing with a specific topic. Knowledge often involves the possession of information learned through experience. We speak of knowledge of a foreign language, in computer science, biology, mechanics, management, culture, or any other general or specific field.

The storage and retrieval mechanisms make an unequivocal parallel with a computer’s functioning. A person’s knowledge must be distinguished from doing and acting on it, or the speed of processing information, which fall into the categories of social behavior and intelligence.

Training

By training, we mean classes, masterclasses, studies, courses, or programs attended by someone, which usually result in receiving a diploma or certificate. Training makes it possible to acquire knowledge and skills in a formal way through reading, role play, case studies, homework, presentations, pitches, etc., on a particular topic. A training predisposes a person to then express skills in a real context, adapting those skills and continuing to develop them in the field.

Compared to learning by experience, learning by training is more general, less specific to an environment, but is also more adaptable. It is less nuanced and trustworthy for not having yet been confronted with practical reality and for being only a "laboratory" repertoire.

Culture & language

The culture specifies the context in which a person’s skills, behaviors, and abilities were acquired: country, region, state, time, and other factors that condition the habits, language, food, norms, and protocols. Culture forms attitudes, values, personality, and social habits.

Physical and health

Physical and health characteristics are of particular importance in positions that require them, as for instance for delivery, being an athlete, acting a role on stage, being a fashion models who must have certain aesthetic or physiognomic dispositions.

Talent

Talent is a synonym for aptitude, natural abilities, and skills in a specific domain that can be work-related or not, extending to sports, music, and art in general. Some personality assessments use the word “talent” and a multiple typology approach to assist personal development and coaching, although they focus only on the social behavior component. By that definition, talent is part of someone's character, which needs to be understood and valued.

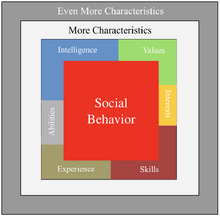

Even More Characteristics

There are many additional characteristics beyond those listed above. Some may be surprising, but all have been observed at GRI over the years, including even esoteric ones, within an organizational context. Some characteristics can easily be obtained by social media or a resumé; Others by interview. Some are ethically and legally questionable. All characteristics can be related to their measurement techniques[3]. Any distinctive characteristic on which an appreciation or judgment is potentially based must be considered.

The reality is that everyone bases their judgment on characteristics that are not explicitly articulated, such as when feeling embarrassment, doubt, or, conversely, confidence and validation, without being able to label the origin of those emotions. Professional recruiters, HR experts, and leaders are not exempt. Competence models and HRIS systems do not store them in files. However, judgment in recruiting, communicating, managing, and organizing is based on some of those characteristics, as it is for everyone.

Studies on leadership highlight characteristics such as appearance or clothing [4]. Bass and Stogdill’s Handbook of Leadership: theory, research, and managerial application. New York: Free Press. First published in 1974.</ref>. Gesture is emphasized in non-verbal communication[5]. Guittet regroups the characteristics of paralanguage into four categories[6]:

- Posture: tone, gestures, bodily contact (handshakes, affectionate gestures, etc.), hand movements, crossing of legs, way of standing at the table, walking or standing in public.

- Body image: clothing choices that go along with fashion trends or not, giving a sign of belonging to a social group.

- Face and mimicry: micro verbal expressions, signs of attention, impatience, astonishment, support, or rejection. Eye movements, gaze fixed, fleeing, or determined, etc.[7]

- Territory: the space that exists between individuals[8]. It also concerns movements, agile, fast, and heavy.

Whether we want it or not, other characteristics get into our evaluations and judgments. It’s most often a matter of being aware of them and being educated to minimize or eliminate bias from them. The list continues:

- Age, height, weight, gender, skin color, and cultural and social origin

- Family and business connections

- Place of residence

- Association, political group, religious group, work team, committee, and more generally, the groups to which one belongs

- Corpulence (morphopsychology): endomorph, mesomorph, or ectomorph[9]

- The shape of the skull (phrenology) or the shape of the face

- Oral expression. The way of expressing oneself in public, in private. The intonations, pitch, or range of the voice. Eloquence

- The written expression. Fluency and writing style

- The astral theme according to the day and hour of birth (astrology)

- A person’s numbers (numerology)

- The hand’s lines, shapes, and features (palmistry)

- Handwriting (graphology)

- Someone’s gaze

- Eyes’ color[10]

- Physiological characteristics such as DNA, blood type (hematopsychology), or fingerprints

- The perception sensitivity in terms of taste, smell, sight, hearing, or touch

- The pleasant or repulsive smell[11]

- Food and body hygiene (dental hygiene analysis is still practiced in some Asian and African countries)

- How one shakes hands, has sweaty hands, opens or closes the door, sits, stands up, etc.

The list of characteristics is not complete, but all of the above have been seen in organizations. Some characteristics are kept private or only partly acknowledged. Attitudes toward oneself and others, along with development strategies, are influenced by the nature and strength of these characteristics and how much people believe in them.

Notes

- ↑ The techniques are analyzed in this other article here.

- ↑ A brief history and prospects of personality assessment is discussed in this article here.

- ↑ The assessment techniques are discussed in this article here

- ↑ Bass B. M. (1990).

- ↑ Watzlavick P., Beavin H., Jackson, D. (1972). Une logique de la communication. Paris, Le Seuil.

- ↑ Guittet, A. (1986). L’entretien. Paris, Armand Colin.

- ↑ Brandler, R., Grinder, J. (1984) Les secrets de la communication. Editions Reuille.

- ↑ Hall, E. T. (1954). The silent language. New York, Doubleday.

- ↑ Kretschmer, E. (1936). Physique and Character. New York: Harcourt.

- ↑ Larsson M, Pedersen NL, Stattin H. Associations between iris characteristics and personality in adulthood. Biol Psychol. 2007 May;75(2):165-75. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2007.01.007. Epub 2007 Feb 1. PMID: 17343974.

- ↑ There is this story about young adult Steve Jobs who had a repulsive smell, that went on for many years; An information obtained from people who worked with him. There are many similar other stories. Such cases are usually handled by managers, or if not HR.