Cybernetic Perspective: Difference between revisions

| Line 46: | Line 46: | ||

Although the cybernetic model can be seen as a better version of the command and control model, with more space given to individual communication, adaptation, feedback, and autonomy, it doesn’t recognize how people cope differently with norms, stress, autonomy, authority, reporting, decision making, communication, and more, all aspects that relate to people’s psychology, their style, preferences, values, motivation, behavior, emotions, or personality. | Although the cybernetic model can be seen as a better version of the command and control model, with more space given to individual communication, adaptation, feedback, and autonomy, it doesn’t recognize how people cope differently with norms, stress, autonomy, authority, reporting, decision making, communication, and more, all aspects that relate to people’s psychology, their style, preferences, values, motivation, behavior, emotions, or personality. | ||

As we evidence with GRI's measures, enforcing a system that’s fundamentally Low 2, High 4, on people who are not and exhibit opposite profiles, will create frustration and | As we evidence with GRI's measures, enforcing a system that’s fundamentally Low 2, High 4, on people who are not and exhibit opposite profiles, will create frustration and result in disengagement over time. The same limitations came with the competency models that emerged at about the same period as cybernetics. Additionally, roles, including leadership roles, may considerably vary depending on situations (think about sales or client service versus accounting) and call for adaptations that, over time, may be beyond someone’s comfort zone and unique capabilities to perform. | ||

Over time, profiles that we measure at GRI with a high 1 or low 4, who can bring and lead radical innovation, will sooner or later feel constrained and leave the organization. Very and extremely High 2s, if misunderstood, will similarly prefer to bring their social skills outside the organization. | Over time, profiles that we measure at GRI with a high 1 or low 4, who can bring and lead radical innovation, will sooner or later feel constrained and leave the organization. Very and extremely High 2s, if misunderstood, will similarly prefer to bring their social skills outside the organization. | ||

Revision as of 03:36, 9 September 2025

Introduction

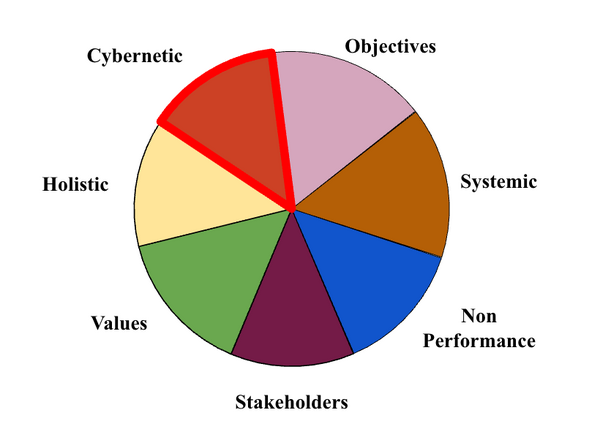

While traditional management systems rely on a top-down, command-and-control hierarchy, cybernetic models view an organization as a self-regulating system that uses feedback to maintain its goals. Performance measurement is seen as an important component of cybernetic models that include goal setting and predictive models to facilitate decisions of alternative actions.

Generalities

The origin of the cybernetic models goes back to the end of the 1970s with the work of Stanford Beer and his Viable System Model (VSM)[1]. With both traditional management systems and cybernetic models, data plays an important role, but with cybernetic models, data is used to drive continuous, adaptive change, whereas in traditional systems, it is used to enforce standards.

The cybernetic model includes the following four considerations:

- Feedback loops: Output information from the system is continuously fed back as input, allowing the organization to self-regulate and adjust course.

- Adaptation: The organization's ability to adapt internally and externally to its environment is critical.

- Complex systems: an organization is a complex, interconnected whole, as opposed to being a collection of isolated, independent parts.

- Decentralized control: Although a central command exists with a cybernetic model, the organization’s units have the autonomy to respond quickly to local changes, as they are capable of making the best-informed decisions based on the most current information.

Cybernetic models attempt to rigorously establish processes for planning, comparing, and evaluating[2] by considering two distinct sets of measures: those defined by the objectives and those required by the predictive models. Traditionally, control systems have emphasized goal-oriented measures[3]. Performance measurement became associated with negative feedback based on the detection of the gaps between the planned objectives and the actual measures of the outcome[4]. In the cybernetic model, measures involve both some aspects of control and others of communication and behavior[5].

Critics of the Cybernetic Model

One of the challenges of the cybernetic model is the difficulty of getting performance data and comparing it to quantifiable and unambiguous standards[6]. From the cybernetic perspective, performance measurement is essentially associated with controlling the achievement of organizational objectives and the implementation of the strategy. Performance measures are implicitly linked to the notion of diagnostic and control systems[7], or formal feedback systems used to control what the organization produces and to correct deviations from a predefined performance standard.

Financial information is associated with traditional planning and control cycles[8]. In traditional management control systems, resources are totally focused on the management of accounting information[9]. Financial measures express the results of decisions in a comparable unit of measurement. They summarize the arbitration cost between resources as well as the cost of unused capacities[10]. Additionally, they are the measure for contractual relations and financial markets[11].

Traditional measurement systems encourage conservatism and a do-it-yourself attitude. Measures such as ROI (Return On Investment) discourage managers from innovating, investing in market share, or developing sources of competitive advantage[12]. They encourage compliance[13]. Moreover, the flexibility and creativity of strategic planning can be ruined by formal control systems[14].

Control systems create a climate that can act against the success of a strategic implementation and its formulation processes. Management control systems can promote or inhibit innovation depending on how they are defined[15]. The construction of a management information and control system requires several decisions concerning the choice of information measured, omitted, and reported. A system that filters inconsistently promotes a fictional satisfaction and clarity that will confirm conventional reasoning. The perception of a manager is limited to the information available[16].

The cybernetic vision's emphasis on financial information has led to errors in calculating production costs, to inadequate control of information, and to the absence of long-term performance measures[17]. Information prepared for external use is inadequate and insufficient for internal use[18].

Limiting Factors

The cybernetic models worked well for the industrial age, but they look out of step with the talents, skills, and engagement in the job that companies are trying to develop[19]. Several factors have been summarized that show the limit of the cybernetic process to respond to change[20]:

- Lack of resources to obtain information in quantity and quality

- Institutionalization of past successes, which inhibits the perception of necessary transformations

- Degree of centralization and concentration of specialists

- Elite values

- Time taken by the hierarchy to find the correct answers and respond.

The limitations of the cybernetic approach come up comparably in other studies[21]:

- Too historical and "looking back"

- Lacks predictive ability to explain future performance

- The reward of behaviors is short-term or on incorrect terms

- Lack of operationality

- Incapable of sending signals for change early enough

- Too aggregated and summarized to be able to guide managerial action

- Reflects functional processes instead of cross-functional processes

- Gives inappropriate guidance for assessing intangible values

The People Challenge

Although the cybernetic model can be seen as a better version of the command and control model, with more space given to individual communication, adaptation, feedback, and autonomy, it doesn’t recognize how people cope differently with norms, stress, autonomy, authority, reporting, decision making, communication, and more, all aspects that relate to people’s psychology, their style, preferences, values, motivation, behavior, emotions, or personality.

As we evidence with GRI's measures, enforcing a system that’s fundamentally Low 2, High 4, on people who are not and exhibit opposite profiles, will create frustration and result in disengagement over time. The same limitations came with the competency models that emerged at about the same period as cybernetics. Additionally, roles, including leadership roles, may considerably vary depending on situations (think about sales or client service versus accounting) and call for adaptations that, over time, may be beyond someone’s comfort zone and unique capabilities to perform.

Over time, profiles that we measure at GRI with a high 1 or low 4, who can bring and lead radical innovation, will sooner or later feel constrained and leave the organization. Very and extremely High 2s, if misunderstood, will similarly prefer to bring their social skills outside the organization.

References

- ↑ Beer, S. (1979). The heart of enterprise: The managerial cybernetics of organization. Wiley.

- ↑ Merchant, K. A., Simons, R. (1986). Research and control in complex organizations: an overview. Journal of Accounting Literature, 5, pp. 183-203.

- ↑ Otley, D. T., Berry, A; J. (1980). Control, organization and accounting. Accounting, Organization and Society, 5, 2, pp. 231-244.

- ↑ Hofstede, G. (1978). The poverty of management control philosophy. Management control philosophy, 3, 3, pp. 450-461.

- ↑ Flamholtz, E. G., Das, T. K., Tsui, A. S. (1985). Toward an integrative framework of organizational control. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 10, 1, pp. 35-50.

- ↑ Ibid, Hofstede, 1978

- ↑ Simons, R. (1995). Levers of control: How managers use innovative control systems to drive strategic renewal. Boston, Harvard Business Schol Press.

- ↑ Nanni, A; J., Dixon, R., Vollmann, T. E. (1992). Integrated performance measurement: management accounting to support the new manufacturing realities. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 4, pp. 1-19.

- ↑ Johnson, H. T., Kaplan, R. (1987). Relevance lost: The rise and fall of management accounting. Boston, Harvard Business School Press.

- ↑ Epstein, M. J., Manzoni, J.-F. (1997). The balanced scorecard and tableau de bord: translating strategy into action. Management Accounting, August, pp. 28-36.

- ↑ Atkinson, A. A., Waterhouse, J. H., Wells, R. B. (1997). A stakeholder approach to strategic performance measurement. Sloan Management Review, Spring, pp. 25-37.

- ↑ Dent, J. F. (1990). Strategy, organisation and control: some possibilities for accounting research. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 15,1-2, pp. 3-25.

- ↑ Roberts J. (1990). Strategy and Accounting in a U.K. Conglomerate. Accounting, Organizations and Society 15, no. 1–2.

- ↑ Ibid, Flamholtz et al., 1985.

- ↑ Ibid, Dent, 1990.

- ↑ Ibid, Flamholtz et al., 1985.

- ↑ Ibid, Johnson, H. T., Kaplan, R., 1987.

- ↑ Ibid, Atkinson, and al., 1997.

- ↑ Kaplan, R. S., Norton, D. P. (1992). The balanced scorecard -Measures that drive performance. Harvard Business Review, January-February, pp. 71-79.

- ↑ Hage, J. (1980). Theories of transformation: form, process and transformation. New York, John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

- ↑ Ittner, C. D., Larcker, D. F. (2001). Assessing empirical research in managerial accounting: a value-based management perspective. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 32, pp. 349-410.