Holistic Perspective: Difference between revisions

m (→Generalities) |

m (→Generalities) |

||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

=Generalities= | =Generalities= | ||

With the holistic model, performance measures are used to facilitate interactions<ref>Simons, R. (1990). The role of management control systems in creating competitive advantage: new perspectives. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 15 (1/2), pp. 127-143.</ref> and to formulate and implement the strategy by revealing the connections between goals, strategy, with indicators of delay and progress<ref>Kaplan, R. S., Norton, D. P. (1992). The balanced scorecard -Measures that drive performance. Harvard Business Review, January-February, pp. 71-79.<br/>Kaplan, R. S., & Norton, D. P. (1996). The balanced scorecard: Translating strategy into action. Harvard Business School Press.</ref> and subsequently help to communicate and operationalize the strategic priorities<ref>Nanni, A; J., Dixon, R., Vollmann, T. E. (1992). Integrated performance measurement: management accounting to support the new manufacturing realities. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 4, pp. 1-19.</ref>. | |||

To stimulate learning and contribute to the formulation of strategies, | The holistic model includes the second-order feedback loop and control goal setting<ref>Hofstede, G. (1981). Management control of public and not-for-profit activities. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 6, 3, pp. 193-211.</ref>. The second loop involves the modification of goals, assumptions, and strategic plans following stakeholders’ learning experience. The role of performance measurement is expanded from a single loop learning dimension to a double loop<ref>Argyris, C, Schon, D. (1978). Organizational learning: A theory of action perspective. Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley.</ref>. Performance measures are seen as encouraging organizational learning, due to their ability to acquire, distribute, interpret, and memorize information<ref>Kloot, L. (1997). Organizational learning and management control systems: responding to environmental change. Management Accounting Research, 8, pp. 47-73.</ref>. The role of performance measures evolves from being a simple component of the planning and monitoring cycle to an independent process that provides a steering function. While in the cybernetic model, the measures account for the distance toward a goal of the planning and control cycles, in the holistic model, the measures account for how the organization progresses in a strategic direction. | ||

To stimulate learning and contribute to the formulation of strategies, measures of the holistic model must focus attention on strategic priorities, create visibility within the organization to ensure coordination, drive action, and improve communication, which is considered essential for learning<ref>Vitale, M. R., Mavrinac, S. C. (1995). How effective is your performance measurement system? Management Accounting, 77, 2, pp. 43-55.</ref>. Leaders and managers can help focus attention and effort toward critical uncertainties by making measurements available about them. Discussions, debates, action plans, ideas, and testing across the organization encourage learning and the emergence of new strategies and tactics. | |||

=Kaplan and Norton Model= | =Kaplan and Norton Model= | ||

Revision as of 16:03, 14 September 2025

Introduction

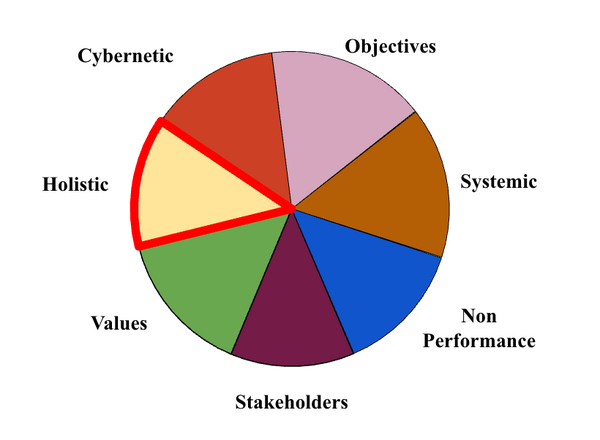

The holistic view of performance is a continuation of the cybernetic model, but differs significantly in its focus on the properties of the organization as a whole and emphasizes the relationships and interactions of its parts[1]. This article is on the performance measures used by holistic models, with an excerpt on Kaplan and Norton’s model.

Generalities

With the holistic model, performance measures are used to facilitate interactions[2] and to formulate and implement the strategy by revealing the connections between goals, strategy, with indicators of delay and progress[3] and subsequently help to communicate and operationalize the strategic priorities[4].

The holistic model includes the second-order feedback loop and control goal setting[5]. The second loop involves the modification of goals, assumptions, and strategic plans following stakeholders’ learning experience. The role of performance measurement is expanded from a single loop learning dimension to a double loop[6]. Performance measures are seen as encouraging organizational learning, due to their ability to acquire, distribute, interpret, and memorize information[7]. The role of performance measures evolves from being a simple component of the planning and monitoring cycle to an independent process that provides a steering function. While in the cybernetic model, the measures account for the distance toward a goal of the planning and control cycles, in the holistic model, the measures account for how the organization progresses in a strategic direction.

To stimulate learning and contribute to the formulation of strategies, measures of the holistic model must focus attention on strategic priorities, create visibility within the organization to ensure coordination, drive action, and improve communication, which is considered essential for learning[8]. Leaders and managers can help focus attention and effort toward critical uncertainties by making measurements available about them. Discussions, debates, action plans, ideas, and testing across the organization encourage learning and the emergence of new strategies and tactics.

Kaplan and Norton Model

Kaplan and Norton constructed the Balanced Scorecard, which incorporates the second-order feedback loop and, as such, can be viewed as supporting the holistic model. It is a generic multi-dimensional chart with the aim of extending financial measures by including three non-financial dimensions related to the company's strategy:

- Customers,

- Internal processes, and

- Innovation, learning, and growth[9].

In addition, this system measures the achievement of the components of the strategic plan. It functions as a management tool[10].

Critics report several weaknesses of the balanced scorecard, such as the absence of procedures to represent the relationship between means and ends, a neglected link with forms of reward, the establishment of information systems and feedback loops that are taken for granted, and the absence of guidelines for setting goals[11].

Some have raised concerns about the temporal dimensions, the relationships between measures, and the interdependence of dimensions[12]. Others have considered the approach incomplete, failing to highlight the contribution of employees, suppliers, and the community in general[13]. Norton and Kaplan themselves have noted the limits of the Balanced Scorecard:

- Unachievable strategy projects,

- Dissociation between strategy and objectives,

- Strategy unrelated to the allocation of resources,

- Solely tactical feedback or an absence of information on the execution and results of the strategy. There is no oversight on the implementation. Returns are only on financial indicators.

More specifically, Norton and Kaplan note the difficulty of objectifying performance measures on a human level. They talk about a lack of indicators[14]. Others have proposed a different approach to a pyramidal performance system[15]. The primary objective here is to link strategy and operations by translating top-down strategic objectives and bottom-up metrics. Objectives and measures are conveyed through four successive levels:

- Corporate vision,

- Business unit,

- Operational departments, and

- Work center.

On these four levels, financial and non-financial measures are used to formulate a strategy and implement it.

Other Critics

In the holistic model, non-financial measures can be problematic because the relationship between improvement in non-financial measures and profits is not clear[16]. In addition, as with all measurement systems, non-standard employee behaviors can be observed to optimize individual performance.

A study based on 23 companies demonstrated that although financial information is still very important, non-financial measures such as customer satisfaction, operational efficiency, employee performance, the environment, innovation, and change are valued by leaders[17]. These factors are incorporated into management reviews and serve to drive organizational change.

Multiple studies show that the use of non-financial measures has an impact on the economic performance of the company[18]. In a context where companies implement non-financial measures such as employee and customer satisfaction, quality, market share, productivity, innovation, etc., these measures are associated with:

- An innovation-oriented strategy,

- Quality-oriented strategy

- Length of product development cycle,

- Industry rule

- Financial strain

The association between non-financial and financial measures is contingent on whether the non-financial data correspond to the characteristics of the organization[19]. Non-financial information emerges as being appropriate for lower-level managers who need direct feedback on operational activities, while financial considerations are more useful for higher-level managers[20].

In complex, competitive, and uncertain rather than stable markets, non-financial measures are described as more satisfactory than financial measures[21]. But the results of this study are tempered by studies that found no relationship between the four dimensions of Kaplan & Norton's balanced scorecard[22]. A reason might be that firms in competitive markets rely on multiple performance measures[23].

In the assessment of the organization's members' non-financial performance, engagement, TinyPulse, and satisfaction surveys are not without problems with regard to the practical use of the information collected. Once a state of non-performance is known, such as stress, the question remains how to prevent it in the future. The non-performance indicator should point to the means that will allow its prevention, control, and resolution in a future similar event.

The measures brought to the interactive control in a holistic perspective should be means for use by managers and leaders, to help focus attention, solve or avoid problems, learn, as well as formulate a strategy on non-financial aspects, including social ones.

Human Limiting Factor

The cybernetic model doesn’t recognize how people cope differently with norms, stress, autonomy, authority, reporting, decision making, communication, and more, all aspects that relate to people’s psychology, their style, preferences, values, motivation, behavior, emotions, or personality. This is an important piece of information that’s generally touched during team building exercises and coaching sessions, but is not available to managers for helping them anticipate, and manage social dynamics, individual interest and preferences.

As the means and actions engaged in a task become more important than only thinking about them, more objective information on a person’s behavior and mindset that’s refined and can be shared becomes a critical element. Making this information available to managers help them and their team be accountable for their collective efforts to perform, appreciate their differences, adjust their behaviors when appropriate, in order to provide the expected results.

In the holistic perspective, GRI’s adaptive profiles provide an understanding of humans’ behavior that is at play when negotiating goals and reaching them. How people feel, think, and behave about the company’s culture, vision, mission, and objectives is also part of the same information coming from the profiles.

By measuring the potential disconnect between a person’s behavior at flow and the organization's expectation, the adaptive profiles can reveal a lack of engagement along with the rationale that accounts for that measure and the means for avoiding its future occurrence. Other aspects of the adaptive profile on creativity, decision making, productivity, motivation, etc., make them particularly well-suited to help holistic systems fulfill their potential.

References

- ↑ Senge, P. M. (1990). The fifth discipline: The art and practice of the learning organization. Doubleday/Currency.

- ↑ Simons, R. (1990). The role of management control systems in creating competitive advantage: new perspectives. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 15 (1/2), pp. 127-143.

- ↑ Kaplan, R. S., Norton, D. P. (1992). The balanced scorecard -Measures that drive performance. Harvard Business Review, January-February, pp. 71-79.

Kaplan, R. S., & Norton, D. P. (1996). The balanced scorecard: Translating strategy into action. Harvard Business School Press. - ↑ Nanni, A; J., Dixon, R., Vollmann, T. E. (1992). Integrated performance measurement: management accounting to support the new manufacturing realities. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 4, pp. 1-19.

- ↑ Hofstede, G. (1981). Management control of public and not-for-profit activities. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 6, 3, pp. 193-211.

- ↑ Argyris, C, Schon, D. (1978). Organizational learning: A theory of action perspective. Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley.

- ↑ Kloot, L. (1997). Organizational learning and management control systems: responding to environmental change. Management Accounting Research, 8, pp. 47-73.

- ↑ Vitale, M. R., Mavrinac, S. C. (1995). How effective is your performance measurement system? Management Accounting, 77, 2, pp. 43-55.

- ↑ Ibid, Kaplan, R. S., & Norton, D. P., 1996.

- ↑ Kaplan, R. S., Norton, D. P. (2001). Transforming the balanced scorecard from performance measurement to strategic management Part I. Accounting Horizons, 15, 1, pp. 87-104.

- ↑ Ibid, Otley, D. (1999).

- ↑ Norreklit, H. (2000). The balance on the balanced scorecard – a critical analysis of some of its assumptions. Management Accounting Research, 11, pp. 65-88.

- ↑ Atkinson, A. A., Waterhouse, J. H., Wells, R. B. (1997). A stakeholder approach to strategic performance measurement. Sloan Management Review, Spring, pp. 25-37.

- ↑ Kaplan, R. S., Norton, D. P. (1998) The balanced Scorecard: Translating strategy into action.

- ↑ Lynch, R. L., Cross, K. F. (1991). Measure up – Yardsticks for continuous improvement. Cambridge, MA, Basil Blackwell.

- ↑ Fisher, J. (1992). Use of nonfinancial performance measures. Journal of Cost Management, Spring, pp.31-38.

- ↑ Lingle, J. H., Schiemann, W. A. (1996). From balanced scorecard to strategic gauges: is measurement worth it? Management review, March, pp. 56-61.

- ↑ Said, A. A., HassabElnaby, H. R., Wier, B. (2003). An Empirical Investigation of the Performance Consequences of Nonfinancial Measures. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 15, pp. 193-223.

Andersen, E., Fornell, C., Lehmann, D. (1994) Customer Satisfaction, market share, and profitability: Findings from Sweden. Journal of Marketing, July, pp. 53-66.

Banker, R. D., Potter, G., Srinivasan, D. (2000). An empirical investigation of an incentive plan that includes nonfinancial performance measures. The accounting review, 75, 1, pp. 65-92.

Foster, G., Gupta, M. (1997). The customer profitability implications of customer satisfaction. Working paper, Stanford University and Washington University. - ↑ Ibid, Said and al., 2003.

- ↑ Dixon, J. R., Nanni, A. J., Vollman, T. E. (1990). The new performance challenge – Measuring operations for world-class competition. Homewood, Illinois, Dow Jones-Irwin.

- ↑ Ibid, Dixon and al., 1990.

- ↑ Hoque, Z, Mia, L., Alam, M. (2001). Market competition, computer-aided manufacturing, and use of multiple performance measures: an empirical study. British Accounting Review, 33, 23-45.

- ↑ Ibid, Hoque and al., 2001.