Performance Models: Difference between revisions

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

==Introduction== | ==Introduction== | ||

This article | This article discusses the different models of organizational performance that have been researched. It introduces how, by being capable of measuring the way people perform, we can stay away from non-performance and create the optimal conditions of group performance. The measures of how individuals function from a cognitive, affective, and behavioral standpoints, the three altogether condensed in a profile, provide the foundation for analyzing and growing individual and organizational performance. | ||

=Management Control= | =Management Control= | ||

Revision as of 05:15, 7 September 2025

Introduction

This article discusses the different models of organizational performance that have been researched. It introduces how, by being capable of measuring the way people perform, we can stay away from non-performance and create the optimal conditions of group performance. The measures of how individuals function from a cognitive, affective, and behavioral standpoints, the three altogether condensed in a profile, provide the foundation for analyzing and growing individual and organizational performance.

Management Control

The traditional, historical, and often implicit understanding of an organization’s performance is that the organization functions like a machine, with its performance measured by efficiency, predictability, and control. With this vision, the goal of the organization is to optimize individual parts and processes to produce a specific, measurable output. Management control, sometimes called "management audit," "management accounting," "managerial control," or simply “management,” depending on the context, has focused on [1]:

- Decision-making for improving the decision-making process through planning and coordination. Planning is about setting strategic and performance goals, monitoring the quality and variety of resources. Coordination is about integrating disparate elements to achieve goals.

- Control for providing feedback and ensuring that the input-output system is properly aligned, and to motivate or evaluate employees.

- Reporting information to managers throughout the organization that relates to their values, preferences, and what employees need to focus their attention and energy on.

- Learning and training for understanding changes in the internal and external environment, as well as the connections between their various components.

- External communication to disseminate information to constituents outside the organization: shareholders, analysts, suppliers, partners, customers, etc.

It’s only progressively that concerns for reporting, learning, and training have gradually emerged. Companies began to differentiate diagnostic from interactive control[2]. While the diagnostic refers to the piloting of routines and the implementation of strategy, interactive control relates to piloting by managers, the focusing of the attention of employees, learning, and the formulation of strategy.

Gradual Evolution

Anthony's seminal work played a major role in the development of management control systems[3]. However, the definition he gave of control systems led to considering these systems as means of control by accounting measures of planning, steering, and integrating mechanisms[4]. The focus was on accounting measures, but the non-financial measures were neglected[5]. The initial objective of accounting management systems, to provide information to facilitate cost control and measure the performance of the organization, was transformed into that of compiling costs with a view to producing periodic financial statements[6].

The role of short-term financial performance measures progressively became inappropriate for the new reality of organizations. The non-financial indicators based on the strategy of the organization were of crucial importance[7]. Gradually, the performance measurement framework began to reconcile the use of financial and non-financial measures. They evolved from a cybernetic vision where the measures are about costs, financial control, planning, and management control, towards a new era reflecting a holistic vision where the performance measures are focused on process efficiency and added value in management through non-financial measures[8].

Performance Models

An organizational performance can be approached through various models, which address aspects of its measurement and control on one hand, and its conceptualization on the other hand. With both perspectives, the terms efficiency or performance can ultimately be considered synonyms[9]. Management control research has traditionally focused on performance measures with the cybernetic model. Considering the human aspects amid non-financial measures has allowed the holistic model to gradually overcome some limitations of the cybernetic model[10].

Other performance models contribute to defining and implementing procedures and performance measures, depending on the context (research, societal, leadership, organizational development, etc.). Several approaches have been proposed for categorizing the performance models. For example, they can be grouped into three categories based on their origins in economic, organizational, and social research[11]. Others have suggested three clear categories: objectives, system, and stakeholders[12].

The different performance perspectives have been regrouped below into seven categories that follow the three grand categories. This grouping enables highlighting different analytical anchor points and limitations. The seven approaches are summarized in the following table:

| Models | Focus |

|---|---|

| Cybernetic | Accounts for the financial and production metrics. |

| Holisitc | Extends from the cybernetic model with individual and social aspects. |

| Objectives | Objectives are set and managed at different levels of the organization. |

| Systems | As a system, an organization’s parts and intangible resources need to be managed. |

| Stakeholders | Stakeholders' characteristics need to be leveraged. |

| Behavioral Values | Extends from the stakeholder model to understand organizations based on individual behavioral values and preferences. |

| Non-performance | Minimize non-performance and ineffectiveness. |

Besides performance models, which only depend on financial, production, and other tangible data, holistic and stakeholder models have increasingly used new research methods and included more sophisticated data and theories about people and their organizations. The nature of this data has evolved over time, from the early days of scientific psychology in the 1900s, which was firmly rooted in behavioral research, to today, where emotions and neuroscience play a significant role.

Personality has been a key concept in many models early on and continues to be widely used in research and practice. In research, it is present in sociology, anthropology, and psychology with its different schools. Personality carries many connotations, though. Despite its extensive use in recruitment, management science, and coaching in day-to-day business, the idea of personality remains coupled to the early days of psychometry, when it was used with deviant behaviors in psychiatry and clinical psychology. Using the personality concept while avoiding its negative connotation remains a constant challenge in practice.

Centrality of Behaviors

Performance models based on actions and values include a behavioral component that makes them especially useful for research and practical applications. Behaviors are observable. We can discuss and analyze them more effectively than abstract concepts, increasing the chances of reaching consensus about what they are and what can be done with them. Behaviors are also a fundamental component of the personality concept. Behavioral traits and typologies have been extensively studied and used, both in recruitment and coaching. Aside from ethical conduct and social responsibility, the behaviors people value—or behavioral values—that they are interested in and will most likely express, are central to how people perform.

Analyzing and classifying behaviors using different models at the individual, team, company, and societal levels uncovers a limited set of behavioral factors. When combined, these factors can help explain behaviors; at GRI, we estimate that up to 90% of observable behaviors in organizations can be explained by four factors. As science progressed, so has our sophistication in analyzing and assessing people and in modeling and representing their behaviors.

Beyond Intuition

As discussed in articles about holistic and stakeholder models, the concepts used for understanding people are numerous: intelligence, mindset, competencies, skills, preferences, styles, beliefs, motivation, drives, emotions, grit, creativity, interests, etc. The list is long. Some concepts are broad and universal, while others are more specific and can only be used for narrow and limited applications. Some are easy to adapt, others are much less so. Some characteristics can be gathered in a few clicks from data collected on the Internet through sophisticated techniques and AI rather than direct observation and intuition.

Discussion on assessment techniques, what they assess, and how they work goes beyond what this article can address. In a few words, though, the survey technique stands apart by its capacity to apply statistics and gather information to produce results that we human beings can’t. We, however, apply our own and limited subjective statistics with our own values and reference points, something we’ve referred to in our research at GRI as our private techniques. Private techniques are valuable individually, but not effective when used with others and for analyzing individual and group performance.

Organizational Performance

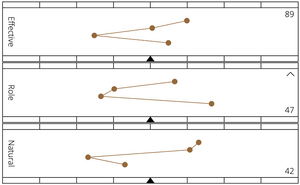

Adaptive profiles, as we measure them at GRI and show in this example here on the right, accurately account for individual performance. The metrics produced reflect an individual's behaviors, affects[13], and mindset that all relate to each other as well as to the individual's preferences, interests, and values.

With adequate content and statistics, the metrics also apply to positions, teams, companies, and even at a societal level. When provided in a condensed way, the results can be learned, memorized, used— and in short, make sense— in multiple situations, where they can bring their value.

The adaptive profile is produced by answering two questions and applying statistics. If you see this profile for the first time, it will not tell you much. It is shown here only to illustrate what it looks like[14]. At an organizational level, the information from the adaptive profiles is regrouped and compared with that of position and group profiles for measuring and analyzing performance.[15]

Notes

- ↑ Simon, H. A. (1954). A formal theory of the employment relationship. Econometrica, 22(3), 293–305.

Simons, R. (2000). Performance measurement and control systems for implementing strategy. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey, Prentice Hall. - ↑ Simons, R. (1990). The role of management control systems in creating competitive advantage: new perspectives. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 15 (1/2), pp. 127-143.

- ↑ Anthony, R. N. (1965). Planning and control systems: A framework for analysis. Division of Research, Graduate School of Business Administration, Harvard University.

- ↑ Langfield-Smith, K. (1997). Management control systems and strategy: A critical review. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 22, 2, pp. 207-232.

- ↑ Otley, D. (1999). Performance management: a framework for management control systems research. Management Accounting Research, 10, pp. 363-382.

- ↑ Johnson, H. T., Kaplan, R. (1987). Relevance lost: The rise and fall of management accounting. Boston, Harvard Business School Press.

- ↑ Kaplan, R. S. (1983). Measuring manufacturing performance: a new challenge for managerial accounting research. The Accounting Review LVIII(4), pp. 686-705.

Eccles, R. G. (1991). The performance measurement manifesto. Harvard Business Review January-February, p. 131-137. - ↑ Ittner, C. D., Larcker, D. F. (2001). Assessing empirical research in managerial accounting: a value-based management perspective. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 32, pp. 349-410.

- ↑ March, J. G., Sutton, R. I. (1997). Organizational Performance as a Dependent Variable. Organization Science. Vol. 8, No. 6, pp. 698-706.

- ↑ Henri, J. F. (2004). Performance measurement and Organizational Effectiveness: Bridging the gap. Managerial Finance. Vol. 30, No. 6, pp 93-123.

- ↑ Vibert C. (2004). Theories of macro organizational behavior: a handbook of ideas and explanations.

- ↑ Campbell, J. P. (1977). On the nature of Organizational effectiveness. In P. S. Godman & J. M. Pennings (Eds.), New perspectives on organizational effectiveness. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Pp. 13-55.

Zammuto, R. F. (1982). Assessing organizational effectiveness: Systems change, adaptation, and strategy. Albany, N.Y.:Suny-Albany Press.

Quinn, R. E., Rohrbaugh, J. (1983). A Spatial Model of Effectiveness Criteria: Towards a Competing Values Approach to Organizational Analysis. Management Science. Vol. 29, No. 3, pp. 363-377.

Cameron, K. S., Whetten, D. A. (1983). Organizational Effectiveness: One model or Several? Preface. Orlando: Academic Press. - ↑ Affect is the more proper technical term, often used interchangeably with emotion.

- ↑ See here some brief information about the adaptive profile

- ↑ See here how the information is operationalized at a group level.

See here how the information is used to calculate strategic and social indicators.