Performance Models

The concept of performance is consistently present in organizations, both in practice and theory. It is this concept that has guided our work at GRI. Can people and organizations better perform with better assessment techniques, and how so? And how should we define performance? To the first question, in short, better assessing people’s social behaviors has provided invaluable insights and new methods to improve individual performance, as well as that of teams and companies. These aspects are mostly addressed in other articles and during GRI’s methods deployment in companies. The present article focuses on answering the second question about defining performance.

Generalities

As discussed below, performance can be seen in different ways. In our case at GRI, we envision organizations’ performance in their social realm by maximizing stakeholders’ flow states and reducing frictions, while enabling the delivery of the results agreed upon by them. Results can be of any kind depending on the context: athletic, financial, engineering, manufacturing, construction, economic, artistic, and even social. Performance is about how individuals act together to deliver the results in a way that optimizes the quality of their relationships, maximizes stakeholders’ satisfaction, and minimizes underperformance.

It’s the kind of performance that shows in sports, where team members perform collectively—not only physically to deliver results, but also from a behavioral, cognitive, and emotional standpoint, all three concomitantly. The team's leader has an important role in how the players are recruited, managed, and organized. But each team member can make a difference, too, for the better or the worse, in delivering the expected results. Performing in sports may lead to earning a prize if this is the standard that stakeholders have set. This metaphor highlights important aspects of performance where one needs to engage, grow, and maintain skills, and is also dependent on others for their individual performance. Just like in sports, performance depends on how we assess each other when strategizing, planning, recruiting, managing, interacting, and organizing our collective efforts. How people assess one another is central to all aspects that lead to performance, which is why it became central to our research at GRI, applying advanced social science methods to analyze assessment techniques and their impacts on performance.

Our investigations have covered private individual techniques—those we use ourselves—esoteric methods still employed by many, and modern approaches that have emerged with recent advances in statistics and computing, including the Internet and AI. We analyzed their use, content, and effects. We also developed our own technique to overcome the limitations we were witnessing, raising the quality, precision, and utility of the measurement. The adaptive profiles, the metric resulting from GRI’s assessment, became central for redefining and implementing performance from a social standpoint, and other forms of performance happening concomitantly. This article explores different approaches to understanding performance. It offers insights into how performance can be significantly improved by enhancing the quality of individual and group assessment.

An Evolution From Management Control

The traditional, historical, and often implicit understanding of an organization’s performance is that the organization functions like a machine, with its performance measured by efficiency, predictability, and control. The goal of the organization is to optimize individual parts and processes to produce a specific, measurable output. With this vision in mind, management control, sometimes called "management audit," "management accounting," "managerial control," or simply “management,” depending on the context, has focused on:

- Decision-making for improving the decision-making process through planning and coordination. Planning is about setting strategic and performance goals, monitoring the quality and variety of resources. Coordination is about integrating disparate elements to achieve goals.

- Control for providing feedback and ensuring that the input-output system is properly aligned, and to motivate or evaluate employees.

- Reporting information to managers throughout the organization that relates to their values, preferences, and what employees need to focus their attention and energy on.

- Learning and training for understanding changes in the internal and external environment, as well as the connections between their various components.

- External communication to disseminate information to constituents outside the organization: shareholders, analysts, suppliers, partners, customers, etc.

It is only since the early 1960s that concerns for reporting, learning, and training have gradually emerged. Companies began to differentiate diagnostic from interactive control. While the diagnostic refers to the piloting of routines and the implementation of strategy, interactive control relates to piloting by managers, the focusing of the attention of employees, learning, and the formulation of strategy.

Anthony's seminal work played a major role in the development of management control systems. However, the definition he gave of control systems led to considering these systems as means of control by accounting measures of planning, steering, and integrating mechanisms. The focus was on accounting measures, but the non-financial measures were neglected. The initial objective of accounting management systems, to provide information to facilitate cost control and measure the performance of the organization, was transformed into that of compiling costs with a view to producing periodic financial statements.

The role of short-term financial performance measures progressively became inappropriate for the new reality of organizations. The non-financial indicators based on the strategy of the organization were of crucial importance. Gradually, the performance measurement framework began to reconcile the use of financial and non-financial measures. They evolved from a cybernetic vision where the measures are about costs, financial control, planning, and management control, towards a new era reflecting a holistic vision where the performance measures are focused on process efficiency and added value in management through non-financial measures.

A Challenging Construct

There is little consensus on the concept of performance. Its multiple definitions and shifting aspects are problematic. The notion of performance covers certain necessities. It is well related to the notion of achieving objectives and constraints. Five points of consensus in performance research can be summarized:

- The concept of organizational performance is central and cannot be ignored.

- Different performance models are useful in different circumstances. Their usefulness depends on the goals and constraints that the organization imposes on itself in evaluating its performance. They are complementary.

- The conceptualization of what a performing organization stands for is changing as the view of it as a social contract evolves through metaphors. Metaphors make it possible to be aware of new phenomena and performance variables that previous metaphors would not have yet revealed.

- The criteria for selecting performance indicators are based on individual values and preferences, which are difficult to identify, even by people themselves, and often contradictory between individuals. Depending on who is involved, a different set of criteria can be identified. What people say they prefer and what their behaviors suggest they prefer are not always the same thing.

- Questions of performance are mainly brought about through the problems encountered rather than through theories. The problems of an organization’s performance are not theoretical but practical and respond to criteria.

Importantly, performance is a construct. A construct is an abstraction that cannot be pointed to, counted, or directly observed. It exists only because it is inferred from observable phenomena, but it has no objective reality. It is a mental abstraction used to understand ideas or interpretations. A concept, unlike a construct, can be linked to an empirical reality. It can be defined and precisely described by observable events. Constructs, however, cannot be defined in this way. Their boundaries cannot be drawn exactly.

As a construct, performance cannot have a meaning that is definitively known and apprehended by a single model. One model includes elements not found in the other models; each of the models has a value. However, none has sufficient explanatory power to supplant the others. Asking whether an organization is performing or not does not mean much before specifying different aspects that can be relatively independent of each other. Such a construct allows a wide variety of organizations to be simultaneously judged to be successful despite contradictory characteristics. It makes it possible to include criteria that would not have been judged as important by one stakeholder, but which may ultimately turn out to be essential by others.

A too narrow definition of performance limits this advantage. The complexity and ambiguity of organizational performance are necessary to reflect the complexity and ambiguity of organizations. Some have argued that the concept of performance is more for engineering than science. Organizations could be seen as entities involved in a multitude of objectives, which in turn show only a weak ordering of their general preference. At the same time, the underlying preferences depend on stakeholders' values whose positions are accepted by others.

A primary task in questions related to performance is to identify suitable indicators and standards. Closely related is the issue of measurements, which concerns managers and evaluators the most, all with a sense of what they consider effective, even if these ideas are hard to define and put into practice.

Understanding Performance with Metaphors

The conceptualization of what a performing organization stands for is changing as the view of it evolves through new metaphors. Metaphors have been used as powerful tools for redefining organizational performance, helping to shift the underlying assumptions and perspectives about how an organization functions. The use of metaphors has helped move the focus away from the traditional mechanistic views toward more dynamic, holistic, or ecological ones. It has enabled organizations to be aware of new phenomena, problems, or potential gains, and variables that other metaphors could not reveal.

For instance, using the symphony orchestra metaphor, performance involves bringing together diverse individual talents, a shared vision, and a conductor who manages harmony through coordinated effort to create a cohesive and powerful whole. With the metaphor from economics, organizations have transaction costs, which are the expenses incurred when making any economic exchange. These costs are not for the goods or services themselves, but for searching the information, bargaining, writing and enforcing contracts, and monitoring performance.

Metaphors, however, do not venture into how individuals function and interact, but by means of their intellect and bounded rationality, with little consideration of their emotions. Metaphors help shift the focus from individuals to the quality of the collective output, but abstract individual nuances, preventing us from understanding how each individual behaves, adapts, and performs in the system.

Performance Models

An organizational performance can be approached through various models, which address, on one hand, aspects of its measurement and control, and on the other hand, its conceptualization. Both perspectives refer to it using the terms efficiency or performance, which ultimately can be considered synonyms. Management control research has traditionally focused on performance measures with the cybernetic model. Considering the human aspects amid non-financial measures has allowed the holistic model to gradually overcome some limitations of the cybernetic model model.

Other performance models each contribute to defining and implementing procedures and performance measures, depending on the context (research, societal, leadership, organizational development, etc.) and the authors. Several approaches have been proposed for categorizing these performance models. For example, they can be grouped into three categories based on their origins in economic, organizational, and social research. Others have suggested three clear categories: objectives, system, and stakeholders.

The different performance perspectives have been regrouped below into seven categories according to these three grand categories. This grouping enables highlighting different analytical anchor points and limitations. The seven approaches are summarized in the following table:

| Models | Focus |

|---|---|

| Cybernetic | Accounts for the financial and production metrics. |

| Holisitc | Extends from the cybernetic model with individual and social aspects. |

| Objectives | Objectives are set and managed at different levels of the organization. |

| Systems | As a system, an organization’s parts and intangible resources need to be managed. |

| Stakeholders | Stakeholders' characteristics need to be leveraged. |

| Actions and Values | Extends from the stakeholder model to understand organizations based on individual behavioral values and preferences. |

| Non performance | Minimize non-performance and ineffectiveness. |

Besides performance models, which only depend on financial, production, and other tangible data, holistic and stakeholder models have increasingly used new research methods and included more sophisticated data and theories about people and their organizations. The nature of this data has evolved over time, from the early days of scientific psychology in the 1900s, which was firmly rooted in behavioral research, to today, where emotions and neuroscience play a significant role.

Personality has been a central concept since early on and continues to be widely used in research models and practice. In research, it is present in sociology, anthropology, and psychology, and its different schools. Personality carries many connotations. Despite its extensive use in recruitment, management science, and coaching in day-to-day business, the idea of personality remains linked to the early days of psychometry, when it was used to measure deviant behaviors in psychiatry and clinical psychology. For this reason, we are careful when using the personality concept to avoid its negative connotation, while continuing to take the most from its research.

The performance models based on actions and values include a behavioral component that makes them especially useful for research and practical applications. Behaviors are observable, which allows us to discuss and analyze them more effectively, increasing the chances of reaching consensus about what they are and what can be done with them. They are also a fundamental part of the personality concept, including within organizations. Behavioral traits and typologies have been extensively studied and utilized, both in recruitment and coaching. Aside from ethical conduct and social responsibility, the behaviors people value—or behavioral values—that they are emotionally interested in and most likely to express are central to how people perform.

Analyzing and classifying behaviors using different models at the individual, team, company, and societal levels uncovers a limited set of behavioral factors. When combined, these factors can help explain behaviors; at GRI, we estimate that up to 90% of observable behaviors in organizations are explained by four factors. As science progressed, so has our sophistication in analyzing and assessing people and in modeling and representing their behaviors. As discussed in articles about holistic and stakeholder models, the concepts used by models are numerous: intelligence, competencies, skills, preferences, styles, beliefs, motivation, drives, emotions, creativity, interests, and more. Some are broad and universal, while others are narrow and applicable only in limited contexts. Some are easy to change or adapt; others are less so. Some characteristics can be gathered in a few clicks on the Internet; others can only be attained through more sophisticated techniques than direct observation and intuition, or even AI, by making assumptions based on the Internet.

Discussion on assessment techniques, what they assess, and how they work goes beyond what can be addressed here in this article. In a few lines, a key aspect of the survey technique is that it can produce results by applying statistics that we can’t do as human beings. We, however, apply our own and limited subjective statistics with our own values and reference points, something we’ve referred to in our research at GRI as our private techniques. Private techniques may be valuable for their owners, but not effective enough when applied to group performance.

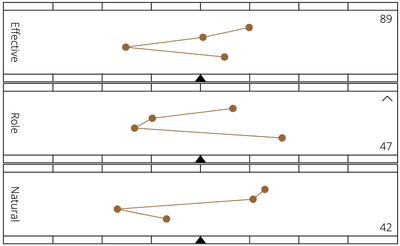

GRI’s survey measures people's performance from a behavioral value standpoint. The metrics produced account for the affective, emotional, and cognitive aspects, which can all relate to those of individual interests, values, and behaviors. With adequate content and statistics, the metrics also apply to positions, teams, companies, and even at a societal level.When provided in a condensed way, the results can be learned, memorized, and used— or in short, make sense— in multiple situations, where they can bring their value. The result is the adaptive profile, as the one here on the right. It is produced by answering two questions and applying statistics. If you see this profile for the first time, it will not tell you much. It is shown here only to illustrate what it looks like. The discussion forward is about how those profiles inform about one's performance and that of an organization.

Performance at Heart

The adaptive profiles are made up of three graphs which inform about a person’s most natural way to perform (Natural, the graph at the bootom), the perception to adapt to the environment (Role, the graph in the middle) and how both graphs translate into the effective way to perform (Effective, the graph on teh top), the one that most probably will be observed. Each graph shows four factors (the four small dots) and scales (above and below the graphs) that indicate the strength and direction of behavior. From a functional point of view, an adaptive profile assesses a person’s mode of action, its focus, and intensity. It’s not about their personality traits or types, although those ideas can be inferred from the adaptive profiles.

Like any instrument, trusting the results requires some initial effort, which one might be willing to put in if they see benefits. Having some understanding of how people function, behave, and adapt can then open new perspectives at an organizational level. This can help improve individual efficiency and performance, while also boosting a group's overall performance, reducing its chance of underperformance, and consequently benefiting each member.

The information from the adaptive profiles focuses on performance, offering a perspective on people that goes beyond their interests, skills, and intellect. It considers how they function fully with their brains, hearts, and guts within the context of their unique experiences and environment. By helping people get into their flow state, adapt to the environment in an engaging way, and clearly identify how they will underperform, the adaptive profiles redefine how individuals and their organizations can enhance performance. The practicality of this information makes it applicable in many settings close to where decisions and actions regarding people are made.

What happens with those measures is no different from other measures of, let’s say, time, temperature, distance, and weight, once their measurement is available with an instrument and can be trusted. Their results can be used in a way that enhances the objectivity of the concepts being measured and allows for their use in ways that were not possible before. Of critical importance is the quality and practicality of the measure, which are discussed in other articles. Operationalizing the performance construct with the adaptive profiles allows for viewing the various models of performance from a new perspective and to make the most of them to benefit organizations and their stakeholders.

Operationalising Performance Measures

The adaptive profiles possess several characteristics that are important for understanding, implementing, and managing individual and organizational performance. The six key characteristics of the measures included in the profiles are as follows:

- The behavioral nature of the measures and, therefore, their ability to be observed, shared, and learned from.

- The capacity to concentrate significant meaning in profiles with visual representations that allow for comparisons, continued learning, and their use alongside other variables to understand people and their organizations.

- The adaptive and dynamic qualities for understanding people in context.

- The central nature of how people perform and act in context, which is at the crossroads of their preferences, interests, how they think and feel about how they behave, their beliefs about who they are, and how they connect to their environment.

- The accuracy, validity, and usefulness of the measures for numerous applications.

- The universality and reliability of the measures over time for predicting individual and organizational behaviors in context.

The measures invite asking new questions about people and their organizations to keep them away from being disengaged and ineffective. At the same time, they assist in adapting one’s behaviors more effectively and using the information where and whenever it’s needed, often in the hands and minds of managers, to improve or help adjust behaviors within the ranges of variability specific to each person. With practice, the measures become a reliable source of understanding people and situations, helping to find new creative solutions for individual and organizational challenges. These solutions can better align with people’s behavioral values. The measures are used not only to explain why and how a behavior occurred but also to predict future behaviors, along with the thoughts and feelings associated with them.

Whether a person is suitable for a job also depends on whether their adaptive profile aligns with their role, which is not just about intelligence, skills, or experience. Instead, it’s about how those other characteristics develop and adapt, which the adaptive profiles can reveal. The mismatches seen between the Natural and Role profiles or between the Natural and Effective profiles and the position’s profile are likely to lead to practical adjustments at the individual level, in their role, management environment, with colleagues and reports, for future growth within their current position or in other roles.

The produced metric reveals what would otherwise be unseen and misleading, and reflects a person’s many qualities and growth journey. Other characteristics, such as physical traits, are naturally observable. This is not true for the information shown by the adaptive profiles. The measures provide a standard for comparing behaviors among individuals, including those from different cultures, or between people, roles, teams, and their organization.

The meaning of adjectives that describe our behaviors is naturally ambiguous. Using factorial analysis with statistics has allowed us to focus meaning on specific factors. In fact, the profiles and concepts created by reducing the lexicon also enable the reconstruction of new 'concentrates' of meaning. This adaptive model can be applied to all types of behaviors, concepts, or other individual characteristics to evaluate them in behavioral and probabilistic terms: such a way of being creative, delegating, communicating, directing, teaching, learning, solving complex problems, etc. By the limits of variability indicated in the measurements, it is possible to focus on individual actions while avoiding strong adaptation and desengagement, which will most probably lead to dissatisfaction and lack of productivity. When there is interest in improving oneself and an organization's performance, using the adaptive profiles starts to make sense, and their applications are limitless.