Performance Models

Assessing people’s social behaviors and values more precisely than our intuition alone can do has provided invaluable insights for improving individual and organizational performance. How assessment techniques, including our private ones, differ from each other and are used is discussed in other articles and practically during GRI’s deployment. This article focuses on how organizational performance can possibly be assessed and redefined.

Generalities

An organization’s performance can be viewed in different ways. At GRI, we see it in its social realm by minimizing unnecessary frictions and delivering the results agreed upon by stakeholders. The nature of the results can vary depending on the context: athletic, financial, engineering, manufacturing, construction, economic, artistic, social, and more. As in sports, each team member can greatly influence the achievement of expected results. The team leader plays a crucial role in how athletes are recruited, managed, and organized. Excelling in sports may lead to winning a prize if that’s the standard set by stakeholders. Being efficient by reaching a flow state or being in the zone can significantly boost the team’s performance.

This metaphor emphasizes key aspects of performance where individuals must engage, develop, and maintain skills, and their success is also influenced by others. As in sports, performance relies on how we evaluate each other during strategizing, planning, recruiting, managing, interacting, and coordinating collective efforts. The way people evaluate one another is central to all aspects that contribute to performance. This is one reason why assessment techniques became a research focus at GRI, something we have done by applying advanced social science methods.

Our investigations have covered private individual techniques—those we use ourselves—esoteric methods still employed by many, and modern approaches that have emerged with recent advances in statistics and computing, including the Internet and AI. We analyzed their use, content, and effects. We also developed our own technique to overcome the limitations we were witnessing, raising the quality, precision, and utility of the measurement. The adaptive profiles, the metric resulting from GRI’s assessment, became central for redefining and implementing performance from a social standpoint, and other forms of performance happening concomitantly.

This article explores different approaches to understanding performance. It offers insights into how performance can be significantly improved by enhancing the quality of individual and group assessment.

An Evolution From Management Control

The traditional, historical, and often implicit understanding of an organization’s performance is that the organization functions like a machine, with its performance measured by efficiency, predictability, and control. The goal of the organization is to optimize individual parts and processes to produce a specific, measurable output. With this vision in mind, management control, sometimes called "management audit," "management accounting," "managerial control," or simply “management,” depending on the context, has focused on[1]:

- Decision-making for improving the decision-making process through planning and coordination. Planning is about setting strategic and performance goals, monitoring the quality and variety of resources. Coordination is about integrating disparate elements to achieve goals.

- Control for providing feedback and ensuring that the input-output system is properly aligned, and to motivate or evaluate employees.

- Reporting information to managers throughout the organization that relates to their values, preferences, and what employees need to focus their attention and energy on.

- Learning and training for understanding changes in the internal and external environment, as well as the connections between their various components.

- External communication to disseminate information to constituents outside the organization: shareholders, analysts, suppliers, partners, customers, etc.

It is only since the early 1960s that concerns for reporting, learning, and training have gradually emerged. Companies began to differentiate diagnostic from interactive control[2]. While the diagnostic refers to the piloting of routines and the implementation of strategy, interactive control relates to piloting by managers, the focusing of the attention of employees, learning, and the formulation of strategy.

Anthony's seminal work played a major role in the development of management control systems[3]. However, the definition he gave of control systems led to considering these systems as means of control by accounting measures of planning, steering, and integrating mechanisms[4]. The focus was on accounting measures, but the non-financial measures were neglected[5]. The initial objective of accounting management systems, to provide information to facilitate cost control and measure the performance of the organization, was transformed into that of compiling costs with a view to producing periodic financial statements[6]. The role of short-term financial performance measures progressively became inappropriate for the new reality of organizations. The non-financial indicators based on the strategy of the organization were of crucial importance[7]. Gradually, the performance measurement framework began to reconcile the use of financial and non-financial measures. They evolved from a cybernetic vision where the measures are about costs, financial control, planning, and management control, towards a new era reflecting a holistic vision where the performance measures are focused on process efficiency and added value in management through non-financial measures[8].

Performance Models

An organizational performance can be approached through various models, which address, on one hand, aspects of its measurement and control, and on the other hand, its conceptualization. Both perspectives refer to it using the terms efficiency or performance, which ultimately can be considered synonyms[9]. Management control research has traditionally focused on performance measures with the cybernetic model. Considering the human aspects amid non-financial measures has allowed the holistic model to gradually overcome some limitations of the cybernetic model[10].

Other performance models each contribute to defining and implementing procedures and performance measures, depending on the context (research, societal, leadership, organizational development, etc.) and the authors. Several approaches have been proposed for categorizing these performance models. For example, they can be grouped into three categories based on their origins in economic, organizational, and social research[11]. Others have suggested three clear categories: objectives, system, and stakeholders[12].

The different performance perspectives have been regrouped below into seven categories according to these three grand categories. This grouping enables highlighting different analytical anchor points and limitations. The seven approaches are summarized in the following table:

| Models | Focus |

|---|---|

| Cybernetic | Accounts for the financial and production metrics. |

| Holisitc | Extends from the cybernetic model with individual and social aspects. |

| Objectives | Objectives are set and managed at different levels of the organization. |

| Systems | As a system, an organization’s parts and intangible resources need to be managed. |

| Stakeholders | Stakeholders' characteristics need to be leveraged. |

| Actions and Values | Extends from the stakeholder model to understand organizations based on individual behavioral values and preferences. |

| Non performance | Minimize non-performance and ineffectiveness. |

Besides performance models, which only depend on financial, production, and other tangible data, holistic and stakeholder models have increasingly used new research methods and included more sophisticated data and theories about people and their organizations. The nature of this data has evolved over time, from the early days of scientific psychology in the 1900s, which was firmly rooted in behavioral research, to today, where emotions and neuroscience play a significant role.

Individual Performance at Large

Personality has been a central concept since early on and continues to be widely used in research models and practice. In research, it is present in sociology, anthropology, and psychology, and its different schools. Personality carries many connotations. Despite its extensive use in recruitment, management science, and coaching in day-to-day business, the idea of personality remains linked to the early days of psychometry, when it was used to measure deviant behaviors in psychiatry and clinical psychology. For this reason, we are careful when using the personality concept to avoid its negative connotation, while continuing to take the most from its research.

Centrality of Behaviors

The performance models based on actions and values include a behavioral component that makes them especially useful for research and practical applications. Behaviors are observable, which allows us to discuss and analyze them more effectively, increasing the chances of reaching consensus about what they are and what can be done with them. They are also a fundamental part of the personality concept, including within organizations. Behavioral traits and typologies have been extensively studied and utilized, both in recruitment and coaching. Aside from ethical conduct and social responsibility, the behaviors people value—or behavioral values—that they are emotionally interested in and most likely to express are central to how people perform.

Factor Approach

Analyzing and classifying behaviors using different models at the individual, team, company, and societal levels uncovers a limited set of behavioral factors. When combined, these factors can help explain behaviors; at GRI, we estimate that up to 90% of observable behaviors in organizations are explained by four factors. As science progressed, so has our sophistication in analyzing and assessing people and in modeling and representing their behaviors.

Making the Measures Available

As discussed in articles about holistic and stakeholder models, the concepts used by models are numerous: intelligence, competencies, skills, preferences, styles, beliefs, motivation, drives, emotions, creativity, interests, and more. Some are broad and universal, while others are narrow and applicable only in limited contexts. Some are easy to change or adapt; others are less so. Some characteristics can be gathered in a few clicks on the Internet; others can only be attained through more sophisticated techniques than direct observation and intuition, or even AI, by making assumptions based on the Internet.

Beyond Intuition

Discussion on assessment techniques, what they assess, and how they work goes beyond what can be addressed here in this article. In a few lines, a key aspect of the survey technique is that it can produce results by applying statistics that we can’t do as human beings. We, however, apply our own and limited subjective statistics with our own values and reference points, something we’ve referred to in our research at GRI as our private techniques. Private techniques may be valuable for their owners, but not effective enough when applied to group performance.

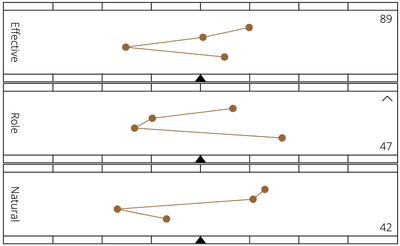

Assessing Individual Performance

GRI’s survey measures people's performance from a behavioral value standpoint. The metrics produced account for the affective, emotional, and cognitive aspects, which can all relate to those of individual interests, values, and behaviors. With adequate content and statistics, the metrics also apply to positions, teams, companies, and even at a societal level. When provided in a condensed way, the results can be learned, memorized, and used— or in short, make sense— in multiple situations, where they can bring their value. The result is the adaptive profile, as the one here on the right. It is produced by answering two questions and applying statistics. If you see this profile for the first time, it will not tell you much. It is shown here only to illustrate what it looks like. The discussion forward is about how those profiles inform about one's performance and that of an organization.

Operationalising Performance Measures

The adaptive profiles possess several characteristics that are important for understanding, implementing, and managing individual and organizational performance. The six key characteristics of the measures included in the profiles are as follows:

- The behavioral nature of the measures and, therefore, their ability to be observed, shared, and learned from.

- The capacity to concentrate significant meaning in profiles with visual representations that allow for comparisons, continued learning, and their use alongside other variables to understand people and their organizations.

- The adaptive and dynamic qualities for understanding people in context.

- The central nature of how people perform and act in context, which is at the crossroads of their preferences, interests, how they think and feel about how they behave, their beliefs about who they are, and how they connect to their environment.

- The accuracy, validity, and usefulness of the measures for numerous applications.

- The universality and reliability of the measures over time for predicting individual and organizational behaviors in context.

The measures invite asking new questions about people and their organizations to keep them away from being disengaged and ineffective. At the same time, they assist in adapting one’s behaviors more effectively and using the information where and whenever it’s needed, often in the hands and minds of managers, to improve or help adjust behaviors within the ranges of variability specific to each person. With practice, the measures become a reliable source of understanding people and situations, helping to find new creative solutions for individual and organizational challenges. These solutions can better align with people’s behavioral values. The measures are used not only to explain why and how a behavior occurred but also to predict future behaviors, along with the thoughts and feelings associated with them.

Whether a person is suitable for a job also depends on whether their adaptive profile aligns with their role, which is not just about intelligence, skills, or experience. Instead, it’s about how those other characteristics develop and adapt, which the adaptive profiles can reveal. The mismatches seen between the Natural and Role profiles or between the Natural and Effective profiles and the position’s profile are likely to lead to practical adjustments at the individual level, in their role, management environment, with colleagues and reports, for future growth within their current position or in other roles.

The produced metric reveals what would otherwise be unseen and misleading, and reflects a person’s many qualities and growth journey. Other characteristics, such as physical traits, are naturally observable. This is not true for the information shown by the adaptive profiles. The measures provide a standard for comparing behaviors among individuals, including those from different cultures, or between people, roles, teams, and their organization.

The meaning of adjectives that describe our behaviors is naturally ambiguous. Using factorial analysis with statistics has allowed us to focus on specific factors. In fact, the profiles and concepts created by reducing the lexicon also enable the reconstruction of new 'concentrates' of meaning. This adaptive model can be applied to all types of behaviors, concepts, or other individual characteristics to evaluate them in behavioral and probabilistic terms: such a way of being creative, delegating, communicating, directing, teaching, learning, solving complex problems, etc. By the limits of variability indicated in the measurements, it is possible to focus on individual actions while avoiding strong adaptation and desengagement, which will most probably lead to dissatisfaction and lack of productivity. When there is interest in improving oneself and an organization's performance, using the adaptive profiles starts to make sense, and their applications are limitless.

Notes

- ↑ Simon, H. A. (1954). A formal theory of the employment relationship. Econometrica, 22(3), 293–305.

Simons, R. (2000). Performance measurement and control systems for implementing strategy. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey, Prentice Hall. - ↑ Simons, R. (1990). The role of management control systems in creating competitive advantage: new perspectives. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 15 (1/2), pp. 127-143.

- ↑ Anthony, R. N. (1965). Planning and control systems: A framework for analysis. Division of Research, Graduate School of Business Administration, Harvard University.

- ↑ Langfield-Smith, K. (1997). Management control systems and strategy: A critical review. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 22, 2, pp. 207-232.

- ↑ Otley, D. (1999). Performance management: a framework for management control systems research. Management Accounting Research, 10, pp. 363-382.

- ↑ Johnson, H. T., Kaplan, R. (1987). Relevance lost: The rise and fall of management accounting. Boston, Harvard Business School Press.

- ↑ Kaplan, R. S. (1983). Measuring manufacturing performance: a new challenge for managerial accounting research. The Accounting Review LVIII(4), pp. 686-705.

Eccles, R. G. (1991). The performance measurement manifesto. Harvard Business Review January-February, p. 131-137. - ↑ Ittner, C. D., Larcker, D. F. (2001). Assessing empirical research in managerial accounting: a value-based management perspective. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 32, pp. 349-410.

- ↑ March, J. G., Sutton, R. I. (1997). Organizational Performance as a Dependent Variable. Organization Science. Vol. 8, No. 6, pp. 698-706.

- ↑ Henri, J. F. (2004). Performance measurement and Organizational Effectiveness: Bridging the gap. Managerial Finance. Vol. 30, No. 6, pp 93-123.

- ↑ Vibert C. (2004). Theories of macro organizational behavior: a handbook of ideas and explanations.

- ↑ Campbell, J. P. (1977). On the nature of Organizational effectiveness. In P. S. Godman & J. M. Pennings (Eds.), New perspectives on organizational effectiveness. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Pp. 13-55.

Zammuto, R. F. (1982). Assessing organizational effectiveness: Systems change, adaptation, and strategy. Albany, N.Y.:Suny-Albany Press.

Quinn, R. E., Rohrbaugh, J. (1983). A Spatial Model of Effectiveness Criteria: Towards a Competing Values Approach to Organizational Analysis. Management Science. Vol. 29, No. 3, pp. 363-377.

Cameron, K. S., Whetten, D. A. (1983). Organizational Effectiveness: One model or Several? Preface. Orlando: Academic Press.