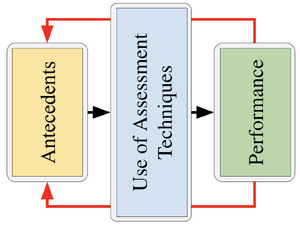

General Framework

Introduction

The general framework presented in this article is used at GRI in research on the impact of using assessment techniques on organizational performance. It was initially developed to answer the specific question on how social behavior measurements used by executives improve and organziation performance. The specific question was subsequently enlarged to include other users, techniques and usage, incluing parallel techniques for their predominant use in organizations.

The board applicability of the framework and the unique qualities of the adapetive profiles being used have opened up new avenues to research on leadership and organizational development, as well as other aspects such as the nature of social behaviors and the effective learning of social-skills.

Throughout its three phases, the framework's development continued to adhere to academic standards, with the intention that it be tested and used by parties other than GRI, or adapted to new, specific projects. GRI’s framework is thus fully disclosed on this wiki, including its research methodology, model creation, coding, hypothesis building, testing, and validation mechanisms with their variables and indicators.

The GRI framework is regularly used to to better monitor the deployment GRI tools and techniques in organizations, to better capture the numerous variables at play, potential applications, and learning on the field.. After presenting the framework, the article discusses its development and offers a critique of the challenges ahead.

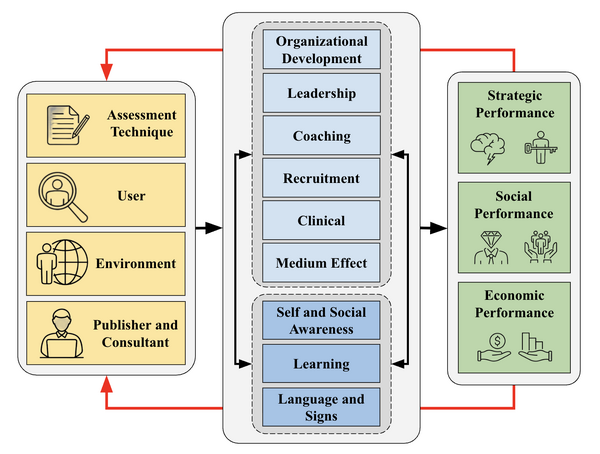

Framework Design

The general framework is represented below. It includes nine independent variables on the use of assessment techniques (in blue), regrouped into two subsets: practical uses in organizational development, leadership, coaching, recruitment, and clinical settings, and abstract uses in self- and social-awareness, learning, language, and signs that span all practical uses.

The framework includes four antecedent variables (in yellow): the assessment technique, the user, the environment in which the method is used, and the publisher and consultant.

The dependent variables (in green) include three variables. Strategic performance is measured by the gap between the strategic intent for organizational performance and its realization. Social performance measures how people adapt and engage at the group level by interacting with others. Economic performance includes typical KPIs and KRIs that may, for instance, be of a production or financial nature. Strategic and Social performances are contingent upon how individual performance is measured with the adaptive profiles.

The red arrows from dependent to antecedent variables indicate that learning from the framework continues to deepen understanding and refine the antecedent variables. Again, this framework applies not only to the GRI survey and the deployment of adaptive profiles but also to any other technique[1].

Framework’s Development

The first framework was built from 2002 to 2006, with a thesis demonstrating the positive relationship between leaders' and managers' use of personality assessments and organizational performance. Assessment techniques in the early 2000s were continually evolving. Software packages were providing increasingly powerful capabilities for data analysis and statistical computation. The development of the framework followed social research academic standards, notably those of Miles and Huberman[2], Wacheux[3], and Eisenhardt[4].

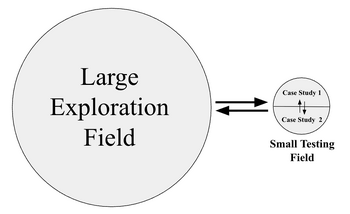

A large-scale exploration field comprised 1,116 participants from 501 companies whom Frederic Lucas-Conwell met between 1995 and 2006. The organizations were from varied industries, different countries, and of various sizes[5]. It allowed the collection of information on the uses of assessment techniques, their users, and their effects. The framework was subsequently tested in two organizations, which are referred to as case studies in the small testing field. The research process followed the attached diagram on the right. The arrows represent the interactions between the large and small fields.

The observations from the large field were from primary sources: direct observations of companies and their people, and secondary sources: testimony from publishing companies, consultants, journalists, and various documents collected. The interaction between the large and small fields happened once the first framework was built. Observations from the small field and between the two case studies stimulated new observations in the large field, and vice versa, as we moved back and forth between the large and small fields only after the testing phase began.

The framework was successfully tested on case studies of the small testing field[6]. The concepts, assessment techniques, and theories supporting the frameworks in psychology, sociology, social interactionism, organizational behavior, leadership, and semiotics (the analysis and philosophy of signs) have been documented[7].

The first framework laid the foundation for the second phase, which lasted from 2006 to 2012. Personality research has firmly confirmed the universality and nature of the factors employed. The Internet enabled unprecedented levels of data collection, usage, and analysis. Although observations were saturated after the first framework was created, the rise of coaching, advancements in well-being, and the use of typology assessments created new opportunities for observation. After 2005, major exploration areas became increasingly focused on the U.S., particularly the Bay Area.

The new framework from phase 2 included assessment techniques such as parallel techniques, rather than relying solely on personality assessments, as in the first phase. The inclusion of new techniques allowed broader analysis and comparison of assessment techniques. As identified in the first phase, assessment techniques both compete with and complement one another.

In 2012, the GRI (Growth Resources Institute) was launched, offering a new platform for quality assessment, marking the start of the third phase. The GRI survey was developed by removing important limitations identified in personality assessment techniques during phases 1 and 2. With the advent of AI and the increasing number of assessment techniques that can be quickly developed, we were prompted to publish more on the origins of the adaptive profiles and methods derived from using GRI’s framework. The publication has helped to demonstrate how assessment techniques differ, how their differences are reflected in their use, and what different impacts users with different roles could expect from them.

Other Insights from the Framework

Working with the framework has enabled to research into specific topics, with, as a consequence, new insights into the tools and methods being developed at GRI. The topics include the following:

- Clarifying the nature of social behavior, its adaptive, engagement, and performance elements. Social behavior is one facet of personality that is challenged by numerous techniques on the market. It’s usually presented in many different ways. This needed to be clarified.

- Evidencing the importance of symbolic features and language created by assessment techniques. Those elements can often be structural obstacle to the accuracy of assessment techniques and their use in strategic applications.

- Setting new criteria for benchmarking assessment techniques. Standards were established in the early years of clinical psychology for use by clinicians and psychiatrists. Focusing on users clarified the conditions under which techniques deliver on their promise to improve performance at the strategic level.

- Refining the concepts of social and strategic performance based on social behavior measured by the adaptive profile, and how they benefit other forms of performance.

- Devising the GRI assessment, adaptive profiles, and other tools used at GRI on jobs and teams, by removing limiting factors uncovered with competing techniques, and by continually testing the framework.

- Elaborating courses for learning and using the adaptive profiles, in the same way a language is learned.

Opening New Perspectives

Perhaps the most significant barrier to the use of the GRI framework, including its tools and techniques, is the belief that only specialists or people in HR and coaches can use them. This belief is rooted in the use of esoteric techniques such as astrology, tarot readings, and crystal balls since the beginning of time, and the practice of using a medium of some sort to provide counsel. In these situations, the quality of the technique is of little importance relative to the story built around it. It occurs similarly with tools based on types used in coaching, as well as with others based on traits for recruitment. Statistics are often part of the story that help exploit the medium effect, regardless of their quality.

The challenge for the market is to recognize that, when adequately built, tools are necessary to address essential, costly human challenges in organizations, beyond subjective and intuitive limitations. Only when this new knowledge becomes part of a company’s culture can it deliver its full potential.

Knowledge of the framework and adaptive profiles is available on this wiki, but only through rigorous learning can the GRI framework language be learned through concrete examples and a step-by-step, incremental path. Often, users begin their journey by comparing the learning to what they have seen in other systems. Because of the nature and scope of the adaptive profiles, the deconstruction and reconstruction of meaning at play, it cannot be learned any other way. The process is counterintuitive, but that’s what makes it ultimately beneficial.

The same learning is required for users as when conducting research with the GRI framework using adaptive profiles. Doing so requires the rapid development of new skills and the acquisition of a new language.

Notes

- ↑ See more information here in the wiki about various assessment techniques used in organizations.

- ↑ Miles M.B., Huberman A.M. (2003). Qualitative data analysis; De Boeck University.

- ↑ Wacheux, F. (1996). Méthodes Qualitatives de Recherche en Gestion. Economica.

- ↑ Eisenhardt K. M. (1989). Building Theories from Case Study Research, Academy of Management Review, vol. 14, n° 4, pp. 532-550.

- ↑ See here the details of the large exploration field and small testing field.

- ↑ See here nore information about the two case studies used to test the first framework.

- ↑ See here about the theories beind the framework, and here about the operationslizations of the concepts.