Command and Control Perspective

Introduction

The traditional, historical, and often implicit understanding of an organization’s performance is that it functions like a machine, with its performance measured by efficiency, predictability, and control. This article reviews some aspects of this traditional vision and the evolution of management control systems that came along.

Generalities

With the original top-down, command-and-control vision, management's role is to optimize an organization’s individual parts and processes to produce a specific, measurable output. The origin of management control goes back to the beginning of time.

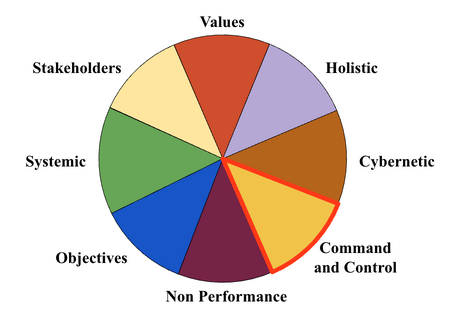

The foundations of traditional management control accelerated in the 18th century through the Industrial Revolution and became scientific at the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th century, with, among others, the work of Frederick W. Taylor, Henry L. Gantt, and Henri Fayol. Management control of that period can be seen as the foundation for the other cybernetic[1] and holistic [2] models that emerged subsequently in the 1950s and 1990s.

Management Control Basics

Management control, sometimes called "management audit," "management accounting," "managerial control," or simply “management,” depending on the context, has focused on:

- Strategic Planning for improving the decision-making process through planning and coordination. Planning is about setting strategic and performance goals, monitoring the quality and variety of resources. Coordination is about integrating disparate elements to achieve goals.

- Controlling, for providing feedback and ensuring that the input-output system is properly aligned, ensuring resources are used effectively and efficiently, tasks are carried out effectively and efficiently as well, to achieve objectives, and to motivate or evaluate employees.

It’s only progressively and more recently, since the 1990s, that the following concerns emerged and started being incorporated into management control models[3]

- Reporting information to managers throughout the organization that relates to their values, preferences, and what employees need to focus their attention and energy on.

- Learning and training for understanding changes in the internal and external environment, as well as the connections between their various components.

- External communication to disseminate information to constituents outside the organization: shareholders, analysts, suppliers, partners, customers, etc.

Companies began to differentiate diagnostic from interactive control. While the diagnostic refers to the piloting of routines and the implementation of strategy, interactive control relates to piloting by managers, the focusing of the attention of employees, learning, and the formulation of strategy.

Critics

Robert Anthony's seminal work in the 1960s played a major role in the progress of management control systems[4]. However, the definition he gave of control systems led to considering these systems as means of control by accounting measures of planning, steering, and integrating mechanisms[5]. The focus was on accounting measures, but the non-financial measures were neglected[6]. The initial objective of accounting management systems, to provide information to facilitate cost control and measure the performance of the organization, was transformed into that of compiling costs with a view to producing periodic financial statements[7].

The role of short-term financial performance measures progressively became inappropriate for the new reality of organizations. The non-financial indicators based on the strategy of the organization were of crucial importance[8]. From the 1970s to the 1980s, the performance measurement framework began to gradually try to reconcile the use of financial and non-financial measures. The models evolved to a cybernetic vision where the measures are about costs, financial control, planning, and management control, and subsequently to a new era reflecting a holistic vision where the performance measures are focused on process efficiency and added value in management through non-financial measures[9].

Human Limiting Factor

Despite being challenged by the era of knowledge workers, the traditional command and control model continues to be valid in many situations. That’s the case, for instance, for large military and administrative structures, repetitive tasks in predictable environments, or when decision-making and execution by a team need to happen fast under a leader’s command, such as SWAT teams in both business and the military, or in crisis and emergency situations.

The traditional management control system applies to work being subcontracted or executed remotely by another entity, which itself may apply a different system. Although not directly accounted for by the company's system, the human factor of the subcontractor is generally expected to be managed professionally, according to the company's norms and values; values that vary from industry to industry and country to country.

How do people feel about and are productive in a command-and-control system while being in charge as a manager or as a team member? This question can be answered by knowing their adaptive profile and the profile of their job, as we measure them at GRI. For knowledge workers, this system will most often cause inefficiency and disengagement.

Paternalism, which emerged during the same period as the scientific management control systems, and whose principles revolve around a patriarchal, family-like, hierarchical structure, is still present in our days. If valid, including for moral and ethical reasons, it would equally benefit from a better understanding of how people function in a command-and-control system.

References

- ↑ See more about the cybernetic model here.

- ↑ See more about the holistic model here.

- ↑ Simon, H. A. (1954). A formal theory of the employment relationship. Econometrica, 22(3), 293–305.

Simons, R. (2000). Performance measurement and control systems for implementing strategy. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey, Prentice Hall. - ↑ Anthony, R. N. (1965). Planning and control systems: A framework for analysis. Division of Research, Graduate School of Business Administration, Harvard University.

- ↑ Langfield-Smith, K. (1997). Management control systems and strategy: A critical review. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 22, 2, pp. 207-232.

- ↑ Otley, D. (1999). Performance management: a framework for management control systems research. Management Accounting Research, 10, pp. 363-382.

- ↑ Johnson, H. T., Kaplan, R. (1987). Relevance lost: The rise and fall of management accounting. Boston, Harvard Business School Press.

- ↑ Kaplan, R. S. (1983). Measuring manufacturing performance: a new challenge for managerial accounting research. The Accounting Review LVIII(4), pp. 686-705.

Eccles, R. G. (1991). The performance measurement manifesto. Harvard Business Review January-February, p. 131-137. - ↑ Ittner, C. D., Larcker, D. F. (2001). Assessing empirical research in managerial accounting: a value-based management perspective. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 32, pp. 349-410.