Command and Control Perspective: Difference between revisions

m (Flc moved page Command and Control to Command and Control Perspective without leaving a redirect) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[File:Performance_Cybernetic.png|right|600px]] | [[File:Performance_Cybernetic.png|right|600px]] | ||

=Introduction= | =Introduction= | ||

The traditional, historical, and often implicit understanding of an organization’s performance is that the organization functions like a machine, with its performance measured by efficiency, predictability, and control. | The traditional, historical, and often implicit understanding of an organization’s performance is that the organization functions like a machine, with its performance measured by efficiency, predictability, and control. This article reviews some aspects of this traditional vision, which, although challenged by the knowledge worker era, continues to be valid to a large extent for large military and administrative structures, or when work is distantly executed by outside contractors. | ||

=Generalities= | =Generalities= | ||

Management control, sometimes called "management audit," "management accounting," "managerial control," or simply “management,” depending on the context, has focused on | With the original top-down, command and control vision, the role of management is to optimize an organization’s individual parts and processes in order to produce a specific, measurable output. The origin of management control came hand in hand with this vision, which goes back to the beginning of time. It has evolved along with the understanding of how people work, learn, deliver, and react to the output expected from them. | ||

<ref>Simon, H. A. (1954). A formal theory of the employment relationship. Econometrica, 22(3), 293–305.<br/>Simons, R. (2000). Performance measurement and control systems for implementing strategy. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey, Prentice Hall.</ref> | |||

The foundations of traditional management control accelerated in the 18th century through the Industrial Revolution and became scientific at the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th century, with, among others, the work of Frederick W. Taylor, Henry L. Gantt, and Henri Fayol. Management control of that period can be seen as the foundation for the other cybernetic<ref>[[Cybernetic_Perspective|cybernetic model here]]</ref> and holistic <ref>[[Holistic_Perspective|holistic model here]]</ref> models that subsequently emerged at the turn of the 21st century. | |||

Management control, sometimes called "management audit," "management accounting," "managerial control," or simply “management,” depending on the context, has focused on: | |||

* '''Strategic Planning''' for improving the decision-making process through planning and coordination. Planning is about setting strategic and performance goals, monitoring the quality and variety of resources. Coordination is about integrating disparate elements to achieve goals. | |||

* '''Controlling''', for providing feedback and ensuring that the input-output system is properly aligned, ensuring resources are used effectively and efficiently, tasks are carried out effectively and efficiently as well, to achieve objectives, and to motivate or evaluate employees. | |||

It’s only progressively and more recently, since the 1990s, that the following concerns emerged and started being incorporated into management control models<ref>Simon, H. A. (1954). A formal theory of the employment relationship. Econometrica, 22(3), 293–305.<br/>Simons, R. (2000). Performance measurement and control systems for implementing strategy. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey, Prentice Hall.</ref> | |||

* Reporting information to managers throughout the organization that relates to their values, preferences, and what employees need to focus their attention and energy on. | * Reporting information to managers throughout the organization that relates to their values, preferences, and what employees need to focus their attention and energy on. | ||

* Learning and training for understanding changes in the internal and external environment, as well as the connections between their various components. | * Learning and training for understanding changes in the internal and external environment, as well as the connections between their various components. | ||

* External communication to disseminate information to constituents outside the organization: shareholders, analysts, suppliers, partners, customers, etc. | * External communication to disseminate information to constituents outside the organization: shareholders, analysts, suppliers, partners, customers, etc. | ||

Companies began to differentiate diagnostic from interactive control. While the diagnostic refers to the piloting of routines and the implementation of strategy, interactive control relates to piloting by managers, the focusing of the attention of employees, learning, and the formulation of strategy. | |||

=Critics= | =Critics= | ||

Anthony's seminal work played a major role in the | Robert Anthony's seminal work in the 1960s played a major role in the progress of management control systems<ref>Anthony, R. N. (1965). Planning and control systems: A framework for analysis. Division of Research, Graduate School of Business Administration, Harvard University.</ref>. However, the definition he gave of control systems led to considering these systems as means of control by accounting measures of planning, steering, and integrating mechanisms<ref>Langfield-Smith, K. (1997). Management control systems and strategy: A critical review. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 22, 2, pp. 207-232.</ref>. The focus was on accounting measures, but the non-financial measures were neglected<ref>Otley, D. (1999). Performance management: a framework for management control systems research. Management Accounting Research, 10, pp. 363-382.</ref>. The initial objective of accounting management systems, to provide information to facilitate cost control and measure the performance of the organization, was transformed into that of compiling costs with a view to producing periodic financial statements<ref>Johnson, H. T., Kaplan, R. (1987). Relevance lost: The rise and fall of management accounting. Boston, Harvard Business School Press.</ref>. | ||

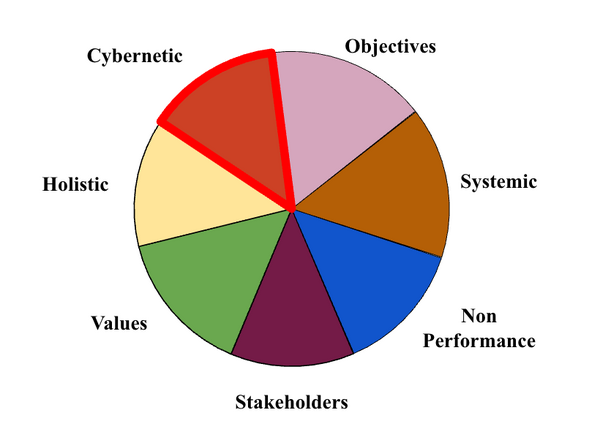

The role of short-term financial performance measures progressively became inappropriate for the new reality of organizations. The non-financial indicators based on the strategy of the organization were of crucial importance<ref>Kaplan, R. S. (1983). Measuring manufacturing performance: a new challenge for managerial accounting research. The Accounting Review LVIII(4), pp. 686-705.<br/>Eccles, R. G. (1991). The performance measurement manifesto. Harvard Business Review January-February, p. 131-137.</ref>. Gradually, the performance measurement framework began to reconcile the use of financial and non-financial measures. They evolved from a cybernetic vision where the measures are about costs, financial control, planning, and management control, towards a new era reflecting a holistic vision where the performance measures are focused on process efficiency and added value in management through non-financial measures<ref>Ittner, C. D., Larcker, D. F. (2001). Assessing empirical research in managerial accounting: a value-based management perspective. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 32, pp. 349-410.</ref>. | The role of short-term financial performance measures progressively became inappropriate for the new reality of organizations. The non-financial indicators based on the strategy of the organization were of crucial importance<ref>Kaplan, R. S. (1983). Measuring manufacturing performance: a new challenge for managerial accounting research. The Accounting Review LVIII(4), pp. 686-705.<br/>Eccles, R. G. (1991). The performance measurement manifesto. Harvard Business Review January-February, p. 131-137.</ref>. Gradually, the performance measurement framework began to reconcile the use of financial and non-financial measures. They evolved from a cybernetic vision where the measures are about costs, financial control, planning, and management control, towards a new era reflecting a holistic vision where the performance measures are focused on process efficiency and added value in management through non-financial measures<ref>Ittner, C. D., Larcker, D. F. (2001). Assessing empirical research in managerial accounting: a value-based management perspective. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 32, pp. 349-410.</ref>. | ||

Revision as of 19:20, 13 September 2025

Introduction

The traditional, historical, and often implicit understanding of an organization’s performance is that the organization functions like a machine, with its performance measured by efficiency, predictability, and control. This article reviews some aspects of this traditional vision, which, although challenged by the knowledge worker era, continues to be valid to a large extent for large military and administrative structures, or when work is distantly executed by outside contractors.

Generalities

With the original top-down, command and control vision, the role of management is to optimize an organization’s individual parts and processes in order to produce a specific, measurable output. The origin of management control came hand in hand with this vision, which goes back to the beginning of time. It has evolved along with the understanding of how people work, learn, deliver, and react to the output expected from them.

The foundations of traditional management control accelerated in the 18th century through the Industrial Revolution and became scientific at the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th century, with, among others, the work of Frederick W. Taylor, Henry L. Gantt, and Henri Fayol. Management control of that period can be seen as the foundation for the other cybernetic[1] and holistic [2] models that subsequently emerged at the turn of the 21st century.

Management control, sometimes called "management audit," "management accounting," "managerial control," or simply “management,” depending on the context, has focused on:

- Strategic Planning for improving the decision-making process through planning and coordination. Planning is about setting strategic and performance goals, monitoring the quality and variety of resources. Coordination is about integrating disparate elements to achieve goals.

- Controlling, for providing feedback and ensuring that the input-output system is properly aligned, ensuring resources are used effectively and efficiently, tasks are carried out effectively and efficiently as well, to achieve objectives, and to motivate or evaluate employees.

It’s only progressively and more recently, since the 1990s, that the following concerns emerged and started being incorporated into management control models[3]

- Reporting information to managers throughout the organization that relates to their values, preferences, and what employees need to focus their attention and energy on.

- Learning and training for understanding changes in the internal and external environment, as well as the connections between their various components.

- External communication to disseminate information to constituents outside the organization: shareholders, analysts, suppliers, partners, customers, etc.

Companies began to differentiate diagnostic from interactive control. While the diagnostic refers to the piloting of routines and the implementation of strategy, interactive control relates to piloting by managers, the focusing of the attention of employees, learning, and the formulation of strategy.

Critics

Robert Anthony's seminal work in the 1960s played a major role in the progress of management control systems[4]. However, the definition he gave of control systems led to considering these systems as means of control by accounting measures of planning, steering, and integrating mechanisms[5]. The focus was on accounting measures, but the non-financial measures were neglected[6]. The initial objective of accounting management systems, to provide information to facilitate cost control and measure the performance of the organization, was transformed into that of compiling costs with a view to producing periodic financial statements[7].

The role of short-term financial performance measures progressively became inappropriate for the new reality of organizations. The non-financial indicators based on the strategy of the organization were of crucial importance[8]. Gradually, the performance measurement framework began to reconcile the use of financial and non-financial measures. They evolved from a cybernetic vision where the measures are about costs, financial control, planning, and management control, towards a new era reflecting a holistic vision where the performance measures are focused on process efficiency and added value in management through non-financial measures[9].

References

- ↑ cybernetic model here

- ↑ holistic model here

- ↑ Simon, H. A. (1954). A formal theory of the employment relationship. Econometrica, 22(3), 293–305.

Simons, R. (2000). Performance measurement and control systems for implementing strategy. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey, Prentice Hall. - ↑ Anthony, R. N. (1965). Planning and control systems: A framework for analysis. Division of Research, Graduate School of Business Administration, Harvard University.

- ↑ Langfield-Smith, K. (1997). Management control systems and strategy: A critical review. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 22, 2, pp. 207-232.

- ↑ Otley, D. (1999). Performance management: a framework for management control systems research. Management Accounting Research, 10, pp. 363-382.

- ↑ Johnson, H. T., Kaplan, R. (1987). Relevance lost: The rise and fall of management accounting. Boston, Harvard Business School Press.

- ↑ Kaplan, R. S. (1983). Measuring manufacturing performance: a new challenge for managerial accounting research. The Accounting Review LVIII(4), pp. 686-705.

Eccles, R. G. (1991). The performance measurement manifesto. Harvard Business Review January-February, p. 131-137. - ↑ Ittner, C. D., Larcker, D. F. (2001). Assessing empirical research in managerial accounting: a value-based management perspective. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 32, pp. 349-410.