Performance Models: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[File: | [[File:Performance_Models_Evidenced.png|right|450px]] | ||

==Introduction== | ==Introduction== | ||

Revision as of 06:07, 15 September 2025

Introduction

This article introduces different models of organizational performance that have been researched over the past decades and the trend observed toward a better understanding of how individuals function and perform in groups.

When appropriately measured and condensed into results that can be used on a broad range of subjects related to a company’s strategy and day-to-day operations, the measures provide the new foundation for raising organizational performance to new levels.

Performance Models

An organizational performance can be approached through various models, which address aspects of its measurement and control on one hand, and its conceptualization on the other hand. With both perspectives, the terms efficiency or performance can ultimately be considered synonyms[1]. Management control research has traditionally focused on performance measures with the cybernetic model. Considering the human aspects amid non-financial measures has allowed the holistic model to gradually overcome some limitations of the cybernetic model[2].

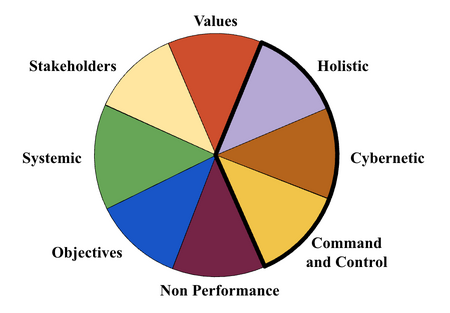

Other performance models contribute to defining and implementing procedures and performance measures, depending on the context (research, societal, leadership, organizational development, etc.). Several approaches have been proposed for categorizing the performance models. For example, they can be grouped into three categories based on their origins in economic, organizational, and social research[3]. Others have suggested three clear categories: objectives, system, and stakeholders[4].

The different performance perspectives have been regrouped below into seven categories that follow the three grand categories. This grouping enables highlighting different analytical anchor points and limitations. The seven approaches are summarized in the following table:

Besides performance models, which only depend on financial, production, and other tangible data, holistic and stakeholder models have increasingly used new research methods and included more sophisticated data and theories about people and their organizations. The nature of this data has evolved over time, from the early days of scientific psychology in the 1900s, which was firmly rooted in behavioral research, to today, where emotions and neuroscience play a significant role.

Personality has been a key concept in many models early on and continues to be widely used in research and practice. In research, it is present in sociology, anthropology, and psychology with its different schools. Personality carries many connotations, though. Despite its extensive use in recruitment, management science, and coaching in day-to-day business, the idea of personality remains coupled to the early days of psychometry, when it was used with deviant behaviors in psychiatry and clinical psychology. Using the personality concept while avoiding its negative connotation remains a constant challenge in practice.

Centrality of Social Behaviors

Performance models based on actions and values include a behavioral component that makes them especially useful for research and practical applications. Behaviors are observable. We can discuss and analyze them more effectively than abstract concepts, increasing the chances of reaching consensus about what they are and what can be done with them. Behaviors are also a fundamental component of the personality concept. Behavioral traits and typologies have been extensively studied and used, both in recruitment and coaching. The behaviors that people value, are interested in, and will most likely express, also inform us about how they function and can perform.

Being capable of analyzing behaviors using different models at the individual, team, company, and societal levels uncovers a limited set of behavioral factors. When combined, these factors can help explain behaviors; at GRI, we estimate that up to 90% of observable behaviors in organizations can be explained by four factors. As science progressed, so has our sophistication in analyzing and assessing people and in modeling and representing their behaviors.

Beyond Intuition

As discussed in articles about holistic and stakeholder models, the concepts used for understanding people are numerous: intelligence, mindset, competencies, skills, preferences, styles, beliefs, motivation, drives, emotions, grit, creativity, interests, etc. The list is long. Some concepts are broad and universal, while others are more specific and can only be used for narrow and limited applications. Some are easy to adapt, others are much less so. Some characteristics can be gathered in a few clicks from data collected on the Internet through sophisticated techniques and AI rather than direct observation and intuition.

Discussion on assessment techniques, what they assess, and how they work goes beyond what this article can address. In a few words, though, the survey technique stands apart by its capacity to apply statistics and gather information to produce results that we human beings can’t. We, however, apply our own and limited subjective statistics with our own values and reference points, something we’ve referred to in our research at GRI as our private techniques. Private techniques are valuable individually, but not effective when used with others and for analyzing individual and group performance.

Organizational Performance

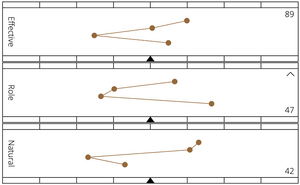

Adaptive profiles, as we measure them at GRI and show in this example here on the right, accurately account for how people perform in context. The metrics represent, in a condensed way, how someone thinks, feels, and behaves. The three relate to each other. In other words it’s how someone functions based on what they think and feel about how they act. The metrics are people’s mindset about their preferences, interests, values, how they socialize, and communicate.

With adequate content and statistics, the metrics also apply to positions, teams, companies, and even at a societal level. When provided in a condensed way, the results can be learned, memorized, and used— or in short, make sense— in multiple situations, where they can bring their value.

The adaptive profile is produced by answering two questions and applying statistics. If you see this profile for the first time, it will not tell you much. It is shown here only to illustrate what it looks like[5].

At an organizational level, the information from the adaptive profiles is regrouped and compared with that of position and group profiles for measuring and analyzing performance.[6]

Notes

- ↑ March, J. G., Sutton, R. I. (1997). Organizational Performance as a Dependent Variable. Organization Science. Vol. 8, No. 6, pp. 698-706.

- ↑ Henri, J. F. (2004). Performance measurement and Organizational Effectiveness: Bridging the gap. Managerial Finance. Vol. 30, No. 6, pp 93-123.

- ↑ Vibert C. (2004). Theories of macro organizational behavior: a handbook of ideas and explanations.

- ↑ Campbell, J. P. (1977). On the nature of Organizational effectiveness. In P. S. Godman & J. M. Pennings (Eds.), New perspectives on organizational effectiveness. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Pp. 13-55.

Zammuto, R. F. (1982). Assessing organizational effectiveness: Systems change, adaptation, and strategy. Albany, N.Y.:Suny-Albany Press.

Quinn, R. E., Rohrbaugh, J. (1983). A Spatial Model of Effectiveness Criteria: Towards a Competing Values Approach to Organizational Analysis. Management Science. Vol. 29, No. 3, pp. 363-377.

Cameron, K. S., Whetten, D. A. (1983). Organizational Effectiveness: One model or Several? Preface. Orlando: Academic Press. - ↑ See here some brief information about the adaptive profile

- ↑ See here how the information is operationalized at a group level.

See here how the information is used to calculate strategic and social indicators.