Performance Models: Difference between revisions

| (137 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[File: | [[File:Performance_Models.png|right|400px]] | ||

=Introduction= | |||

This article | This article discusses various models of organizational performance that have been studied over the past decades, and the trend toward a better understanding of how individuals function and perform in groups, which is essential to other forms of performance. | ||

When accurately measured and condensed into adaptive profiles applicable across a wide range of topics related to a company’s strategy and daily operations, these measures provide a new foundation for improving organizational performance. | |||

=Performance Models= | =Performance Models= | ||

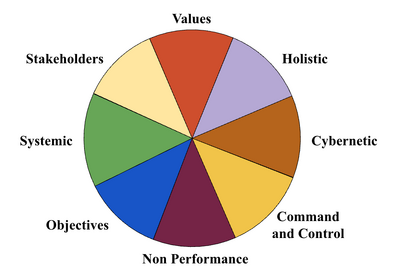

Organizational performance can be approached through various models, which address aspects of its measurement and control on the one hand, and its conceptualization on the other. | |||

Until the 1980s, management control research had focused on performance measures within the cybernetic model, an extension of the more popular command-and-control model that had dominated until the 1950s. Considering new individual and cultural factors alongside non-financial measures has enabled the holistic model to gradually overcome some limitations of the cybernetic model<ref>Henri, J. F. (2004). Performance measurement and Organizational Effectiveness: Bridging the gap. Managerial Finance. Vol. 30, No. 6, pp 93-123.</ref>. Since the 2000s, thanks to capabilities from software platforms, the Internet, and later AI, Management Control System (MCS) packages have integrated and powered management control systems as an integral part of managing organizations, most often aligned with holistic models. The three grand models are summarized in this table and detailed in separate articles. | |||

{| class="wikitable" style="margin: auto;" | {| class="wikitable" style="margin: auto;" | ||

|+ | |+ Performance Management | ||

! Models !! Focus | ! Models !! Focus | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Cybernetic ||Accounts for the financial and production metrics. | | [[Command_and_Control_Perspective | Command and Control]] || Traditional hierarchical top-down approach, with original management control systems for planning and controlling. | ||

|- | |||

| [[Cybernetic_Perspective | Cybernetic]] || Accounts for the first-order loop feedback, learning, and communication in addition to financial and production metrics. | |||

|- | |- | ||

| Holisitc || Extends from the cybernetic model with | | [[Holistic_Perspective | Holisitc]] || Holistic_Perspective | Extends from the cybernetic model with the second-order feedback loop and emphasizes the relationships and interactions between the organization’s different parts, including its culture, vision, mission, and reward systems. | ||

|} | |||

Regarding its conceptualization, several approaches have been proposed for categorizing performance depending on the context: research, societal, leadership, organizational development, etc.. For example, the models can be grouped into three categories based on their origins in economics, organizational, and social research<ref>Vibert C. (2004). Theories of macro organizational behavior: a handbook of ideas and explanations.</ref>. Others have suggested categorizing along the following three categories of objectives, systems, and stakeholders<ref>Campbell, J. P. (1977). On the nature of Organizational effectiveness. In P. S. Godman & J. M. Pennings (Eds.), New perspectives on organizational effectiveness. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Pp. 13-55.<br/>Zammuto, R. F. (1982). Assessing organizational effectiveness: Systems change, adaptation, and strategy. Albany, N.Y.:Suny-Albany Press.<br/>Quinn, R. E., Rohrbaugh, J. (1983). A Spatial Model of Effectiveness Criteria: Towards a Competing Values Approach to Organizational Analysis. Management Science. Vol. 29, No. 3, pp. 363-377.<br/>Cameron, K. S., Whetten, D. A. (1983). Organizational Effectiveness: One Model or Several? Preface. Orlando: Academic Press.</ref> which is the one we adopted here. The value model was analyzed separately from the stakeholders model because it offers a distinct general overall understanding of how individuals and organizations behave. The non-performance model was added, which stands apart and continues to be a powerful model for understanding and managing performance. This grouping enables highlighting different analytical anchor points, limitations, and relations with management control systems. | |||

{| class="wikitable" style="margin: auto;" | |||

|+ Performance Conceptualization | |||

! Models !! Focus | |||

|- | |||

| [[Performance_by_Objectives|Objectives]] || Objectives are set and managed at different levels of the organization. Techniques such as cost-benefit analysis, management by objectives, individual criteria, or behavioral goals are used. | |||

|- | |- | ||

| [[ | | [[Systems%27_Performance|Systems]] || Systemic models emphasize the importance of an organization's means, such as inputs, outputs, resource acquisition, and processes. They include the operations research model, the structural contingency model, and the culturalist and social regulation models. | ||

|- | |- | ||

| [[ | | [[Stakeholders%27_Performance|Stakeholders]] || Stakeholders' performance models emphasize the expectations of individuals and interest groups that are either within or surrounding the organization. It includes the organizational development model, satisfaction, and expectancy models. | ||

|- | |- | ||

| [[ | | [[Performance_by_Values|Values]] || Value models extend from the stakeholder model to understand organizations based on individual values and preferences. The concept of values encompasses broad aspects of social behavior that, unlike others, can be described, measured, and shared. | ||

|- | |- | ||

| [[Non_Performance|Non-performance]] || It is easier, more precise, consensual, and beneficial to address performance issues by problems and faults rather than by skills and performance criteria. | |||

| [[Non_Performance|Non-performance]] || | |||

|} | |} | ||

Organizational performance models have grown over the years, not to supplant previous models but rather to refine them, better understand their scope, and create new models that better fit their times. Since the 2000s, with the Internet, and more recently with AI, our capacity to collect and analyze people's data has grown to incredible levels, and so has the capacity of management control systems, and our potential to better understand and manage people. How organizations can better perform over time remains a question tied to how people can better perform individually and in teams. | |||

=Individual Performance= | |||

[[File:Performance_Individual.png|right|300px]] | |||

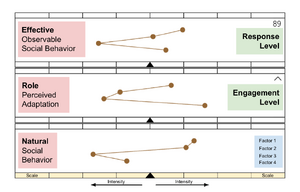

As the conceptualization of organizational performance and management control systems has dramatically progressed over the past decades, so has the understanding of people and their management. Although it takes more time than in technology, research in the social sciences has had the opportunity to build, break, challenge, and test the limits of many models and techniques. Adaptive profiles emerged from research in the 1950s in the USA and gradually began to penetrate organizations of all sizes worldwide. | |||

<blockquote>'''Adaptive profiles measure how people perform in context, their social behavior, adaptation efforts, and engagement.'''</blockquote> | |||

Just like with sports teams, people assume different roles in organizations and perform in various ways, influenced not only by their individual characteristics but also by how they interact and collaborate. How does individual performance on the field actually occur, and what results does it generate? The adaptive profiles provide some clues. Only when taken at a team level will it provide practical answers (see below)<ref>See more information [[Operationalizing_Performance|here on how adaptive profiles are used to operationalize performance at an individual level.]]</ref>. | |||

For instance, in rowing, in boats of eight, each rower assumes a different role, depending on their strengths and experience. The coxswain stirs the boat, motivates the rowers, and executes the race plan. The stroke seat (Seat 8) next to the coxswain sets the rhythm for the entire boat. Seat 7 perfectly mimics the stroke’s rhythm to pass it back to the other rowers. Seats 6 to 3 located in the middle of the boat provide pure power and speed. The bow pair (Seats 2 & 1) is responsible for balancing (or "setting") the boat. The eight rowers must row in sync under the direction of their coxswain, the boat’s captain<ref>I more often refer to rowing since this is the sport I have been exposed to most often, and also because rowing is an example of sports that requires exceptional cohesion during the race and after. All other team sports follow the same principles discussed and could be used as examples.</ref>. How the nine crew members perform individually from a social behavior standpoint, adapt, and engage is informed by their adaptive profiles. | |||

[[File:Profile Detailed.png|right|300px]] | |||

Adaptive profiles, like the one on the right, are constructed using a two-question adjective-format assessment. This method improves objectivity by applying statistical techniques and reducing key biases. The results are profiles that clearly and subtly show how people behave, feel, and think. They also provide insights about people's adaptation and engagement, the conditions to prevent underperformance, and the ways to maximize individual performance. At GRI, we have continued to study these profiles and expanded their use to enhance organizational performance<ref>The adaptive profiles are discussed [[Adaptive Profile|with greater detail in other articles on this wiki]].</ref>. | |||

Today, markets are familiar with techniques that measure traits and types. These techniques have been widely used in recruitment and coaching. Adaptive profiles, however, are more recent. They are based on factors. They differ in their characteristics from those of other techniques. They help rethink and improve individual assessments in ways that other approaches cannot; a major limitation of those techniques is how measures are represented, learned, and applied. Adaptive profiles provide greater precision and additional benefits across many applications in recruitment, management, leadership, and organizational development.<ref>See more [[Assessments_Potential_Uses | here in this wiki about the various potential uses of assessment techniques.]]</ref>. | |||

=Organizational Performance= | =Organizational Performance= | ||

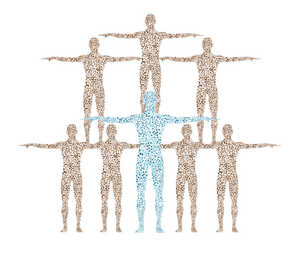

[[File: | [[File:Performance_Group.png|right|300px]] | ||

Adaptive profiles, | |||

Adaptive profiles are also used at the position, team, company, and even industry and societal levels, to represent the performance expected for jobs and for small- to large-group activities. | |||

Working with social behavior at the organizational level is especially useful and practical. Behaviors are observable. We can describe, analyse, and discuss them more effectively than when working with abstract concepts that can only be inferred rather than observed. As evidenced by performance models based on values<ref>See for more information [[Performance by Values | here in this wiki about increasing value-based performance.]]</ref>, working on social behavior applies universally to a variety of situations, stakeholders, industries, and cultures. | |||

==Social Performance== | |||

<blockquote>'''By aggregating adaptive profiles, we can analyse a group's social performance.'''</blockquote> | |||

An organization and team’s success relies not only on each individual's participation but also on their ability to focus their collective efforts. The team’s captain plays a vital role in building group cohesion, increasing team member involvement, and maintaining high levels of engagement. But how do these performances on the field actually occur, and what results do they generate? The adaptive profiles can explain that<ref> See in this article [[Organizational_Performance_Measurement#Social_Performance_Indicators| here on how social performance indicators are calculated based on the adaptive profiles]].</ref>. | |||

In the example of rowers above, the trust and cohesion built during training will be critical to success. Disengagement of one rower will impact the rest of the team. The coxswain often assumes the role of captain. During the race, they provide real-time calls and directions to the crew. However, other rowers may take a leadership role in the crew. The boat’s performance depends on the social performance of its nine members, as well as on support from coaches, staff, families, and educators who are directly or indirectly involved in the success. | |||

==Strategic Performance== | |||

<blockquote>'''Strategic performance, from a social behavior standpoint, can be established to determine how success will be achieved.'''</blockquote> | |||

As with other characteristics of experience and skills, some social behaviors are expected in positions that can be strategic. The adaptive profiles enable the modeling of expected behaviors in jobs and comparing their occurrence over time for individuals in those positions. Does performance occur at the group level as intended, with appropriate fit among people and with enough diversity? The answer can be provided by comparing the adaptive profiles of individuals, positions, teams, and organizations. Once a company's management has defined the behaviors expected in positions and teams, aggregating profiles and calculating strategic indicators based on them will formalize the intent and help manage performance gaps over time<ref> See in this article, [[Organizational_Performance_Measurement#Strategic_Performance_Indicators| here on how strategic performance indicators are calculated based on the adaptive profiles]].</ref>. | |||

Discussing these behaviors at the team and organizational levels increases the likelihood of reaching consensus on them. If social behaviors must be expressed differently across jobs and teams at varying levels of intensity and frequency, recruitment and management must ensure this. | |||

In our example of rowers, different social behaviors are expected of coxswains and rowers during the race. When training and socializing, athletes are expected to exhibit other social behaviors. How does their profile match what’s expected of them during race and outside of race time? Once aggregated, the adaptive profiles will provide the answer. | |||

[[File:Performance_Models_Full.png|right|400px]] | |||

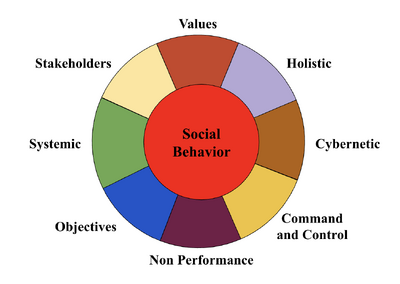

==Social Behavior Across Other Forms of Performance== | |||

As illustrated on the right, a more nuanced understanding of social behavior provides insights into other performance models, including how they are discussed, implemented, and complement one another. Whether a company deploys command-and-control, cybernetic, or holistic management control systems, its approach to performance analysis and management will be informed by the adaptive profiles. This is summarized in the table below. | |||

By comparing management intent with individuals’ adaptive profiles (measuring which social behaviors are present vs. absent), organizations can move beyond intuition and ensure their strategic focus—whether systemic, cybernetic, holistic, or values-based—is informed by a rigorous, data-driven understanding of their most central asset: their people. | |||

{| class="wikitable" style="margin: auto;" | |||

|+ Performance from a Social Behavior Standpoint | |||

! Models !! Insights from Adaptive Profiles | |||

|- | |||

| Objectives || Where objectives are managed by techniques like Management by Objectives (MBO) and behavioral goals, the adaptive profile provides the individual criteria for assessing how the person will set, communicate, and meet those goals. | |||

|- | |||

| Systems || These models emphasize organizational means (inputs, processes, outputs). The adaptive profile provides a critical input metric—the human factor—that affects processes (collaboration) and outputs (results). | |||

|- | |||

| Stakeholders || These models focus on the expectations of internal and external interest groups. The adaptive profile provides an understanding of the individual and group values and behaviors that drive the satisfaction and expectations of these stakeholders. | |||

|- | |||

| Values || This is the model the adaptive profile most directly informs, as it extends the stakeholder model by understanding organizations based on individual values and preferences—which are expressed through social behavior. The adaptive profile provides a system to describe, measure, and share these values across the organization. | |||

|- | |||

| Non-performance || This model suggests it is often easier to address performance by focusing on problems and faults rather than skills and criteria. The adaptive profile aids this by clearly identifying conditions to prevent underperformance (e.g., high adaptation effort and disengagement) and providing a precise language (observable behavior) for problem resolution. | |||

|} | |||

=Notes= | =Notes= | ||

Latest revision as of 07:00, 14 January 2026

Introduction

This article discusses various models of organizational performance that have been studied over the past decades, and the trend toward a better understanding of how individuals function and perform in groups, which is essential to other forms of performance.

When accurately measured and condensed into adaptive profiles applicable across a wide range of topics related to a company’s strategy and daily operations, these measures provide a new foundation for improving organizational performance.

Performance Models

Organizational performance can be approached through various models, which address aspects of its measurement and control on the one hand, and its conceptualization on the other.

Until the 1980s, management control research had focused on performance measures within the cybernetic model, an extension of the more popular command-and-control model that had dominated until the 1950s. Considering new individual and cultural factors alongside non-financial measures has enabled the holistic model to gradually overcome some limitations of the cybernetic model[1]. Since the 2000s, thanks to capabilities from software platforms, the Internet, and later AI, Management Control System (MCS) packages have integrated and powered management control systems as an integral part of managing organizations, most often aligned with holistic models. The three grand models are summarized in this table and detailed in separate articles.

| Models | Focus |

|---|---|

| Command and Control | Traditional hierarchical top-down approach, with original management control systems for planning and controlling. |

| Cybernetic | Accounts for the first-order loop feedback, learning, and communication in addition to financial and production metrics. |

| Holisitc | Extends from the cybernetic model with the second-order feedback loop and emphasizes the relationships and interactions between the organization’s different parts, including its culture, vision, mission, and reward systems. |

Regarding its conceptualization, several approaches have been proposed for categorizing performance depending on the context: research, societal, leadership, organizational development, etc.. For example, the models can be grouped into three categories based on their origins in economics, organizational, and social research[2]. Others have suggested categorizing along the following three categories of objectives, systems, and stakeholders[3] which is the one we adopted here. The value model was analyzed separately from the stakeholders model because it offers a distinct general overall understanding of how individuals and organizations behave. The non-performance model was added, which stands apart and continues to be a powerful model for understanding and managing performance. This grouping enables highlighting different analytical anchor points, limitations, and relations with management control systems.

| Models | Focus |

|---|---|

| Objectives | Objectives are set and managed at different levels of the organization. Techniques such as cost-benefit analysis, management by objectives, individual criteria, or behavioral goals are used. |

| Systems | Systemic models emphasize the importance of an organization's means, such as inputs, outputs, resource acquisition, and processes. They include the operations research model, the structural contingency model, and the culturalist and social regulation models. |

| Stakeholders | Stakeholders' performance models emphasize the expectations of individuals and interest groups that are either within or surrounding the organization. It includes the organizational development model, satisfaction, and expectancy models. |

| Values | Value models extend from the stakeholder model to understand organizations based on individual values and preferences. The concept of values encompasses broad aspects of social behavior that, unlike others, can be described, measured, and shared. |

| Non-performance | It is easier, more precise, consensual, and beneficial to address performance issues by problems and faults rather than by skills and performance criteria. |

Organizational performance models have grown over the years, not to supplant previous models but rather to refine them, better understand their scope, and create new models that better fit their times. Since the 2000s, with the Internet, and more recently with AI, our capacity to collect and analyze people's data has grown to incredible levels, and so has the capacity of management control systems, and our potential to better understand and manage people. How organizations can better perform over time remains a question tied to how people can better perform individually and in teams.

Individual Performance

As the conceptualization of organizational performance and management control systems has dramatically progressed over the past decades, so has the understanding of people and their management. Although it takes more time than in technology, research in the social sciences has had the opportunity to build, break, challenge, and test the limits of many models and techniques. Adaptive profiles emerged from research in the 1950s in the USA and gradually began to penetrate organizations of all sizes worldwide.

Adaptive profiles measure how people perform in context, their social behavior, adaptation efforts, and engagement.

Just like with sports teams, people assume different roles in organizations and perform in various ways, influenced not only by their individual characteristics but also by how they interact and collaborate. How does individual performance on the field actually occur, and what results does it generate? The adaptive profiles provide some clues. Only when taken at a team level will it provide practical answers (see below)[4].

For instance, in rowing, in boats of eight, each rower assumes a different role, depending on their strengths and experience. The coxswain stirs the boat, motivates the rowers, and executes the race plan. The stroke seat (Seat 8) next to the coxswain sets the rhythm for the entire boat. Seat 7 perfectly mimics the stroke’s rhythm to pass it back to the other rowers. Seats 6 to 3 located in the middle of the boat provide pure power and speed. The bow pair (Seats 2 & 1) is responsible for balancing (or "setting") the boat. The eight rowers must row in sync under the direction of their coxswain, the boat’s captain[5]. How the nine crew members perform individually from a social behavior standpoint, adapt, and engage is informed by their adaptive profiles.

Adaptive profiles, like the one on the right, are constructed using a two-question adjective-format assessment. This method improves objectivity by applying statistical techniques and reducing key biases. The results are profiles that clearly and subtly show how people behave, feel, and think. They also provide insights about people's adaptation and engagement, the conditions to prevent underperformance, and the ways to maximize individual performance. At GRI, we have continued to study these profiles and expanded their use to enhance organizational performance[6].

Today, markets are familiar with techniques that measure traits and types. These techniques have been widely used in recruitment and coaching. Adaptive profiles, however, are more recent. They are based on factors. They differ in their characteristics from those of other techniques. They help rethink and improve individual assessments in ways that other approaches cannot; a major limitation of those techniques is how measures are represented, learned, and applied. Adaptive profiles provide greater precision and additional benefits across many applications in recruitment, management, leadership, and organizational development.[7].

Organizational Performance

Adaptive profiles are also used at the position, team, company, and even industry and societal levels, to represent the performance expected for jobs and for small- to large-group activities. Working with social behavior at the organizational level is especially useful and practical. Behaviors are observable. We can describe, analyse, and discuss them more effectively than when working with abstract concepts that can only be inferred rather than observed. As evidenced by performance models based on values[8], working on social behavior applies universally to a variety of situations, stakeholders, industries, and cultures.

Social Performance

By aggregating adaptive profiles, we can analyse a group's social performance.

An organization and team’s success relies not only on each individual's participation but also on their ability to focus their collective efforts. The team’s captain plays a vital role in building group cohesion, increasing team member involvement, and maintaining high levels of engagement. But how do these performances on the field actually occur, and what results do they generate? The adaptive profiles can explain that[9].

In the example of rowers above, the trust and cohesion built during training will be critical to success. Disengagement of one rower will impact the rest of the team. The coxswain often assumes the role of captain. During the race, they provide real-time calls and directions to the crew. However, other rowers may take a leadership role in the crew. The boat’s performance depends on the social performance of its nine members, as well as on support from coaches, staff, families, and educators who are directly or indirectly involved in the success.

Strategic Performance

Strategic performance, from a social behavior standpoint, can be established to determine how success will be achieved.

As with other characteristics of experience and skills, some social behaviors are expected in positions that can be strategic. The adaptive profiles enable the modeling of expected behaviors in jobs and comparing their occurrence over time for individuals in those positions. Does performance occur at the group level as intended, with appropriate fit among people and with enough diversity? The answer can be provided by comparing the adaptive profiles of individuals, positions, teams, and organizations. Once a company's management has defined the behaviors expected in positions and teams, aggregating profiles and calculating strategic indicators based on them will formalize the intent and help manage performance gaps over time[10].

Discussing these behaviors at the team and organizational levels increases the likelihood of reaching consensus on them. If social behaviors must be expressed differently across jobs and teams at varying levels of intensity and frequency, recruitment and management must ensure this.

In our example of rowers, different social behaviors are expected of coxswains and rowers during the race. When training and socializing, athletes are expected to exhibit other social behaviors. How does their profile match what’s expected of them during race and outside of race time? Once aggregated, the adaptive profiles will provide the answer.

Social Behavior Across Other Forms of Performance

As illustrated on the right, a more nuanced understanding of social behavior provides insights into other performance models, including how they are discussed, implemented, and complement one another. Whether a company deploys command-and-control, cybernetic, or holistic management control systems, its approach to performance analysis and management will be informed by the adaptive profiles. This is summarized in the table below.

By comparing management intent with individuals’ adaptive profiles (measuring which social behaviors are present vs. absent), organizations can move beyond intuition and ensure their strategic focus—whether systemic, cybernetic, holistic, or values-based—is informed by a rigorous, data-driven understanding of their most central asset: their people.

| Models | Insights from Adaptive Profiles |

|---|---|

| Objectives | Where objectives are managed by techniques like Management by Objectives (MBO) and behavioral goals, the adaptive profile provides the individual criteria for assessing how the person will set, communicate, and meet those goals. |

| Systems | These models emphasize organizational means (inputs, processes, outputs). The adaptive profile provides a critical input metric—the human factor—that affects processes (collaboration) and outputs (results). |

| Stakeholders | These models focus on the expectations of internal and external interest groups. The adaptive profile provides an understanding of the individual and group values and behaviors that drive the satisfaction and expectations of these stakeholders. |

| Values | This is the model the adaptive profile most directly informs, as it extends the stakeholder model by understanding organizations based on individual values and preferences—which are expressed through social behavior. The adaptive profile provides a system to describe, measure, and share these values across the organization. |

| Non-performance | This model suggests it is often easier to address performance by focusing on problems and faults rather than skills and criteria. The adaptive profile aids this by clearly identifying conditions to prevent underperformance (e.g., high adaptation effort and disengagement) and providing a precise language (observable behavior) for problem resolution. |

Notes

- ↑ Henri, J. F. (2004). Performance measurement and Organizational Effectiveness: Bridging the gap. Managerial Finance. Vol. 30, No. 6, pp 93-123.

- ↑ Vibert C. (2004). Theories of macro organizational behavior: a handbook of ideas and explanations.

- ↑ Campbell, J. P. (1977). On the nature of Organizational effectiveness. In P. S. Godman & J. M. Pennings (Eds.), New perspectives on organizational effectiveness. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Pp. 13-55.

Zammuto, R. F. (1982). Assessing organizational effectiveness: Systems change, adaptation, and strategy. Albany, N.Y.:Suny-Albany Press.

Quinn, R. E., Rohrbaugh, J. (1983). A Spatial Model of Effectiveness Criteria: Towards a Competing Values Approach to Organizational Analysis. Management Science. Vol. 29, No. 3, pp. 363-377.

Cameron, K. S., Whetten, D. A. (1983). Organizational Effectiveness: One Model or Several? Preface. Orlando: Academic Press. - ↑ See more information here on how adaptive profiles are used to operationalize performance at an individual level.

- ↑ I more often refer to rowing since this is the sport I have been exposed to most often, and also because rowing is an example of sports that requires exceptional cohesion during the race and after. All other team sports follow the same principles discussed and could be used as examples.

- ↑ The adaptive profiles are discussed with greater detail in other articles on this wiki.

- ↑ See more here in this wiki about the various potential uses of assessment techniques.

- ↑ See for more information here in this wiki about increasing value-based performance.

- ↑ See in this article here on how social performance indicators are calculated based on the adaptive profiles.

- ↑ See in this article, here on how strategic performance indicators are calculated based on the adaptive profiles.